Usenet is a global distributed discussion system. Prior to the world wide web, it served as an early message board and forum. These days, it’s primarily used for file sharing.

The content on Usenet consists of two types of files: text and binary. If you’re reading this, you’re probably more interested in the latter. Binary files include audio, video, software and other large files. A Usenet service connects the user to multiple Usenet servers from which they can download files. The files are indexed in a .NZB format, which allow the user to download and compile all the pieces of a file, known as articles, from multiple servers.

You can subscribe to a Usenet provider that hosts files for a monthly or yearly fee. These providers have varying levels of retention, which is the amount of time an article posted to Usenet is stored on the provider’s servers before deletion. More retention means access to more files, which generally means better search results and more complete file downloads.

The subscriber can use the service to search for an NZB file, which is similar to a torrent file. That allows you to download files from your Usenet provider’s servers to a personal computer through a “newsreader” app.

If you’re just looking for a quick recommendation, here’s a summary of the best Usenet providers in 2025:

- Newshosting Our top recommendation. Fastest downloads and best retention rates. Newsreader app with search included.

- UsenetServer Unlimited downloads, fast speeds, and long retention rates.

- Easynews High speeds and comes with a great search feature.

- Giganews Good all-round service for a low price.

Best Usenet providers of 2025

Looking to get started with Usenet? We reviewed the top Usenet providers based on the following criteria:

- File retention

- Security and privacy

- Download speed

- Data and connection limits

- App and service quality

- Customer support

Here are our most recommended Usenet providers for 2025:

1. Newshosting

Newshosting is a complete service that includes everything you need to get started with Usenet. The Newshosting app includes an indexer (for searching) and newsreader (for downloading). It boasts industry-best data retention and completion rates, so you have the best chance of finding what you’re looking for.

You can opt to download through an encrypted connection to keep your Usenet activity private. Newshosting keeps zero download logs to maintain users’ privacy.

Plans are available in three tiers. The second tier removes the 50GB per month limit and increases the number of connections from 30 to 100. The top tier adds in a VPN.

BEST USENET PROVIDER:Newshosting stands out as a premium, all-inclusive Usenet service and app, and you can try before you buy with a generous 30GB, 14-day free trial.

Read our full Newshosting review.

2. UsenetServer

For Usenet veterans, we recommend UsenetServer. It doesn’t come with a newsreader app like Newshosting, but long-time users typically prefer their own setups anyway. What it does have is a low price, high speeds, unlimited downloads, and high retention and completion rates.

All plans include SSL-encrypted downloads. You can use up to 20 SSL connections at a time. UsenetServer doesn’t store any download logs.

Plans are available for one, three, and 12 month terms. A VPN is included with the annual plan.

BUDGET USENET:UsenetServer is a no-frills provider with cheap plans, unlimited downloads, and fast speeds. Take advantage of the 10GB, two-week free trial.

Read our full UsenetServer review.

3. Easynews

Easynews lets users download files through their normal web browsers thanks to its handy web app and HTTP server. That means you don’t have to bother with third-party indexers or news readers if you don’t want to. Whether you use HTTP or opt for a traditional NNTP news reader and index, downloads are encrypted with SSL. The provider doesn’t keep any download logs.

Easynews boasts high retention and up to 60 connections, which allows for very fast downloads. All plans have monthly data caps (20/40/150 GB), but unused data does roll over to the next month, and you can earn extra data through its loyalty program. The top-tier plan comes with a VPN.

USENET IN BROWSER:Easynews makes it simple to get started with Usenet thanks to its one-of-a-kind web app. You can get a 14-day trial with a 50GB download limit.

Read our full Easynews review.

4. Giganews

Giganews guarantees it will max out your download speeds. It also boasts 100 percent completion and uptime–guarantees that no other provider makes. To top it off, Giganews comes with 24/7 live support, something that many providers advertise but don’t actually deliver on.

Giganews makes its own Usenet browser, an app called Mimo, that you can use to search and download NZB files. A download accelerator is also available. Downloads are protected by SSL encryption, and VyprVPN is included with subscriptions for even better privacy.

You can subscribe for a month, six months, or one year, with bigger discounts for longer terms. There’s no other difference between the plans.

FAST AND COMPLETE:Giganews delivers on big promises when it comes to speed, uptime, and completion. A 10GB, 14-day free trial is on offer.

Read our full Giganews review.

An overview of Usenet

Long before Reddit and BitTorrent, there was Usenet. Think of it as the original online social network. Established in the early 1980s, Usenet was a cross between email and web forums used to exchange text files between users.

Fast forward to the 1990s, Usenet gets an upgrade to upload and share large binary files, such as videos, music, and images. But when BBS forums like Reddit and the BitTorrent protocol came around, Usenet was largely left behind.

This 36-year-old technology is far from dead, though, and remains one of the fastest and most secure platforms. So why haven’t you heard much about it?

In the past, users faced technical hurdles that many weren’t willing to overcome. They needed multiple pieces of software, in addition to a Usenet subscription, to get set up. Over time, though, Usenet providers and Usenet fans alike have developed simpler and much more powerful software, making it easier to get up and running.

Usenet vs. Torrents

Why would you pay for Usenet when you can just torrent? Several reasons. First, Usenet downloads are much, much faster, because they come from centralized servers instead of other people’s computers. Instead of peers, Usenet can connect to dozens of servers at a time, which means you can download at speeds as fast as your ISP can handle.

Secondly, Usenet is private. The connections take place between you and the provider’s servers, and most providers offer an SSL-encrypted connection. Some even throw in VPNs for good measure. Torrents, on the other hand, require you share at least some identifying information with fellow users in order to connect to the tracker and peers (e.g. your IP address).

Thirdly, downloading a Usenet file doesn’t mean you have to seed it for other users afterwards. Usenet file transfers are one-way only – from the centralized server directly to the client requesting articles from the server.

Usenet providers make files available for a certain number of days. This is called ‘retention.’ Retention rates vary widely from provider to provider. For example, a provider like Newshosting has over 18 years of retention on every article posted to Usenet. In other words, every article posted to Usenet over the last 18 years will be available on their servers. Torrents, on the other hand, only stay up as long as there are people seeding the file.

Retention rates are pretty much the same among all of the providers we recommend.

Security tip!

Most Usenet access comes with 256-bit SSL encryption, but we recommend you use a VPN for extra security. Yes, it may slow down your speeds a bit, but you do get peace of mind knowing all your traffic (not just Usenet), is being routed through an anonymous server. And if someone asks your Usenet provider what your IP address is, they won’t get your real one.

Factors to consider when choosing a Usenet provider

You can find a more detailed guide to all of our Usenet criteria here, but here are the main factors at-a-glance:

Retention period

This is the amount of time articles are stored on a provider’s servers and one of the most important things to look at when choosing a service. Retention determines how many articles you get access to, which then determines how good (or bad) your search results and download completion will be.

Always opt for the provider with the most retention. Also, make sure the same retention is available on all newsgroups and all articles. Some providers say ‘up to’ a stated number of days, meaning many articles are deleted from the servers before this, which allows them to trim down their server costs. Check the fine print.

Download Limits

If you want unlimited downloads, make sure your provider will give you exactly that. Some services actually put an undisclosed cap on your monthly allotment and pause your account for too much use.

Speed Limits

Similar to the above, some services will throttle your download speeds to a crawl after hitting a certain download threshold. The best providers do not cap downloads, nor do they throttle your download speeds.

Server Locations

The best services operate their own network with multiple server locations (usually in both North America and Europe). This ensures the best possible connection speeds no matter where you’re located.

What you need to start using Usenet

To get started with Usenet, you’ll require three things: a subscription to a provider, a newsreader client, and an indexer/search engine. Some providers wrap all three of these things into one tidy package. If that’s not the case, free newsreaders and indexers are available online.

We’ve got a guide to walk you through the full Usenet setup process here.

The history of Usenet

Today’s Usenet is almost unrecognizable compared to when it first established in 1980. Today, it’s a service for downloading videos and other digital media from other users, second only to BitTorrent. But it started out as a means for universities and experts in the field of technology to read and post messages in their community.

Usenet was a community for the brightest minds in tech. Prior to the proliferation of commercial internet to homes and businesses, many of the biggest advances in internet technology were first posted on Usenet. Tim Berners-Lee announced the launch of the World Wide Web in 1991. Linus Torvalds introduced the Linux Project in the same year. And in 1993, Marc Andreesen publicized the Mosaic browser, which popularized the World Wide Web and made it possible to add images to web pages. All of these advancements were first announced on Usenet.

This article will provide a layman-accessible chronology of the major developments in Usenet and its role alongside contemporaries, including ARPANET and the World Wide Web.

Related: A brief history of the internet

This article assumes you have at least some surface-level knowledge of Usenet and how it works. If this is your first time ever hearing of Usenet, we recommend you read our overview.

UUCP and A News

Jim Ellis and Tom Truscott first conceived of Usenet in 1979 while attending graduate school at Duke University. It was created to replace a BBS announcement program and create a connection with the nearby University of North Carolina. Its first 50 or so members came from a USENIX conference held at the University of Delaware in June 1980, where Duke’s Steve Daniel presented Usenet and invited attendees to join.

The first messages were sent via A News, the original program for reading and serving Usenet newsgroups. A News, then just known as “news”, expanded on Unix’s “message of the day” feature that allowed system operators to display messages to users when they logged in. A News took this and combined it with UUCP (Unix-to-Unix Copy), a then-new protocol that allowed for remote transfer of files and messages between computers.

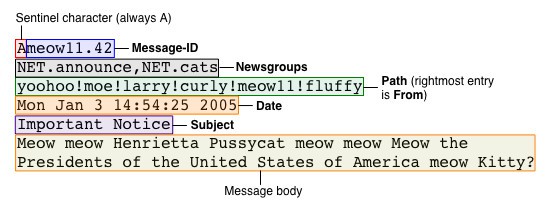

A News got its name because every message posted begins with the letter ‘A’ as a marker. Users read the messages right from the command line or when they logged in. They could add a message to be posted either on the local machine for other users to see when they logged in, or queue it to be sent over the entire network to anyone subscribed to a particular newsgroup. At first, Usenet was primarily used for making announcements, and the messages looked something like this:

Due to the bandwidth limitations of 1980s dial-up modems, A News was designed to be concise rather than robust. A News readers couldn’t respond over Usenet. Email responses were used instead. Users couldn’t skip messages, and posts weren’t threaded. The “path” noted in the image above shows the route that the message went through to arrive at its destination. “Bang paths” were very slow, sometimes taking up to a week to send news, and it was not uncommon for messages to be lost. These early iterations of email addresses were later superseded by the ‘@’ symbol we know today.

Bang paths are still used in Usenet messages today, but not for routing purposes.

By the end of its first year in operation, Usenet brought on 50 member sites, including Bell Labs and universities like Reed College and University of Oklahoma.

NNTP and B News

Around the same time that Usenet first surfaced, ARPANET started expanding access to other protocols including TCP/IP, forming the foundation for today’s internet and the World Wide Web. But it also granted access to other protocols as well, including the UUCP protocol used by Usenet. By 1983, thousands of people joined Usenet, and over 500 UUCP hosts disseminated content through the network.

A News was soon made obsolete in 1983 by its successor, B News. B News was faster and more reliable, allowing up to 50 articles to be posted per day instead of just one or two. It was invented by Berkeley student Mark Horton and high school student Matt Glickman.

By 1984, only one year later, the number of hosts nearly doubled to 940, and more than 100 different newsgroups were up and running.

In 1986, two University of California engineers created the NNTP protocol. NNTP is used specifically for transporting Usenet articles between news servers so end users can read and post news. This allowed newsreader applications to run on personal computers connected to local networks instead of the server itself. Today, NNTP is still used by the majority of Usenet servers. NNTP allows Usenet articles to be distributed using TCP/IP, which ARPANET also adopted.

The Great Renaming

As Usenet grew in popularity, the current structure by which newsgroups were organized didn’t scale so well. All newsgroups were categorized into one of three categories: *net. **for unmoderated discussions, *mod. **for moderated discussions, or *fa. **for groups gatewayed from ARPANET. NNTP and B News lifted some of the software restraints, making it practical to reorganize newsgroups.

The reformation was largely led by an informal group of large site administrators known as the backbone cabal. Started in 1983, this group made its news servers available 24 hours per day instead of the nighttime-only operations of their smaller counterparts. Usenet as a whole was decentralized and thus had no official leaders, but the backbone cabal acted as a respected authority in an otherwise chaotic community.

At the time, many doubted the existence of the cabal, but its influence allowed it to put forth the Great Renaming in 1987. This would fundamentally change the categories to comp.* (computers), misc.* (miscellaneous), news.* (Usenet and newsgroups), rec.* (recreation and entertainment), sci.* (science), soc.* (social), and talk.* (religion, politics, and other controversial subjects).

The new categories became known as the “Big Seven”, and they were open to everyone except for some of the moderated newsgroups within them. In 1995, after ISPs started offering Usenet access to the general public and Usenet became more mainstream among academics, .humanities* was added to the list, turning the Big Seven into the Big Eight. Under the new system, before any newsgroup could be created, the creator was required to submit a request for discussion (RFD) in the news.announce.newsgroups newsgroup. It was then considered in the news.groups.proposals newsgroup. Finally, the Big 8 Management Board (B8M8) had approved the proposal.

Not all of the old hierarchies were abolished; many such as the education-focused .k12* hierarchy remained in place.

Some speculated that the renaming took place to appease European networks that refused to pay for hosting high-volume but low-content newsgroups discussing controversial topics like religion and racism. These newsgroups were bundled together under .talk*. This made it easier for networks to exclude unwanted newsgroups from their Usenet servers. This did not sit well with many outspoken Usenet users who believed the Great Renaming would restrict their freedom of expression. Many topics were still off limits, including newsgroups about recreational drug use and sex.

Shortly after the Big Seven became the new status quo, another popular hierarchy was created: .alt* (alternative). Though it was never part of the Big Eight, .alt* became the go-to place for less academic and more extreme discussion that ISPs might not have tolerated in .talk*. It was free from the constraints and centralized control of the formal hierarchies in the Big Eight. Anyone could create an alt newsgroup. One popular FAQ on the subject joked that “alt” stood for Anarchists, Lunatics, and Terrorists. Today it is probably the most recognized hierarchy for the majority of Usenet users, largely thanks to the alt.binaries and alt.sex sections. More on those later.

The term “alt right” used to describe fringe groups with conservative ideologies did not originate on Usenet. The phrase’s mainstream adoption was likely accelerated, though, thanks to its familiarity among Usenet veterans who view it as an allusion to the conspiracy theorists and hate groups that congregated on Usenet long before 4Chan was ever conceived.

C News and InterNetNews

In 1987, University of Toronto staff members created the C News server package. They completely rewrote B News to make it faster and less buggy. C News continued to be used until the mid 1990s.

In 1991, C News was superseded by InterNetNews, another news server package that fully integrated NNTP functionality. INN is now the most commonly used server package and is still actively maintained.

ISPs join in

Until the 1990s, Usenet was the domain of colleges, universities, and tech research labs. Every fall, freshman undergraduates would get their first taste, resulting in an annual wave of new Usenet users. They would either learn to love Usenet or hate it, and the numbers would taper off for the remaining 11 months of the year.

Then, in September 1993, America Online (AOL) became the first major internet service provider to offer Usenet access to its users. Usenet became part of AOL’s larger marketing campaign to recruit new subscribers. This time, the numbers did not taper off, and Usenet became vastly more popular. The influx became known in the Usenet community as the “Eternal September.” Newsgroups sprung up in a similar fashion to today’s subreddits for every likeminded group of people tech savvy and patient enough to learn Usenet.

By the mid-90s, hosting Usenet servers became the norm for American ISPs, or they would at least offer subscribers an account with a third-party provider. Each host synchronized its content with everyone else, creating a uniform redundant network.

Usenet was still being used almost entirely for text-based interaction. Newsgroups were the precursors to today’s BBS forums (read: reddit), blogs, RSS feeds, and newsletters.

Sex and binaries

The .alt* hierarchy spawned a wide variety of newsgroups including those dedicated to specific celebrities and other aspects of pop culture. But the growth of two sections in particular around the mid-1990s signaled a paradigm shift that fundamentally changed Usenet forever, for better or worse.

A “binary” file refers to any non-text file. In the context of Usenet, binary typically refers to audiovisual media. With internet service providers like AOL now hosting Usenet files, the ability for the network to transmit large amounts of data became feasible. This, in combination with early proliferation of home broadband networks and internet-connected home computers, kicked off Usenet’s transformation from a news and discussion aggregator to a file sharing network.

Alt.sex and alt.binaries later became the two most popular sections of Usenet. By October 1993, 8 percent of all Usenet users–3.3 million people–read news from alt.sex. Newsgroups posted pictures ranging from Playboy-style nudes to more niche fetishes and generally some pretty kinky stuff.

New programs allowed binary files to be encoded in a Usenet-compatible way, making it more practical to distribute binary files. Files on Usenet often limit the amount of characters allowed in a post. To get around this limitation, new programs split up binary files into multiple smaller files that are later reassembled by the newsreader. In 2001, the yEnc file encoding was introduced, which cut data transfers down by 30 percent. Today’s Usenet users will no doubt recognize the encoding that’s now commonplace on binary files.

Alt.binaries distributed a wide range of other content but was particularly known for binary posts, which generally consist of multimedia like larger-format audio, video and software files. Even though bandwidth and server space were growing rapidly, Usenet hosts struggled to keep up with the large volume of data being uploaded and downloaded from their servers. Thus, binary retention limits were introduced, which would remove files after they reach a certain age to make room for new files.

Years before BitTorrent was invented, Usenet evolved from a platform for text discussion to the world’s most popular file sharing network.

Decline

By the mid- to late-1990s, Usenet reached a turning point that many of its most fervent users agreed marked the beginning of a long decline. Those who remember it cite a few different reasons, but it was probably a combination of factors that led a once-burgeoning technology into relative obscurity.

The growth in active users peaked and started to drop off, but the costs of operating the network continued to increase due to the influx large binary files. When internet service providers realized that their subscribers could do without Usenet, they began cutting binary retention times and eventually Usenet access altogether. Abandoning Usenet was a win-win for ISPs that didn’t want to keep up with the money and resource-intensive investments required to maintain Usenet server infrastructure.

Another popular theory is that Usenet simply lost out to the World Wide Web. For a while, they were competing standards. Mosaic and Netscape browsers offered laymen a far easier and graphically pleasing medium to access content on the internet. Usenet stubbornly stood by its text-based interface, with no such graphical user interface ever taking hold among the larger community. As it turns out, command lines aren’t for everyone.

Usenet and NNTP have no identity authentication mechanism. This made it extremely difficult to root out spam, phishing scams, malware, forged headers, and general abuse.

In 2010, Duke University–Usenet’s birthplace–decommissioned its Usenet server, citing high costs and low usage.

Independent news services

As alt.binaries grew in popularity, independent news services began cropping up to meet demand from users. These offered and continue to offer high quality service, fast downloads, and much longer retention times than those offered by ISPs. These include premium Usenet providers that still operate today, including Newshosting and UsenetServer, among others.

When ISPs and universities started to jump ship, these services grew to fill in the gap. Unlike traditional hosts that offered Usenet access as part of a larger package, independent Usenet providers focused solely on Usenet. They give users access to the entire network, but most people use them to download files from alt.binaries and other file sharing sections of the alt hierarchy.

By the mid-2000s, independent Usenet providers were the most popular means of accessing Usenet. But it was a win by default; ISPs and universities wanted nothing to do with it anymore.

Premium Usenet providers continued to up their game with bespoke newsreader clients, private encrypted access, and ever-growing retention times.

Usenet today

Usenet is still alive and active today, and the software applications and interfaces have vastly improved. A handful of active discussion groups are still going strong, but most many Usenet subscribers are drawn by the speed and efficiency of binary file downloads.

The average daily volume of data transferred on Usenet is actually higher than ever, according to now-shuttered provider Altopia. Usenet doesn’t have more users or active newsgroups, however. The increase consists of more and larger binary files being uploaded and downloaded, plus a huge amount of automated spam.

An archive of non-binary Usenet posts back to 1981 is available on Google Groups. Deja News began archiving Usenet posts in 1995, creating a huge, searchable database. Google acquired the database in 2001, then added pre-1995 posts that were donated from a handful of universities and companies. Google continues to archive Usenet posts and provide a shared gateway to them, but some have criticized Google Groups, somewhat ironically, for its poor search functionality.

Altopia reported in 2020 that Usenet users post 76.4TB of daily volume, but it’s unclear how much of that is spam. The total number of newsgroups now stands at about 120,000, but only an estimated 20,000 are considered active.

After a long and fascinating history, Usenet lives on. And as the World Wide Web becomes more fragmented and centralized by major corporations, some still see in Usenet the only true decentralized, free, and open internet made by users, for users.

- Read more Usenet FAQs