What is WebDAV? In what contexts do you encounter it? How does it differ from its alternatives?

WebDAV is a long-standing protocol that enables a webserver to act as a fileserver and support collaborative authoring of content on the web. Though being supplanted by more modern mechanisms, it’s still a reliable workhorse encountered in many different servers, clients, and apps.

The web and WebDAV

The world-wide-web was intended to be a medium for consuming and producing content. But web-browsers almost immediately lost their ability to edit webpages, and read-only content ballooned to become the overwhelming norm.

WebDAV (Web Distributed Authoring and Versioning) was created in the late 1990s by a working group of the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF), led by Jim Whitehead. Its primary goal was to extend HTTP to support collaborative web content editing and file management. At the time, the web was evolving from a platform for static content to a more dynamic and interactive environment. WebDAV addressed the need for a protocol that enabled remote users to collaboratively edit and manage files on a web server.

The protocol was designed to facilitate web-based content authoring, making it easier for teams to collaborate on shared documents, manage version control, and maintain consistent file structures. It became a foundation for various applications, including content management systems, collaborative editing tools, and network file systems like Microsoft’s Web Folders and Apple’s iDisk.

While it provides a standard for file management over HTTP, varying levels of support for key features like locking, versioning, and namespace extensions can create compatibility issues. Some clients may fail to fully implement the protocol or may handle HTTP methods differently, leading to inconsistencies in file synchronization, permissions, or user experience. This fragmentation creates compatibility challenges across different tools. As a protocol, WebDAV is a guideline, not a software spec, so variations in implementation emerged.

What is WebDAV?

WebDAV (RFC 4918) is an extension to HTTP, the internet protocol that web-browsers and webservers use to communicate with each other. The WebDAV protocol enables a webserver to behave like a fileserver too, supporting collaborative authoring of web content.

WebDAV extends the set of standard HTTP methods and headers to provide the ability to create a file or folder, edit a file in place, copy or move or delete a file, etc. As an extension to HTTP, WebDAV normally uses port 80 for unencrypted access and port 443 (HTTPS) for secure access.

To support collaborative authoring, the original specification of WebDAV included file locking, but it punted on the “versioning” part of DAV due to the complexity of the revision tracking domain. DeltaV (RFC 3253), the versioning and configuration management piece of WebDAV, was defined later. Searching capabilities were also added in a later extension (RFC 5323).

File access and manipulation is a well-understood capability that’s useful to a wide audience. But revision tracking is foreign to nontechnical users. There’s also no common method that operating systems, version control systems, and applications use to model history and change. Many schemes are in use. As a consequence, WebDAV without versioning is widespread, and DeltaV is much less widely implemented.

If you encounter a WebDAV server referred to as “class 1”, that means it lacks locking. Class 2 includes locking. A WebDAV server with versioning is often just called a “DeltaV” server.

WebDAV has itself been the basis for additional protocols, including calendaring (CalDAV) and contact management (CardDAV).

Where you’ll find WebDAV

WebDAV turns up in many different contexts, on the server or client-side.

One warning: many of these have had WebDAV support for quite a while. When WebDAV is not central to the particular package, the WebDAV functionality may not be maintained as well as it once was.

WebDAV servers

A WebDAV server is always a web server, but it may be embedded in another system.

- General-purpose webservers The default open-source WebDAV implementation is in the Apache HTTP Server. Many web servers support WebDAV via an add-on module, such as Nginx, lighttpd, and Microsoft IIS.

- Version control systems Several version control systems are accessible via some form of WebDAV, including Subversion, Git, and PVCS.

- Collaborative Platforms and Content Management Systems Collaboration platforms like Microsoft Sharepoint, or CMSs like WordPress, Drupal, or Joomla may have WebDAV built-in or available via add-on modules.

- Network-Attached Storage and Cloud storage services Network-Attached Storage (NAS) devices on your LAN may support remote access via WebDAV.

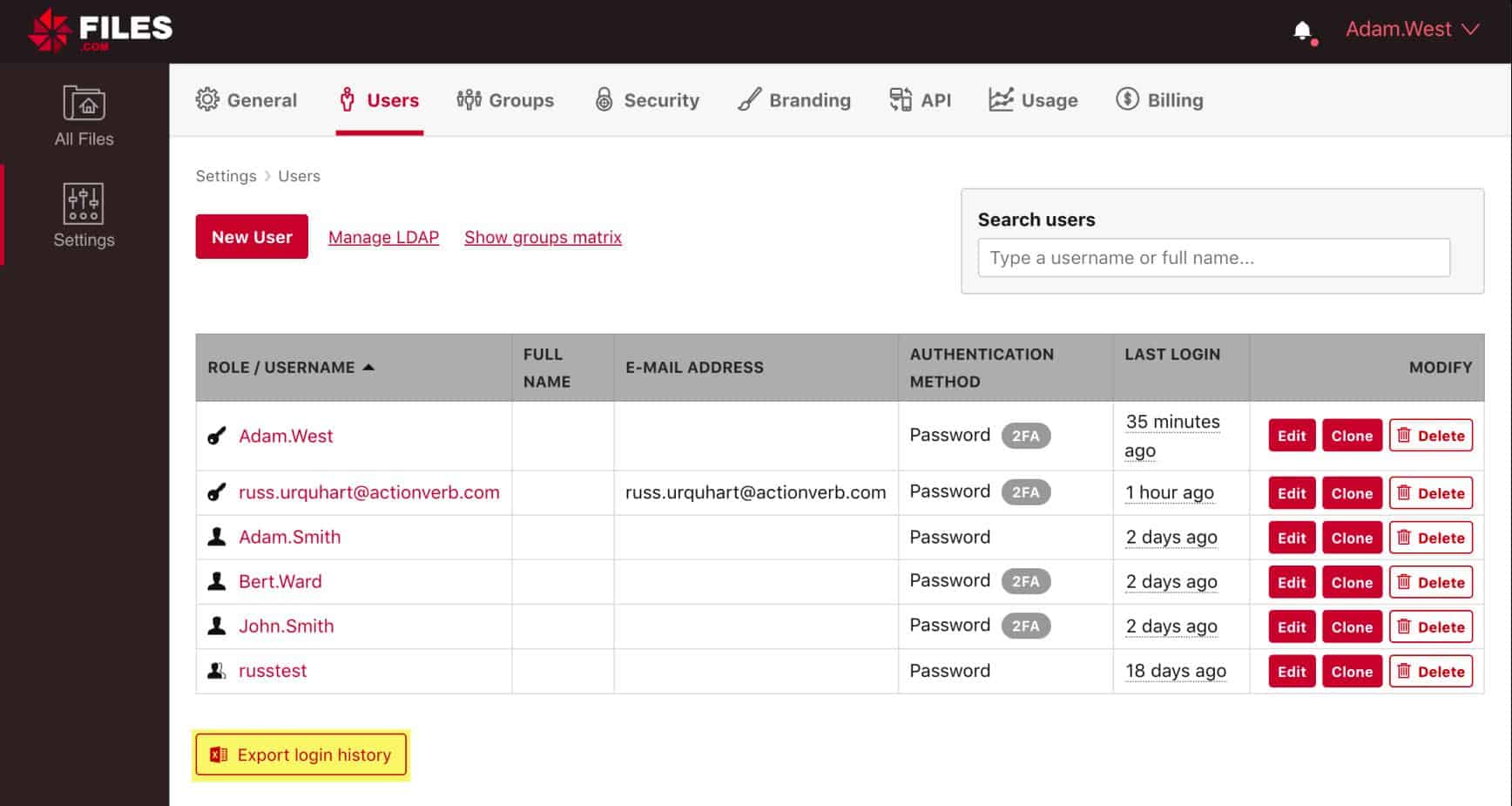

Files.com (FREE TRIAL)

Cloud file hosting services, such as Files.com usually allow access to rented file space directly from on-premises desktops through WebDAV. The Files.com system also acts as a collaborative file sharing space and a safe way to send files, by uploading to the file server and sending links to them instead of the actual files.

The Files.com service can be depicted on a local computer running Windows, Mac OS, or Linux simply by setting up a permanent connection to the account file space as a network drive. This process uses WebDAV. Once the network drive has been set up, users just need to drag and drop files to it in order to upload them to the Files.com storage space. Start a 7-day free trial.

- Various applications WebDAV turns up in random places where remote file manipulation and editing is useful. For instance, the system-design platform LabView can use WebDAV for transferring files to/from an embedded target computer.

WebDAV clients

As the Subversion documentation notes, WebDAV clients are standalone applications, extensions to file explorers or filesystem modules. Specifically, a WebDAV client may be one of the following.

WebDAV file-access apps

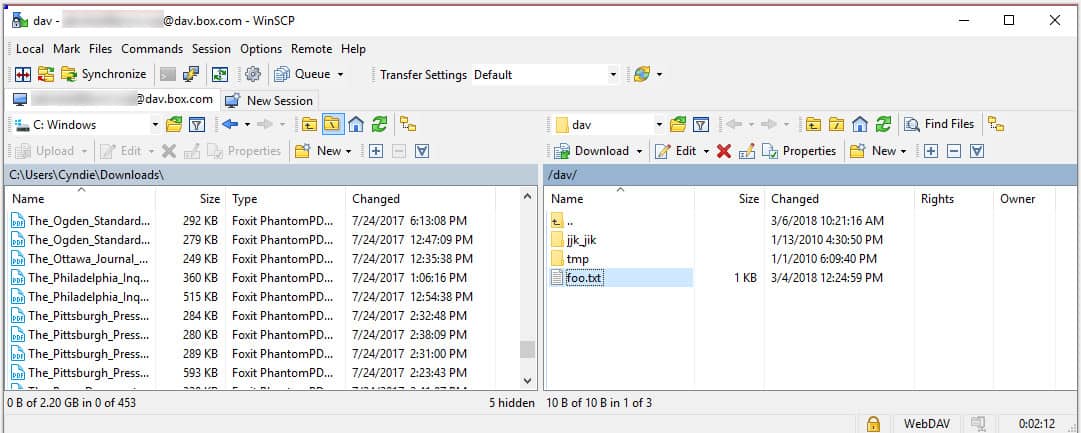

Apps aimed at giving you access to remote files may be purely WebDAV oriented, like the Linux command-line tool cadaver, or the graphical DAV Explorer. Or they may be tools that speak multiple protocols, like WinSCP or Cyberduck.

These let you download and upload files, manipulate folders, etc; the GUI ones provide drag-and-drop and related visual metaphors.

Apps that use WebDAV

A range of applications have the ability to work with files accessed via WebDAV. The application’s file selection dialog supports entering not just a local filename, but a WebDAV URL, with the username and password needed for the WebDAV server. These applications include Microsoft Office (Word, Excel, etc); Apple iWork (Pages, Numbers, Keynote); Adobe Photoshop and Dreamweaver; and others.

When such an app works with files or folders on a WebDAV server, WebDAV is working behind the scenes to provide collaborative remote file modifications. The files on the server are edited “in place”, without downloading to the local filesystem for later re-uploading (which creates multiple copies that can get out of sync.)

File-explorer extensions

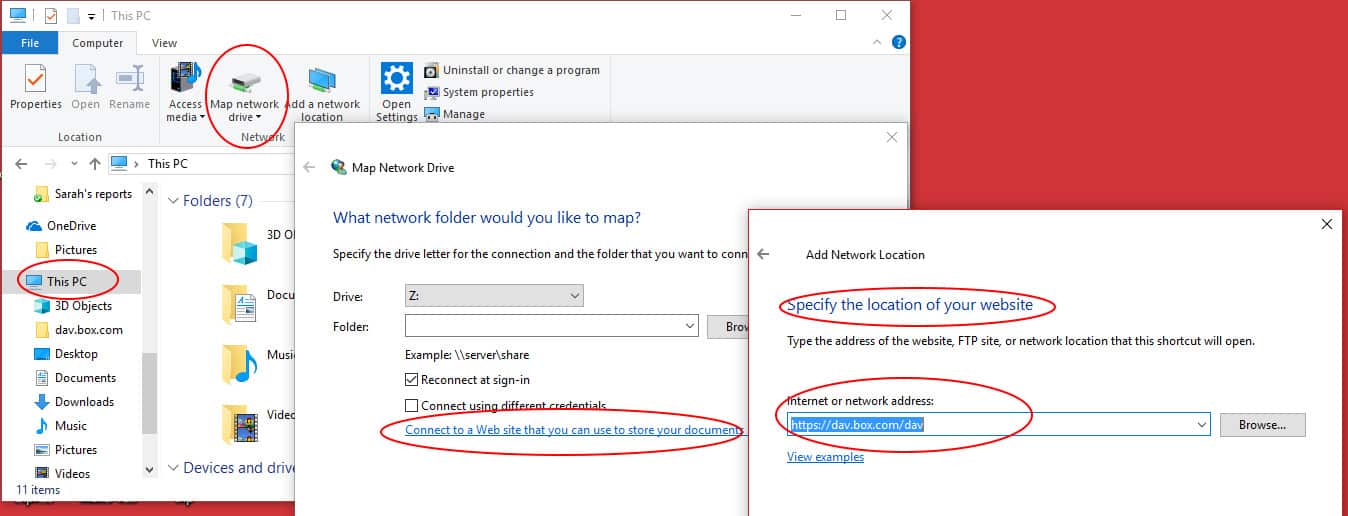

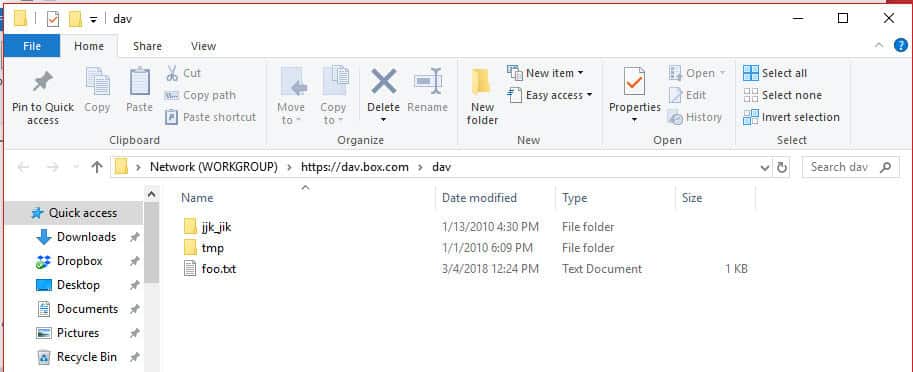

Most operating systems file managers’ user interfaces include an extension to present and manipulate WebDAV folders and files as if they were local. These include Windows file Explorer, macOS Finder, and GNOME Files (Nautilus) and KDE Konqueror on Linux.

In each case, there will be a “connect to server” option where you provide the WebDAV server’s URL (the URL format varies from tool to tool, sadly). You then provide the username and password for accessing the server.

The file manager presents remote files and folders, accessed via WebDAV, as local resources that you can click on, drag and drop, etc.

Filesystem modules

Multiple operating systems include the option of using a low-level filesystem module that mounts or maps a connection to a WebDAV server as a drive or mount. These include the Microsoft WebDAV Redirector, macOS WebDAV file system, and Linux GNOME GVfs and KDE KIO.

Once the operating system has mapped/mounted the WebDAV server, the files and folders exposed via WebDAV appear to be local. They are accessed by the normal file access calls, and any local application accesses them unaware of their true location.

Alternatives to WebDAV

WebDAV enables remote file editing and manipulation. There are many other mechanisms for working with files on a remote server; how is WebDAV different?

FTP

FTP (File Transfer Protocol) dates from the internet’s early days. The internet was a small town back then, so vanilla FTP’s security is completely inadequate for the mean streets of today’s internet. In contrast, WebDAV takes advantage of HTTPS security. FTP’s design is not firewall-friendly, where WebDAV relies on the standard mechanisms to support webservers. FTP requires its own server process, where WebDAV lives in the webserver. And FTP doesn’t include collaboration-oriented features like locking and version tracking.

There are descendants of FTP that address the need for security, by running an extension of FTP, or a workalike protocol, atop SSL/TLS or SSH.

SSH

The SSH (Secure Shell) protocol uses cryptography to securely provide operating system services like file access and command execution over an insecure network. Among the services are SCP (Secure Copy Protocol) and SFTP (Secure File Transfer Protocol).

SSH (and thus SCP and SFTP) requires its own server process and firewall rules, but support for SSH is almost universal on Linux and macOS and has recently become a built-in service on Windows 10 (previously third-party software was required). SCP only handles moving files, where SFTP can manipulate folders, delete files, etc. However, they lack collaboration-oriented features; the SFTP protocol does support file-locking but you can’t yet count on it being present and enabled.

Wikis

When we are talking about collaboratively producing content on the web, wikis are an obvious example. Wikis are group-edited websites that serve as project knowledge bases, note-taking tools, community websites, etc.

A wiki lets its users modify the content on pages, create pages, and modify the connections between pages, using a vanilla web-browser – no special protocols like WebDAV needed.

Wikis usually use a simplified markup language that’s much more limited – and quicker to grasp – than HTML. A wiki engine lives in a webserver like WebDAV. To permit a vanilla web-browser to edit, wikis don’t include the ability to edit multimedia files, and the only “file/folder management” that’s included is the ability to create and modify hyperlinks between wiki pages.

The wiki ideal is that the website is crowd-sourced and self-organizing; any user can make modifications and there is no predefined owner or gatekeeper. The anarchic ideal is often compromised; there are various wiki engines, and many support user authentication and imposing access controls on operations.

Distributed filesystems

There are multiple protocols for sharing remote filesystems across networks, whose most common use is to map/mount a network share exported by a server, permitting you to access folders and files on the remote server as if they were a local drive. SMB/CIFS is native to Windows; NFS is native to Unix/Linux; and for macOS the old default AFP is deprecated in favor of SMB.

These protocols provide essentially all the services of a filesystem on a local drive, including file locking, but not built-in file version tracking.

Distributed filesystem facilities often come with the operating system; if added later, they usually require additional modules added to the OS.

These protocols were developed to work over a LAN. Performance over the wide-area internet or a VPN will not be stellar, though you can mitigate that somewhat with tuning, and later versions of the protocols try to address this new use.

These protocols have much larger attack surfaces than simpler protocols like WebDAV. Though some recent versions like NFSv4 and SMB3 make improvements to support secure use on untrusted networks, most versions of these services are not secure beyond the LAN, and configuring them for such use is perilous.

Cloud file storage

Cloud storage services like Dropbox, Microsoft OneDrive, Google Drive, and Box.com seem like natural places for WebDAV. It does show up in some of them – Box.com is accessible via WebDAV, and OneDrive can be accessed by the standard Windows WebDAV facilities (though you only need this if you don’t have OneDrive file synchronization installed). Other cloud storage services provide their own specialized APIs, file-synchronization software, and web-app clients, and if you want WebDAV access you need to use a third-party gateway.

The specialized APIs, file-synchronization software, and web-app clients provided by the cloud services are designed to provide security and performance over networks like the Internet.

Related: The best ways to transfer and share large files

Why choose WebDAV?

Although there are alternatives to WebDAV and some of those are newer systems, none of the rival systems integrate all of the facilities of WebDAV. WebDAV’s key attributes are:

- Operating system integration

- Free to use

- Close integration with web services

- Version Control

- Transport encryption

- Remote access

- Centralized storage

- Version Control

- File locking

None of the alternative systems for file management have all of those attributes. You can transfer files securely with SFTP and SCP, but those protocols don’t include version control. WebDAV grants remote access control to documents in a central store rather than requiring files to be copied over to the user’s local computer and then copied back again.

You can buy software packages that manage collaborative authoring, but then you will be paying for a system that just duplicates the services of WebDAV, which you can get for free.

Although WebDAV is sometimes depicted as an outmoded methodology, it has served popular cloud storage companies very well to provide seamless local access to remote files. Modern working practices of job sharing, project management, collaborative authoring, development coordination, telecommuting, and cloud services create a requirement for services that WebDAV has been able to provide for decades. In a way, WebDAV was ahead of its time, and only now are businesses beginning to operate in ways that require the full set of WebDAV’s capabilities.

WebDAV servers and clients still going strong

WebDAV is a long-standing protocol that enables a webserver to act as a fileserver and support collaborative authoring of content on the web. In many of its use cases, WebDAV is being supplanted by more modern mechanisms. But it’s still a reliable workhorse when the right servers and clients are matched, so it’s still encountered in many different applications.

WebDAV FAQs

How do I find my WebDAV server address?

WebDAV doesn’t have a server address. When you set up a WebDAV connection, you are linking to a directory on your website. So, when you are asked for a server address, you need to enter the URL of your site. You will have the option of connecting to a specific folder on your web host. This is a better strategy than just communicating with the root directory. Set up a folder on your host files system with a name like WebDAVFiles before attempting to connect from a client device.

Different WebDAV implementations have different requirements. Some WebDAV interfaces have a separate field for the directory name. This is the case with the implementation on Ubuntu Linux.

Connect to a WebDAV server from Windows

When setting up a WebDAV connection through the Add Network Connection option in Windows, you need to give the full URL of your WebDAV folder on your website’s host. This should start with the schema, so you should have a server address that looks something like https://www.asite.com/WebDAVFiles

Connect to a WebDAV server from Linux

In the Linux WebDAV implementation, the server address should be given as the website URL without a schema or subdomain on it. That is, asite.com not https://www.asite.com The directory name should be entered in a separate field.

Connect to a WebDAV server from Mac OS

On a Mac, use the Finder tool to access the Connect to Server utility. Like the Windows network connection system, the Mac service requires the server name to have a schema and a subdomain and you should also put the path to your site’s WebDAV directory.

How to secure WebDAV with SSL?

WebDAV operates over the Web through HTTP and the easiest way to secure WebDAV transactions with SSL is to switch your site to the HTTPS schema. HTTPS is HTTP with SSL security features added to it. If your site has an active SSL certificate, the webserver will be able to negotiate connections with HTTPS instead of HTTP. In order to apply that security to your WebDAV traffic, use the HTTPS schema on the server address when you set up the network connection for it. That is, give the server name as https://www.asite.com instead of http://www.asite.com

Is WebDAV safe?

By itself, WebDAV is not safe. It is a plain-text system. However, the service can easily be implemented with HTTPS as the transport system, which is fully encrypted and, therefore, safe.

Is WebDAV faster than FTP?

There is mixed opinion over whether WebDAV or FTP is faster. In theory, WebDAV doesn’t need to establish a fresh connection to transfer each file and so the session establishment overhead is reduced, making WebDAV a little faster. However, there are many experts that claim to have tested both and found FTP to be faster.

industry-industry-4-network-points by Geralt, licensed under CC0.

WorldWideWeb (the original NeXT-based web-browser), c. 1993, Tim Berners-Lee for CERN – via Wikipedia.

I am using webdav over https mounted drive to Z:/ my question is related to DLP. When I drag and drop sensitive files from my local machine to the mounted webdav location is not being captured by my DLP software. The question is simple, how it works the network traffic? The time that it is an https connection it should be captured by my DLP but it doesnt so I worry about any security gap that might be. When I drag and drop is it a local action or through internet to the hosted server?

Thanks for the explanation. Complete and well written. Has helped me choose WebDAV over FTP.

Thank You. The explanation is easy to understand.

Super Tolle Mega Bombastische Erklärung! 🙂

Great post . thanks for sharing a clear step by step process on getting in the nice.

thank you.

Wow! Excellent explanation about WebDAV. Finally I get it now. I started at the Wikipedia article, then went to official DAV website, but ended up here because those write ups just left me confused. Now I know what WebDAV actually is and how it’s used. Thanks.

A very interesting and exhaustive article.

Thank you.

Stefano

Very good article. The issue with WebDAV is very poor built in client support on Mac’s and PC’s. This has given WebDAV a bad rap. There are some alternatives such as MyWorkDrive.com that provide the same types of access with added security of two factor authentication (not an option with WebDAV), file type blocking and data leak prevention.

Thank you for the clear and concise synopsis of WebDAV.

…

AND for the properly coded email address input box on this form!!! 🙂

John

Thanks. Very clear explanation