Privacy concerns are at the top of the list for internet users worldwide. The growth in online commerce and data exchanges crossing international borders, particularly between the U.S. and Europe, has also raised a number of government-level privacy concerns. Not all of this is due to criminal hacking. Much has to do with how businesses large and small are using customer data.

In an effort to better serve European users whose data crosses the US border, the United States Department of Commerce and the European Commission worked together to develop what is known as Privacy Shield, a regulatory implementation designed to guarantee European citizens are adequately protected under EU data protection laws as their data passes into and out of the United States.

An introduction to Privacy Shield

On July 12, 2016, the US government and the European Commission jointly approved the Privacy Shield Framework. The actual documentation for the Privacy Shield Framework provides a lot of valuable consumer information. However, it can be difficult to parse through the documents and glean exactly what it all means. Here’s a simple way to understand the concept.

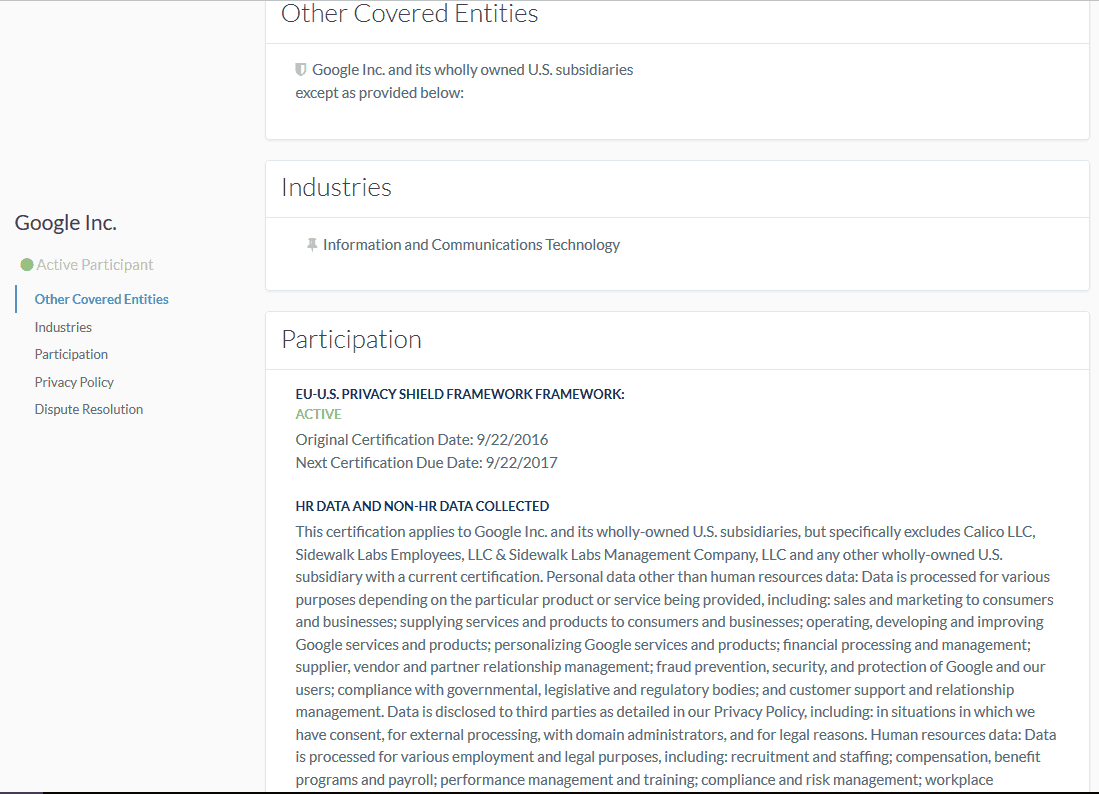

The United States and the European Union member states do a lot of commerce. In fact, transatlantic commerce produces nearly $5 trillion a year. Much of this commerce requires companies to collect data across international borders. In some cases, companies that bring in a multitude of customers and users from the European Union, such as Google or Facebook, collect and process tremendous amounts of user data.

At times, Google and Facebook may process that data, hold on to it for undetermined amounts of time, use it for metrics and analytics, or even pass it on to third parties for other purposes. Similarly, the US government may monitor some of that data or even collect it from those companies.

The European Union has a very specific law, the Data Protection Directive, that severely limits how businesses like Google or Facebook, or organizations like the NSA, can use or even collect data. This includes how governments can collect data from businesses for surveillance purposes. (The DPD is set to expire in 2018, to be replaced by new regulations that we discuss at the end.)

The Privacy Shield Framework operates as a set of rules governing US businesses with European operations. It allows businesses to do two things:

- Self-certify that they are agreeing to the Privacy Shield Framework

- Promote themselves and their adherence to the Privacy Shield Principles

Regarding Privacy Shield, the following are important to note:

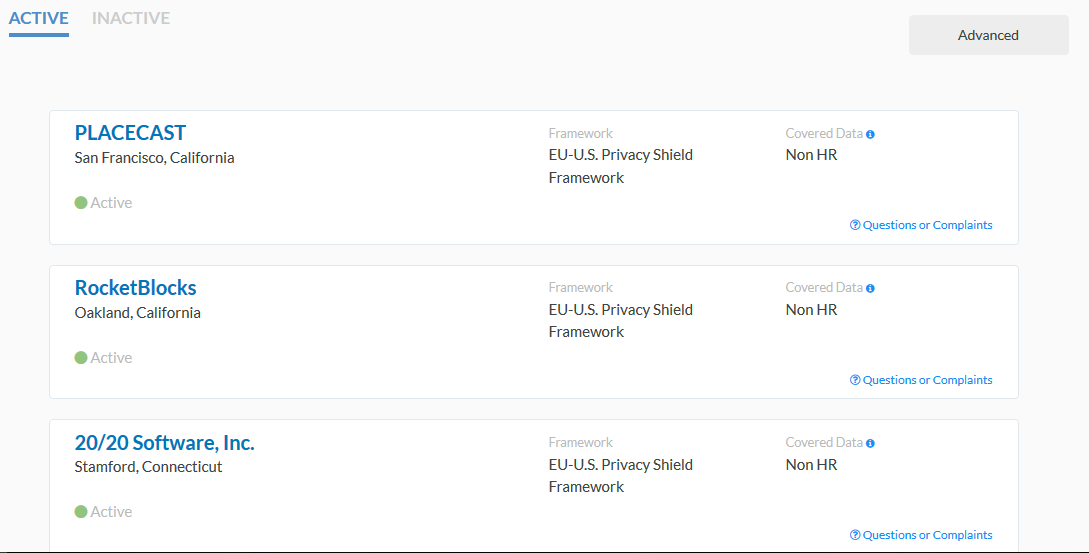

- Adherence to the framework is voluntary. However, there are currently hundreds of US businesses that have voluntarily self-certified. This creates an easy pathway for these businesses to collect private data from EU citizens for business purposes, increasing the flow of internet commerce.

- All businesses that agree to participate in the program must publicly post their participation. Once this is completed, businesses are strongly held to that standard, with a failure to follow the Framework resulting in potential fines of $21,842,000 or 4 percent of the company’s worldwide gross income for the year, whichever number is greater. Enforcement comes directly from the Federal Trade Commission’s rules prohibiting “unfair and deceptive acts”.

- Data breach reporting must be made within 72 hours. As Privacy Shield includes information security in its Principles framework, this is something businesses must take seriously.

Positively, many businesses already had the proper protocols in place to easily self-report.

What is Privacy Shield? A detailed overview

First, it’s best to understand what Privacy Shield is not, to help better frame the discussion of what it actually is.

Privacy Shield is not a data security program or software of some kind

This is important to understand, as the name might seem to relay a different message. Privacy Shield is not something users can install on their computers to protect their privacy, nor is it some kind of internet filter that monitors and filters or encrypts user data.

Privacy Shield is not mandatory for all U.S. businesses

Perhaps one of the larger weaknesses to the Privacy Shield Framework is the fact that it’s a completely voluntary program. In fact, it’s not even mandatory for American companies conducting business in Europe. Businesses that wish to participate must complete the self-certification process, which verifies that their business’s data privacy model aligns to the core principles of the framework.

Privacy Shield is not a two-way street

For all intents and purposes, Privacy Shield exists as a sort of rebuke to the US and its lack of organized regulation on behalf of consumer’s personal data. Privacy Shield was specifically designed for US businesses as part of a good-faith effort on the part of the US businesses to securely handle the data obtained from EU internet users in a manner more befitting European Union data protection laws.

Are the differences between US and EU data protection standards that significant?

Here’s the short version: The European Union has very strict standards in place to protect how someone’s personal data is both collected and used by companies and by governments. It boils down to the idea that individuals have a right to privacy first above a government’s or business’s right or desire to collect personal data for various purposes, even purposes that may be deemed worthy. Furthermore, it stipulates that anyone who feels their data has been misused has a right to file for redress from the company or the government that misused it.

If you have a few free hours (and perhaps a skill at parsing legalese) you can browse the specific language located in the Data Protection Initiative.

Meanwhile, the US has no formal legislation at the federal level protecting individual consumer data rights. This is why Edward Snowden’s sordid revelation of the NSA’s spying program caused so many waves. Many Americans and others around the world may have suspected that the US federal government was spying on individual, innocent citizens, but there was, up to that point, little in the way of verified proof. In 2013, Snowden provided that verification. The US spying program was so extensive and so broad that Snowden felt compelled to leak information on it only months after getting hired by the NSA.

The US Patriot Act gave rise to programs like PRISM and the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA) that collect data from US citizens and abroad. Many of the intrusions in the Patriot Act were severely limited by the 2015 Freedom Act, a law that extended the Patriot Act with significant limitations to how the government could collect data. These laws govern many of the protections Americans did not already have while imposing limitations on freedoms in ways unpopular in Europe. (We’ve explored the extent of the Patriot Act, the Freedom Act, and FISA, which you can read about here.)

That said, the US is not a Wild West of stolen personal user data, either from the government or otherwise. There are laws on the books across governmental departments at both the state and federal level. The biggest concern for the EU is related to the overall lack of a comprehensive and clear message within the US on how user data can be obtained and processed, as well as no clear indication on what rights individuals have for redress. The laws that do partially govern personal data protections in the US include:

- Federal Trade Commission Act

- Financial Services Modernization Act

- Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA)

- Security Breach Notification Rule

- Fair Credit Reporting Act

- Controlling the Assault of Non-Solicited Pornography and Marketing Act (CAN-SPAM)

- Telephone Consumer Protection Act

- Electronic Communications Privacy Act

- Computer Fraud and Abuse Act

- Judicial Redress Act (A US law that only provides citizens of EU member states the right to seek redress from governmental or law enforcement sharing of their personal data)

While the EU’s Data Protection Directive is far from light reading, the extremely varied mix of legislation in the US covering this topic makes for a bit of a bureaucratic nightmare while limiting an individual’s ability to better understand his or her rights regarding how governments and businesses collect and use personal data. Furthermore, many of these laws, while applied, are severely outdated and lack the language to best suit the current generation of computing and data processing.

How does the Privacy Shield Framework fix privacy issues?

According to the European Commission, personal data transfers outside the EU or EEA are not allowed when an adequate level of protection cannot be guaranteed. This means that businesses collecting data from EU citizens and transferring that data across borders, or EU citizens sending their data to US companies, were running into a legal impasse. The solution for this was the Privacy Shield Framework.

For European Union member nations and their citizens, Privacy Shield is intended to do several things:

- Provide transparency from companies in the form of public declarations as to their data usage policies

- Give individuals the opportunity to opt-out of having their data transferred to a third party

- Put in place safeguards to ensure that organizations transferring data to third parties are only transferring it to those parties for a limited use and that those third party recipients are also adhering to the data protection requirements

- Assurances that companies and organizations are protecting data from loss through security and encryption methods

- Protection from the misuse of personal data beyond the intended purpose

- Provide individuals with access to the information that organizations hold on them, with the option to amend, correct or delete that data where it either has inaccuracies or has been misused according to the Privacy Shield Principles

- Enforcement of the data protection principles via expedient arbitration for individuals who files claims, at no cost to the individual filing a claim, with proper investigation into the claim and verification or privacy protections, as well as fast processes of resolutions

This all may feel a bit hefty for the average internet user. Simply put, Privacy Shield exists as a set of procedures that US organizations and businesses must follow when processing individual user data, ensuring that its collection and use is compliant with European Union laws.

What does Privacy Shield mean for consumers?

For consumers, Privacy Shield serves one, main purpose: protection against the misuse and unwarranted collection of personally-identifying information. As Privacy Shield is designed to protect European Union citizens from the misuse of their data while it passes into and out of the United States, Privacy Shield only protects EU members and the three European Economic Area countries: Norway, Liechtenstein, and Iceland.

It is not designed to protect American consumers or extend to American consumers the same protections awarded EU members under the Data Protection Directive. Instead, Privacy Shield is an agreement between the US and EU that focuses on e-commerce and government surveillance. These protections also include bulk data collection, both from businesses and from the US government, where the wording includes significant limitations for what both businesses and US government intelligence and law enforcement agencies can and cannot do with personal data.

Most importantly for EU citizens, the incorporation of a redress mechanism and an Ombudsman task with handling privacy concerns were integral in ensuring that the tenuous agreement was able to pass muster.

What does Privacy Shield mean for businesses?

For businesses, Privacy Shield provides an element of trust to EU consumers and an easier pathway to use EU customer data. Prior to Privacy Shield, the system in place was known as Safe Harbor. These principles were similar to what currently exists in Privacy Shield, only with fewer, less restrictive privacy protections. After Austrian lawyer Max Schrems proved that the US-EU Safe Harbor Principles failed to cover his private Facebook data, the Court of Justice of the European Union invalidated the law in 2015. Safe Harbor had existed for 15 years, from 2000 until its invalidation in 2015. That it was drafted before major, data-collecting social media services like Facebook and the Patriot Act is indicative of why it failed to meet changing privacy demands and particularly those spelled out in the Data Protection Directive.

When Safe Harbor was invalidated, many US businesses could not legally collect or store data from European customers. As such, the EU and US worked quickly to draft a replacement, ultimately resulting in Privacy Shield. For businesses, this allowed operations to resume as usual, while also giving EU customers the added protections they desired with the use of their data. The updates to Privacy Shield from Safe Harbor forced a few changes for businesses:

- A required, detailed public statement regarding participation in the program. This statement must include a specific explanation regarding steps that the company is taking to ensure privacy is protected and that the company meets the Privacy Shield Principles.

- A tightening on data transfers and data sharing. Under Safe Harbor, third parties had few limitations on how they could use first-party data transferred to them. Under Privacy Shield, third parties are as limited in their use of data as are the first parties they obtain it from, and must also indicate their compliance to Privacy Shield.

- The FTC now maintains a “wall of shame” for those companies that violate the Privacy Shield Principles after publicly subscribing to them.

- Businesses must respond to redress concerns and must allow users to update, change or erase data upon request, so long as those requests are within reason.

Businesses involved in the Privacy Shield program must make sure that their data is secure, that they have are fully compliant with the Principles, and that their legal team and staff are fully aware of the FTC’s requirements related to Privacy Shield participation.

Large corporations are uniquely impacted

For large businesses like Apple, Facebook and Google, the Data Integrity and Purpose Limitation principle is indeed the most limiting aspect to Privacy Shield. This principle significantly limits how businesses can use bulk data for data analytics purposes, stating that “personal information must be limited to the information that is relevant for the purposes of processing”. Large social media sites have deep, legal concerns over the law. The man directly responsible for Safe Harbor’s ultimate demise, Max Schrems, believes that Privacy Shield is not sufficient for companies like Facebook, Apple, and Google, and expects it to ultimately fail.

Likewise, large companies are far more likely to store data and more likely to send customer data to third parties. This creates a tenuous position for these companies, as the limitations on storing data and on transferring that data to third parties is extremely limited. The chances of coming up against the Principles in a negative way are only increased for these large corporations.

Participation in Privacy Shield is voluntary

No business in the US is compelled to participate in Privacy Shield. Even businesses that want to bring in customers from Europe are not required to participate. That said, participation is strongly encouraged for businesses for one, primary reason: legal consequences.

Those businesses who choose to self-certify under Privacy Shield are identifying that they have aligned their data protection standards to those that meet EU legal standards for data acquisition and processing. This clarity goes a long way toward providing legal protections for that company. However, companies that choose not to adopt these standards make their lives more difficult. While it is possible to still do business in the EU, the lack of clarity leaves businesses more open to legal challenges. For the most party, Privacy Shield participation is a simple way to help decrease any legal challenges that may arise.

Privacy Shield does not protect businesses from government data requests

It’s important for both businesses and consumers to understand that Privacy Shield does not prevent the US government or law enforcement agencies from requesting data from businesses like Facebook or Google. However, Privacy Shield, alongside a revised version of the Patriot Act, significantly limited what kind of information can be obtained, and under what premise.

Nevertheless, many observers point out that the Privacy Shield Principles have clear weaknesses on this end, particularly when it comes to enforcement from US regulators. It remains to be seen whether an American company could be penalized under Privacy Shield for complying with a Federal government or law enforcement data request. However, Privacy Shield does provide businesses with an avenue and justification for denial, at least as far as EU citizens’ data is concerned.

Privacy Shield may have to change in 2018 with new EU regulations

Privacy Shield was designed to satisfy the privacy concerns of EU member states and its citizens by working with the Data Protection Directive. However, in April 2016, the European Commission passed a new law regulating data privacy concerns: The General Data Protection Regulation. The GDPR was designed to replace the DPD in 2018. This is because the DPD, which was passed in 1995, fails to adequately address the changes in technology that businesses and consumers are now dealing with, particularly those related to big data and its importance to business.

There are several noteworthy differences between the Directive and the Regulation:

- The new GDPR leaves little room for interpretation by individual member states, whereas the Directive was variably interpreted by different EU nations. This includes a new, single definition of what “personal data” actually means, something that the DPD also left up for interpretation.

- The new GDPR takes a hard line on how personal data can be used by organizations, requiring them to prominently display and explain how they intend to use data, and actually inform users when they want to use that data in different ways. There’s also a new “opt-in” clause to data storage, so organizations cannot simply store data by default.

- The new GDPR applies to all businesses and organizations that handle EU citizen data, regardless of whether they are participating in Privacy Shield or not. This widens the scope of the regulation to cover EU citizens’ private data beyond EU borders.

- Organizations must now also track how they use data and where that data goes. This information must be readily available upon request. Large organizations (250 employees or more) must have a Data Protection Officer to help track where data is moving within and out of the organization.

- Both data controllers and data processors are now responsible and liable for how data is used and protected. This means third-party organizations are as equally responsible as second parties.

- The GDPR includes a required breach notification policy. Any data breaches must be reported within 72 hours. This also results in an external investigation of the data security methods utilized at the time of the breach.

All of these rules should sound familiar. They coincide with much of what we find in the Privacy Shield Principles. This is not by accident. Privacy Shield and the new GDPR were worked out concurrently and designed to work together. However, the GDPR does not take effect until 2018. Many observers are waiting to see whether Privacy Shield will hold up well enough to make it an effective partner to the new GDPR regulations.

The largest concern currently resides with the “self-certification” process, which some observers view as Privacy Shield’s biggest weakness. With under two years to go before the GDPR takes effect, it remains to be seen whether Privacy Shield will hold up to further scrutiny.