Warrant canaries act similarly to canaries in a coal mine. Just as a canary’s death in a mine shaft signals that it’s filled with noxious gases, warrant canaries give companies a way to signal if they have received secret orders from the government to hand over user data.

Why can’t they just tell people?

Changes to US law made it illegal for companies to disclose when they received these orders. But the changes didn’t necessarily ban companies from publishing that they hadn’t received them.

This legal loophole gave birth to warrant canaries. If a company that hadn’t previously been issued a request regularly published a notice along the lines of “We have not received any secret requests from the FBI or other government agencies”, it could stop publishing the notice if it did receive such a request.

This gives the company a way to announce to the world that they have received an order, without actively declaring it and subjecting itself to legal penalties.

While the principle behind warrant canaries seems reasonable, their effectiveness is debatable, especially considering the abundance of these requests and the changing dynamics of data collection.

The history of warrant canaries

The concept of warrant canaries originated in response to the US’ passing of the Patriot Act in 2001. This broad-sweeping set of legislation introduced a range of reforms to combat terrorism. Among them, it expanded law enforcement’s surveillance powers, enhanced inter-agency communication and increased the penalties for terrorism-related activities.

The Patriot Act caused significant controversy among civil liberties advocates, with the Electronic Privacy Information Center calling the laws unconstitutional, and stating that “the private communications of law-abiding American citizens might be intercepted incidentally”.

One of the main concerns that relates to warrant canaries involved Title V of the Patriot Act, which altered the way that National Security Letters could be used. These are administrative subpoenas that the US Government issues for national security purposes. However they aren’t subject to approval by a judge, and the recipient is not allowed to disclose the fact that they have received such an order.

National Security Letters

National Security Letters (NSLs) were first created under the Financial Institutions Regulatory and Interest Rate Control Act of 1978, and allowed the FBI to obtain financial records only if:

- It could demonstrate that the suspect in question was a foreign power, or an agent for a foreign power.

- The financial institution consented to the letter—compliance with NSLs was voluntary.

Although an institution didn’t have to comply with an NSL, it was not allowed to disclose that it had received one.

Under the Electronic Communications Privacy Act of 1986, a new type of mandatory NSL was introduced, allowing government agencies to access “stored electronic communications information” (essentially stored data) from “wire or electronic communication service providers” (communications providers) only if:

- The information provided was limited to “subscriber information and toll billing records information”, as well as electronic communication transactional information.

- The information was “relevant to an authorized foreign counterintelligence investigation,” and there were specific and “articulable facts” that led them to believe the information relates to a foreign power.

- The NSL was approved by the Director of the FBI, or someone delegated to the task by the Director.

In 1993, Congress further relaxed protections against NSLs, opening them up not just to agents of foreign powers, but anyone allegedly communicating with foreign agents about terrorism or intelligence information.

In 2001, Section 505 of the Patriot Act stripped back the limitations on NSLs even further. The FBI no longer needed “articulable facts”, meaning that it could issue NSLs in even more questionable circumstances, as long as the information it sought was “relevant to an authorized investigation to protect against international terrorism or clandestine intelligence activities.”

It also allowed any special agent in charge of a bureau field office to certify NSLs. There are currently 56 field offices, which means that the power was expanded from one (or two, if the FBI Director had delegated someone) to more than 50 individuals.

Essentially, the Patriot Act’s changes made it far easier to issue NSLs and gave many more people the power to do so. All without a judge overseeing the process, and without the recipients being able to disclose that they had received one. If they did, they would face criminal penalties.

These legislative changes didn’t even outline a process for how recipients of an NSL could appeal. Nor did they specify whether they could disclose them to their legal counsel. It was only after a lawsuit that found NSLs to violate the First and Fourth Amendments that these provisions were added.

As you can see, NSLs slowly transformed over the years from subpoenas that could circumvent judicial oversight in extremely limited circumstances, into subpoenas that could get around checks and balances in a far wider set of situations.

Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court gag orders

NSLs weren’t the only relevant power affected by the Patriot Act. The 1977 Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA) was also altered. It was initially established to provide both judicial and congressional oversight to government surveillance of foreign individuals or entities in the US. It also set up the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court (FISC) to oversee requests for FISA warrants.

The Act allows the President to authorize electronic surveillance through the Attorney General without a court order for one year if:

- It is only to acquire foreign intelligence information

- It is only aimed at property or communications exclusively controlled by foreign powers.

- There is no substantial likelihood that it would acquire the contents of communications that involve a US Person.

- Certain minimization procedures are followed.

It also allows the government to seek permission for electronic surveillance under an order from the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court if:

- There is probable cause that the target of the surveillance is a foreign power or an agent of a foreign power

- There is probable cause that the places put under surveillance would be used by the foreign power or its agent.

- Certain minimization requirements are met.

These surveillance orders from the FISC can be approved or extended for 90 days, 120 days or a year at a time.

While surveillance requests to the FISC have to pass a higher barrier, and they at least undergo some sort of oversight, the proceedings are conducted in secret. The judges only hear evidence from the Department of Justice—there is no party that advocates for the denial of the request, like a defense attorney would in a normal court proceeding.

The only information reported is the number of warrants applied for, issued and denied. As of 2017, 40,668 out of 41,222 of these secret surveillance warrants have been approved. Only 85 were knocked back, while 1,252 were modified. With almost 99% approved without modification, it’s hard to accept that the judges of this secret court actually provide the proper scrutiny and oversight needed for such overwhelming invasions of privacy.

FISA requests were modified by the Patriot Act. Among the many additional provisions and powers, it allowed these court-ordered surveillance warrants to be issued for those that had no relationship with foreign entities. Even citizens could be subject to electronic surveillance if they were suspected of domestic terrorism.

One of the most relevant provisions for our topic was Section 215 of the Patriot Act. This allowed the Director of the FBI (or an official designated by them) to order third parties (those not suspected of whatever crime) to hand over materials that could assist in an investigation. This included papers, documents, records, books and other items.

These orders were gagged, so the person or organization that received them was not able to tell the public, or the affected individual. However, Section 215 expired in 2020, so these specific overreaches are no longer legal except in investigations that were ongoing at the point of expiration. While these provisions are expired at the time of writing, there is no guarantee that they won’t return in the future.

Electronic Communications Privacy Act gag orders

This third major set of legislation doesn’t get as much press, but according to a paper published in the Harvard Law Review, it could be involved in a large number of electronic surveillance warrants that are subject to gag orders.

The Electronic Communications Privacy Act of 1986 (ECPA) was established to set out protections for telecommunications, but it also stipulated certain exemptions. Our main concern is Title II, which enacted the Stored Communications Act.

Among other provisions, this Act set out laws to address both compelled and voluntary disclosures of electronic communication as well as transaction records from ISPs. However, it seems to currently be applied to most data-gathering tech companies.

The government can compel a provider to hand over an individual’s records if it obtains a warrant from a court, and the information has been in electronic storage for 180 days or less.

Alternatively, if the data has been stored on a remote computing service for more than 180 days, government entities can obtain the records if:

- They obtain a warrant issued under the procedures of the Federal Rules of Criminal Procedure (or the corresponding procedures for State or Military court).

Or

- The government entity gives prior notice to the subject of the records through an administrative subpoena or a court order.

There are a few other situations and details, but going into them isn’t particularly relevant. Most importantly, Section 2705(b) allows for the provision of gag orders when these records are disclosed.

Government entities can apply to the courts to withhold notification. Courts will grant the gag order if they determine that disclosure will have adverse results. Just like NSLs and FISA warrants, the provider may not be able to tell the public or the affected individual that their records have been accessed.

How these legislative changes led to warrant canaries

New or altered laws weren’t the only major change during the post 9/11 period. Technological advancements were also altering the type and amount of data that communications providers accessed and stored. It was no longer just a few phone records and basic customer information. The likes of Facebook, Google and Amazon wound up knowing almost every aspect of our lives.

Amid these shifts, certain people, civil liberties organizations and technology proponents began to worry about the privacy ramifications. Many saw the dangerous precedent set by the legislative changes of the Patriot Act. They correctly predicted that communications providers and other organizations could be forced to hand over data on individuals with limited judicial oversight.

The changes meant that the FBI was able to obtain the records of individuals on the flimsiest of reasoning. Other government entities had very loose judicial processes that they could turn to.

The companies that received these orders could even be gagged and couldn’t tell anyone that they had received an NSL, FISA order, or another type of gagged subpoena. They couldn’t tell the person whose records were involved, nor the general public.

Even if the recipient tried to appeal the order (once the appeals process was outlined in the 2005 legislation), they had to keep quiet while the case was resolved.

Steven Schear

In 2002, the year after the Patriot Act was passed, Steven Schear posted a comment on a Yahoo! Cypherpunk messageboard that outlined how ISPs could notify the public that they had received an NSL, without violating the legislation.

He reasoned that:

- If someone wasn’t the subject of an NSL, there was no law stopping an ISP from telling them that the authorities had not requested their records.

- If an ISP had received an NSL for that person, they cannot be legally forced to lie to them.

Therefore, the nondisclosure requirement could be circumvented by setting up a system where people could call their ISP and just ask whether it had received an NSL related to them.

If none had been received, the ISP could simply answer truthfully and say no. If it had received one, it could just refuse to answer. This would tell the person that they were the subject of an NSL, without the ISP ever having to actively break the law.

This was the birth of warrant canaries. Just as miners didn’t have to die in the shaft for anyone to find out that the air was poisonous, the companies didn’t have to explicitly tell the individuals subject to NSLs that a letter had been received.

The dead canary—the lack of a response—signaled all of the information they needed, and the subject could then act appropriately, whether that meant taking up legal counsel in anticipation or moving to another service.

Librarians vs the FBI

Librarians may not have the best reputation for being cool, but they were one of the more prominent groups to stand up to against government overreach at the time. They were particularly concerned about Section 215 of the Patriot Act, which amended FISA. This section compelled librarians to hand over reading records for those under investigation. They were not allowed to disclose when this had happened.

One of the more prominent librarians to push back was Jessamyn West. She worried that the changes could lead to a range of abuses, including things like people ending up on the no-fly list, purely for borrowing a book about Islam.

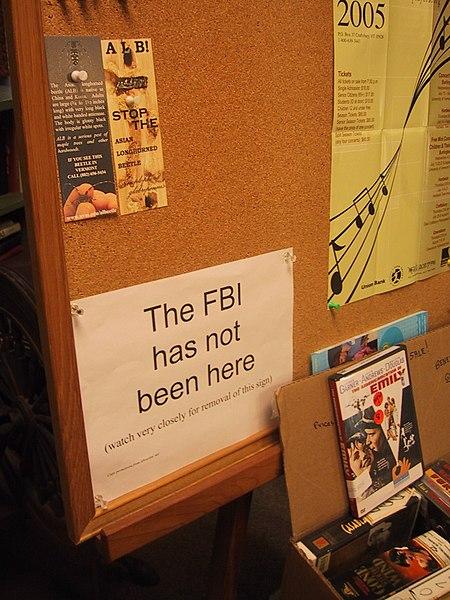

In response, she created a series of signs like this:

The FBI has not been here by Jessamyn West licensed under CC0.

The idea behind these signs was to notify visitors if the FBI had been to the library. If they had accessed records alongside a non-disclosure order, the librarians were forbidden from alerting anyone.

However, if they had previously put up a sign declaring that the FBI had not been there, there was nothing to stop them from taking it down if they did come. There was no law that compelled them to lie. Therefore, if a regular visitor noticed one day that the sign was gone, they would know that the FBI had been there, sniffing around the records.

These signs acted like warrant canaries, and they began popping up in libraries all over the country.

However, you will notice a difference between the librarian’s tactic and the system that Steven Schear thought up. Schear proposed a warrant canary system that would allow individuals to check if their own records had been accessed by the authorities, while the library signs could only tell the public that they came looking. Their signs could not notify the specific person who was targeted, only that the FBI had been there.

On top of this, they were only really useful before the FBI had come to investigate records. After it happened once, there was no additional sign to remove on any subsequent FBI visits.

Although this limited the utility of warrant canaries, this is the direction they headed in as they became more widely adopted.

rsync.net

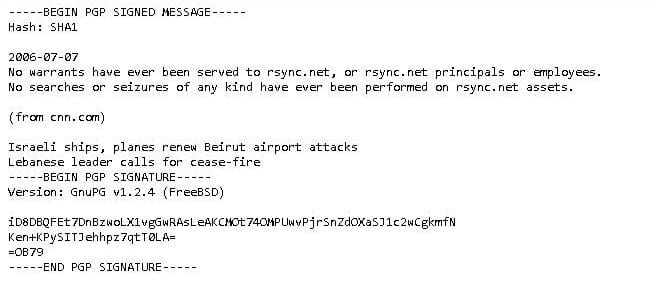

The first instance of a warrant canary in its more modern form was posted by the cloud storage provider rsync.net in 2006. The company acknowledged the legal provisions for secret warrants, as well as the criminal penalties that a provider could face for revealing one.

It said that it would comply with these warrants, however, it would also post weekly, cryptographically signed warrant canaries which would indicate that, at the time of posting, no warrants had been served, and that no searches had taken place.

rsync.net’s canary instructed users to take note if the message ever stopped being updated, because this would imply that the company had been secretly forced to hand over records.

rsync.net’s warrant canary.

Although the warrant canary wasn’t foolproof and could be compromised by coercion (if the government secretly forces any company to lie, it would make their warrant canary meaningless), it aimed to let the company’s users know if the government had ever accessed a single record.

One of the positive aspects about rsync.net’s warrant canary is that it’s updated each week. If the company’s records are ever accessed by the government, users would know quite soon afterwards. However, the warrant canary would not tell them who was the subject.

rsync.net has continued posting warrant canaries up until the time of writing, and it still states that no warrants have been issued, nor searches conducted at any of the company’s locations.

Proliferation of warrant canaries

rsync.net’s approach didn’t really gain much ground in the following years, but in 2013, a bombshell dropped. Whistleblower Edward Snowden unveiled a host of alarming mass-surveillance practices, including the NSA’s PRISM and MUSCULAR. The revelations put Government overreach and privacy invasions at the forefront of everyone’s mind.

Amid this turmoil, Apple became the first tech giant to adopt a warrant canary at the end of 2013. It was published in the company’s inaugural transparency report, which detailed the types of requests that the company had received, as well as rough information on how many.

Its warrant canary was very specific:

Apple has never received an order under Section 215 of the USA Patriot Act. We would expect to challenge such an order if served on us.

The warrant canary did not make any mention of Section 702 of the FISA act. If you read between the lines of this omission, it seems likely that the company had been subject to orders from the secret court.

Apple’s warrant canary was soon followed by Reddit, Tumblr and many others. While these were certainly positive steps, it was quite difficult for people to keep track of all of these warrant canaries.

The only way anyone could find out if the authorities had accessed records from an organization is if they went to the company website and saw that the warrant canary had stopped being updated, or caught a news story reporting on the cessation. There was no central hub.

Canary Watch

The problem of keeping track of canary warrants was addressed by Canary Watch. It was formed by a coalition of organizations that included the Electronic Frontier Foundation, New York University’s Technology Law and Policy Clinic, the Freedom of the Press Foundation and others.

Canary Watch listed known warrant canaries, allowed submissions for unlisted warrant canaries and kept track of existing canaries. It provided a central location that users could visit to see whether a certain organization had a warrant canary, and if it was still valid.

The site also served to raise awareness for warrant canaries and the associated privacy issues. The project wrapped up about a year after it started, by which time it had almost 70 warrant canaries in its database.

In May of 2016, the Electronic Frontier Foundation released a blog stating that the project had achieved its goal of popularizing the concept of warrant canaries and that the coalition behind it had come to an agreement “…that the project has run its course and has come to a natural ending point.”

Some warrant canaries begin to die

Just as the concept started to become more popular, some the warrant canaries began to disappear. Apple’s warrant canary was only with us for a very brief time. By September 2014, GigaOm noticed that the warrant canary was already gone.

In 2016, Reddit also neglected to update its warrant canary. It didn’t make any public announcements about the warrant canary being dropped, but a user noticed its absence in a thread about the latest transparency report. Reddit’s CEO u/spez added more mystery to the situation by elaborating that, “I’ve been advised not to say anything one way or the other.”

This achieved widespread attention both on Reddit and tech news sites, with the EFF’s blog on wrapping up Canary Watch mentioning the Reddit situation as a likely reason for the huge growth in warrant canary-related internet searches.

Silent Circle

Secure communications company Silent Circle also found itself embroiled a minor controversy. At the end of 2014 Hacker News began speculating about why its warrant canary was out of date. Many of the commenters assumed that the lapse was just the warrant canary working as intended, and that Silent Circle had received a gagged order to hand over user data.

Maybe it did. But there’s also a chance that it didn’t. What if the company just forgot?

Amid the suspicious and mostly negative commentary, a user purporting to represent rsync.net claimed that their company had missed its normal publishing date about 10 to 15 times over the nine years that it had been updating its canary. If this comment is to be believed, then it seems reasonable to assume that companies can just forget, especially during hectic times.

The warrant canary was later updated, but in March the following year, there was another debacle when it was pointed out that the latest version of the warrant canary lacked a clear statement saying that the company had not received any gagged orders up until that date.

The company soon fixed the issue, but about a year later, it completely removed its warrant canary. The company’s general counsel Matt Neiderman said that it hadn’t received any secret warrants, and had simply removed it for business reasons.

Silent Circle’s chief strategy officer Vic Hyder went on to explain:

“The main reason [we cut it] is it was of little benefit to our enterprise customers, with whom we have contracts… We cannot, literally, provide access to the encrypted data whether messages or voice. Neither do we log service usage, and the only other information we maintain is customer data primarily for billing purposes. The canary was an unnecessary maintenance requirement which we shut down nearly two years ago, I believe.”

This kicked up another storm with users and commenters. But what should we make of the whole situation?

It’s really hard to say. Perhaps the trail of events was the company’s way of dealing with a gagged warrant. Maybe there was no warrant, and the whole situation was just a number of fumbles that caused so much bad publicity that the leadership just thought, “Screw it. This warrant canary is more trouble than it’s worth.”

Either way, the company could certainly have handled the situation better. If it did receive a warrant anywhere along the line, it should have just immediately stopped updating it, and the silence would have been enough for users to get the picture.

Frankly, the way that the situation was handled and the company’s statements surrounding it made the warrant canary a liability. Security requires trust in the service providers, and Silent Circle’s mistakes cast doubt among their users, in the tech press, and online. Silent Circle’s situation is a good example that if a warrant canary isn’t being administered properly, it probably isn’t worth the possible fallout to the company.

But was Silent Circle’s warrant canary useful to its users?

Not really. The whole situation leaves them not knowing very much. Sure, the warrant canary was removed, but we can never be 100 percent certain of the reason. If the company hadn’t been served any gagged warrants, and the events were purely due to its own errors, it did have a legitimate business reason to drop the warrant canary—to stop the negative publicity.

On the other hand, perhaps the company was served a gagged warrant for user data, and it used the ‘business reasons’ excuse as a way to save its reputation and retain customers.

As outsiders, we’ll probably never know what really happened, so what should users or potential users of Silent Circle products do?

The prudent decision would be to assume the worst, just to be safe. But if we assume that a company has had its records accessed, what’s the logical next step?

What should you do if your service provider’s warrant canary expires?

So, your service provider has stopped updating its warrant canary, leading you to assume that at least one person’s records have been accessed by the government. You do not know whether your records are involved, although for any big company, it’s statistically unlikely that yours would be the first records.

You can’t know how many records were accessed, or if government agencies continue to access the records. Warrant canaries only work once, and they don’t leave you with a lot of information.

Your options are to either stay on the service, despite its lack of a warrant canary, or to move to a competitor. If you move to a competitor with an intact warrant canary, it still can’t offer you any additional protection.

Just because a company still has its warrant canary doesn’t stop law enforcement from ordering any records that they want in the future. At best, all a competitor can do is tell you if or when the government comes knocking for the first time. That’s the only real edge it has over a provider that no longer has its warrant canary. It cannot offer you any additional information

You could keep jumping to new service providers each time one lost its warrant canary, but it doesn’t really achieve much. It also punishes honest companies who drop their warrant canaries when served gag orders, because they will no longer get your future business.

Just because a company has received an order doesn’t mean it has done something wrong or that it doesn’t care about your privacy. If it’s served an order, there isn’t much it can do. A company may be able to appeal, but if the order was issued in secret, then the appeal has to be as well.

In many cases, companies will lose the appeal. At this stage, all a company can do is give in and tear down their warrant canary, or defy it and face criminal charges. It could also choose to completely shut down its service, but this could still lead to charges.

Just take a look at what Lavabit’s owner went through when he shut his business to defy an order. Because of what’s at stake, most companies will end up complying, no matter how much they wish they didn’t have to.

The other thing that you should consider is that it makes sense for the authorities to go to the companies with the largest user bases and the most data first. These companies are the most likely to have information that’s useful in an investigation.

Therefore, the most popular platforms were going to lose their warrant canaries first. While there are still a bunch of smaller companies that maintain their warrant canaries, it’s probably because they don’t have much data that the authorities want. It does not mean that they offer additional protections.

Those with intact warrant canaries aren’t necessarily privacy bastions. They just may not be on the radar of law enforcement.

Do warrant canaries really work?

For a warrant canary to work, it relies on the presumption that the government cannot compel a person or an entity to lie. However, the specifics of warrant canaries have never been openly put to the test in court.

We can’t be certain that the government hasn’t or wouldn’t secretly coerce companies to continue updating their warrant canaries despite an order having been issued. Due to the secrecy inherent in many of these orders, it isn’t out of the realm of possibility. In essence, we can’t know for sure whether or not the government has forced organizations to lie about their warrant canaries.

The usefulness of warrant canaries has been questioned by some of the most prominent security and privacy experts. Renowned cryptographer Bruce Schneier stated:

“…I have never believed this trick would work. It relies on the fact that a prohibition against speaking doesn’t prevent someone from not speaking. But courts generally aren’t impressed by this sort of thing, and I can easily imagine a secret warrant that includes a prohibition against triggering the warrant canary. And for all I know, there are right now secret legal proceedings on this very issue.”

Signal’s founder and CEO Moxie Marlinspike offered similar sentiments:

“If it’s illegal to advertise that you’ve received a court order of some kind, it’s illegal to intentionally and knowingly take any action that has the effect of advertising the receipt of that order. A judge can’t force you to do anything, but every lawyer I’ve spoken to has indicated that having a “canary” you remove or choose not to update would likely have the same legal consequences as simply posting something that explicitly says you’ve received something…”

Transparency reports

While the effectiveness of warrant canaries was being hotly debated, a related concept also began to gain ground. The first major transparency report was released by Google in September of 2010.

It featured an interactive map that allowed people to see which governments around the world were demanding that Google remove content, where Google services were blocked, and which governments had requested user information.

While the original interactive map is no longer available (Google restructured its transparency reporting tools), a Mashable article tells us that it included the total number of government requests by country and by which service (Gmail, YouTube, etc.).

The article states that there were 4,287 requests for user information from the United States Government in the first half of the year. This figure included all types of requests but excluded those with gag orders. Mashable pointed out that Google’s FAQ stated:

“We would like to be able to share more information, including how many times we disclosed data in response to these requests, but it’s not an easy matter…”

However, in this first edition of the transparency report, Google did not specify how many of these requests it complied with.

In Google’s blog post announcing the transparency report, it stated:

“We view this as a concrete step that, we hope, will encourage both companies and governments to be similarly transparent.”

In Google’s subsequent report, which tallied the number of requests between July and December of 2010, it included the percentage of requests that the company complied with. Of the 4,601 requests it received from US authorities, it complied with 94 percent.

Transparency reports begin to gain ground

Inspired by Google, Twitter launched its own transparency report in 2012. Twitter’s report included information about the number of:

- Government requests received for user information,

- Government requests received to withhold content, and

- DMCA takedown notices received from copyright holders.

It included data from all over the world, but we will stick to the US figures. Of the 679 requests that Twitter received from US authorities, it complied with 75 percent.

In the wake of Edward Snowden’s revelations, many more companies started following Google and Twitter’s lead. Sure, much of it was probably a PR push after people’s trust in tech companies took a significant blow, but we now have transparency reports from the likes of Facebook, Microsoft, Uber, Apple and many more.

Transparency reports are usually done under a company’s own initiative, so there are no regulations for how they should be structured. While some companies create maps and interactive tools like Google does, many others just publish them as simple written reports.

Each company will offer different services, collect data in different ways, and receive varying law enforcement requests. They also have their own motives for releasing the reports, so they may end up including different types of information. Some companies include warrant canaries in their transparency reports, but most of the bigger names do not.

Bringing more detail to transparency reports

Up until this point, companies were limited in what they could reveal in their transparency reports. If they were issued secret orders, they could not include them in the reports unless the gag had expired. They mostly listed the total number of requests received, without much information on the type of requests or their relative quantities.

In March of 2013—before Snowden—Google reached a deal with US authorities and became the first company that was granted permission to publish the number of National Security Letters that it received, but only in broad ranges.

In a blog posted by Legal Director Richard Salgado, the company stated that it published the numbers as ranges rather than exact figures to “… to address concerns raised by the FBI, Justice Department and other agencies that releasing exact numbers might reveal information about investigations.”

In Google’s transparency report, it revealed that it had received 0-999 National Security Letters each year. These letters were connected to:

- 1000-1999 accounts in 2009.

- 2000-2009 accounts in 2010.

- 1000-1999 accounts in 2011.

- 1000-1999 accounts in 2012.

Later in the year, in the wake of Snowden’s 2013 revelations, Google issued a letter to the offices of the FBI and the Attorney General, in what seemed like a bid to distance itself from the public perception that it was indiscriminately handing over data to the government.

The letter stressed that the nondisclosure obligations of FISA requests fueled negative speculation, and asked for permission to publish the aggregate numbers of national security requests, including FISA orders. Google asked to be able to include both the number of requests it receives and their scope in its transparency reports.

By September, Google, Microsoft, Facebook and Yahoo! had filed motions with the FISA Court, asking to be allowed to reveal more details about the number of FISA orders they were receiving.

At the start of 2014, this culminated in a deal between the Justice Department and these four companies, which allowed them to disclose the number of FISA orders they received in aggregate, but with a six-month delay and only in bands.

With this ruling, the companies revealed that for the January to June period of 2013:

- Google gave the government metadata for 0 to 999 accounts, and the content of communications from between 9,000 and 9,999 accounts.

- Microsoft received under 1,000 orders for metadata, as well as under 1,000 orders for communications content, which was related to between 15,000 and 15,999 accounts.

- Yahoo! gave the government metadata for less than 1,000 accounts and communications content from between 30,000 to 30,999 accounts.

- Facebook turned over customer metadata for 0 to 999 accounts, while it disclosed content data for 5,000 to 5,999 accounts.

In 2015, Section 603 of the USA Freedom Act codified much of this into law, offering four different reporting methods to those that are subjected to FISA nondisclosure requirements.

Companies were allowed to release the aggregate number of orders, directives or letters received on a semiannual or annual basis. However, they were still restricted to reporting these numbers in wide bands, rather than the precise number of requests received.

Back in 2014, Twitter filed a case asserting that it had a First Amendment right to share the total number of surveillance orders it had received over a six month period. It was also seeking to affirm its right to disclose whether it had not received certain orders—effectively fighting to affirm its right to publish warrant canaries.

This case followed Twitter’s 2014 draft submission of its transparency report to the FBI. The report contained the numbers of secret surveillance orders it had received, and was ultimately censored.

This censorship sparked the six year legal battle, which ultimately concluded in April 2020 when the judge accepted the Government’s claim that the state secrets contained in its declarations did not have to be turned over to Twitter’s counsel due to national security concerns. The judge then held that these concerns were sufficient to justify censoring Twitter’s draft 2014 transparency report.

In case it’s not clear, Twitter’s legal counsel never even got to see the declarations, despite having high-level security clearances. The judge sided with the government, even though Twitter never got to see why.

Are transparency reports more useful than warrant canaries?

In the cases of large companies that frequently get these requests, it’s been a while since warrant canaries have been able to provide much useful information. While some of them did have warrant canaries in the past, once they received secret requests, they couldn’t display them anymore, so warrant canaries were no longer a way that they could display information to their users.

The circumstances are different for smaller companies whose information doesn’t seem to be as highly prized by the authorities. If a warrant canary is still regularly updated and there haven’t been any strange occurrences, then they generally do a good job at notifying users that the company has not received a gag order.

While many of these smaller companies are doing great work by trying to keep their users as informed as possible, the reality is that most people probably have vast swathes of data tucked away on the servers of these major companies that no longer have warrant canaries.

In these situations, transparency reports are our only hope for any solid data. But even the information that these companies display in their transparency reports may not be particularly useful.

We can track each company’s reports year on year, to see if the number of requests it receives is growing. We can also look at the stats from different countries, and see which governments are the most demanding. We can look at which companies have the highest rates of complying with government orders as well.

But many of these figures don’t offer much practical information that we can act on. Sure, we can see if governments are getting hungrier and hungrier for data. But do these figures really tell us anything about the company and its attitudes toward protecting its users?

Certain companies may get a lot more requests than others because they have the kinds of data that are most helpful to investigations. Or, they may have higher proportions of criminal activity on their platforms. The overall number of requests doesn’t necessarily tell us much on its own.

Likewise, the percentage of cases in which a company complies with the authorities may be an indicator of how much they are willing to stick up for their users. But there could also be certain legal reasons why one company ends up having to hand over more than another. Without any context on a case-by-case basis, the information we get from these reports isn’t clear enough to help us make decisions.

Even if we could clearly tell which companies were least likely to protect their users, what would we do about it? Move over to a competitor? If this new company collected and stored data in a similar way, there’s only so much they could do to protect us if law enforcement was really banging down their doors for the data.

Let’s face it, most companies aren’t going to put themselves at risk to protect a user. The only time a company has closed down instead of complying was the Lavabit fiasco we mentioned earlier, and that was only because the government wanted access that could compromise the data of every Lavabit user.

The argument isn’t that this legal situation is acceptable—it’s not. There needs to be far more transparency in all of these investigations and legal processes. Certain powers should also be stripped back. In fact, the entire system and its regulation probably needs an overhaul.

But this is the situation we’re currently in, and there don’t seem to be any major changes that will protect us on the horizon. The reality is that neither transparency reports or warrant canaries do much to help us.

Are there better alternatives

We live in unprecedented times. No company has ever held as much information on us as these tech giants do, and it can all be handed over to the government, without us ever knowing about it.

In earlier eras, you would probably know if the government searched your house. Our online profiles may contain far more intimate information, and all of it is fair game, often without any judicial oversight.

But there has been one proposal for how we could be notified if our online records are accessed. However, it rests on dubious legal grounds, and has yet to be implemented.

Granular warrant canaries

As we have discussed, warrant canaries don’t really tell us too much. If a platform has thousands or millions of users, and its warrant canary goes missing, you don’t know if it’s just for one person’s records or many records. You certainly have no idea whether it involves your own information.

But if we remember back to the man who came up with the concept behind warrant canaries—Steven Schear—he originally described a per user system. Anyone would be able to call up their ISP, and ask whether their individual records had been accessed. If the employee said ‘No’, they were safe, but a lack of response would mean that the records had actually been accessed.

At least in this type of setup, a person could find out whether they were being investigated, which seems far more useful than just knowing that someone in the user base had their records accessed.

While having to call in to check with a company would be a hassle for both the user and the business, it at least seems possible for these platforms to include a “Your data has not been accessed by any law enforcement agencies” notice on people’s user profiles. If companies ever did receive a request from the authorities, they could simply strip away that notice. This would alert the user, without the company ever explicitly saying anything.

While something like this is technically feasible, it has yet to be implemented by any organization. Even broader warrant canaries stand on shaky legal grounds, so personalized ones could land companies in trouble.

The legal grounds for granular warrant canaries

A 2015 article published in the Harvard Journal of Law & Technology examined how the courts would view personalized warrant canaries. It stated that this type of granular warrant canary had the greatest potential to compromise national security investigations “…because they could alert their target of an investigation of the government’s search, prompting that individual to cease use of the targeted service, and to attempt to erase his or her information therefrom.”

It went on to say that the government has a strong interest in preventing this from happening, and concluded that courts would be less likely to find these canaries legal.

The article stated that warrant canaries are subject to a “means-ends” strict security analysis, and that “Courts are unlikely to apply First Amendment protection to the hypothetical canary that provides personalized daily notices to individual user accounts, given the actual damage it could inflict on a legitimate investigation.”

It contrasted personal warrant canaries with broader warrant canaries, concluding that warrant canaries that don’t inflict harm on the government’s national security interest are “almost certainly” protected by the First Amendment.

The idea of warrant canaries that are granular down to the individual level has been around from the very start, and it would be trivial for companies to implement such systems.

However, we still haven’t seen any organizations set one up. It seems that companies are too scared of the potential legal ramifications to do so. If there wasn’t such a legal gray cloud hovering over their heads, you would theorize that at least one company would attempt personalized canaries as a way to stick out from the crowd.

Use service providers that store your data in other legal jurisdictions

If personalized warrant canaries don’t seem to be on the table, then what about keeping your data out of their reach?

You would need to choose a provider based in a country that doesn’t collaborate with your own country in investigations, or one that has a much stricter legal process. If you are US-based, you would probably want to stay away from other Five Eyes countries, because their intelligence services tend to work closely together. It’s probably best to also stay away from authoritarian countries and those without due process as well.

Countries with some of the best privacy laws include Estonia and Iceland. If you use services that are both based in and store their data in these countries, you will be offered greater protections against nosy law enforcement.

Don’t give them data in the first place

If you are truly concerned about the government using these powers to secretly collect your data and use it against you, warrant canaries and transparency reports aren’t going to do much to help you.

You can use the services of companies that still have intact warrant canaries, but if the government really wants your data, you could be that special person whose data request ends up killing the canary. Warrant canaries simply can’t protect you if the authorities want your information badly enough.

The only way you can truly protect your data is to minimize how much of it ends up in the hands of companies. It would take another article just as long as this one to describe all of the intricacies, but some basic pointers include:

- Use Signal instead of Facebook Messenger

- Use DuckDuckGo instead of Google

- Use TOR for sensitive web activity

- Use a no-log VPN

- Lock down your browser

- Avoid social media

The above is just a start. Some more comprehensive sources of information are privacytools.io and PRISM BREAK. Escaping data collection and the government’s ability to access your information is a long, complicated and arduous process.

Most of us will never take it to the extremes, but even a few simple changes can dramatically cut down the information that is collected on you, and the amount of data that could end up in the hands of the authorities.