An independent review (PDF) of terror legislation by David Anderson says the UK’s spying agencies–the GHCQ, MI5, and MI6–should be allowed to continue using “bulk interception” to fight against terror. Anderson’s report, ordered by Prime Minister Theresa May, argues that there is no viable alternative to the mass collection of data from emails and other communication data.

“Where alternative methods exist,” the report reads, “they are often less effective, more dangerous, more resource-intensive, more intrusive or slower.”

Anderson makes a case for bulk interception of communications data, metadata, and databases of personal information. It would seem most Brits agree with him and Prime Minister May, who welcomed the report’s findings. Earlier this year, Comparitech.com commissioned a survey conducted by OnePoll of 1,000 people across the United Kingdom. The survey questioned respondents on government bulk surveillance and the sale of their personal data to third parties.

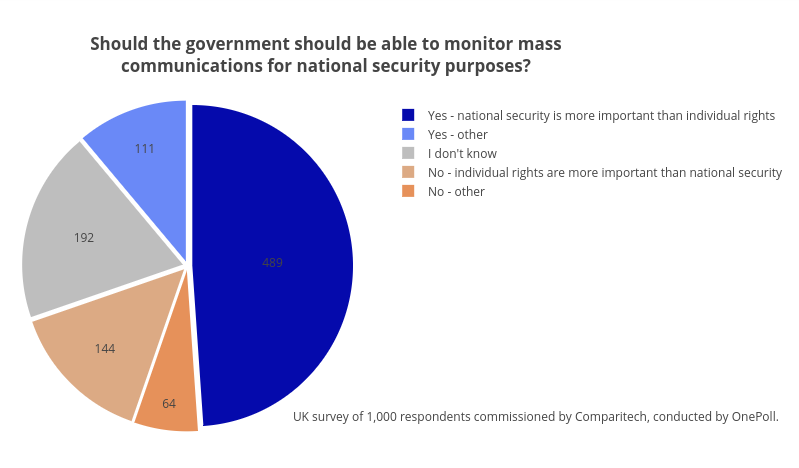

60 percent of the Brits surveyed said the government should be able to monitor mass communications. Nearly half agreed that national security is more important than individual rights. Only one in five gave a flat out “no”.

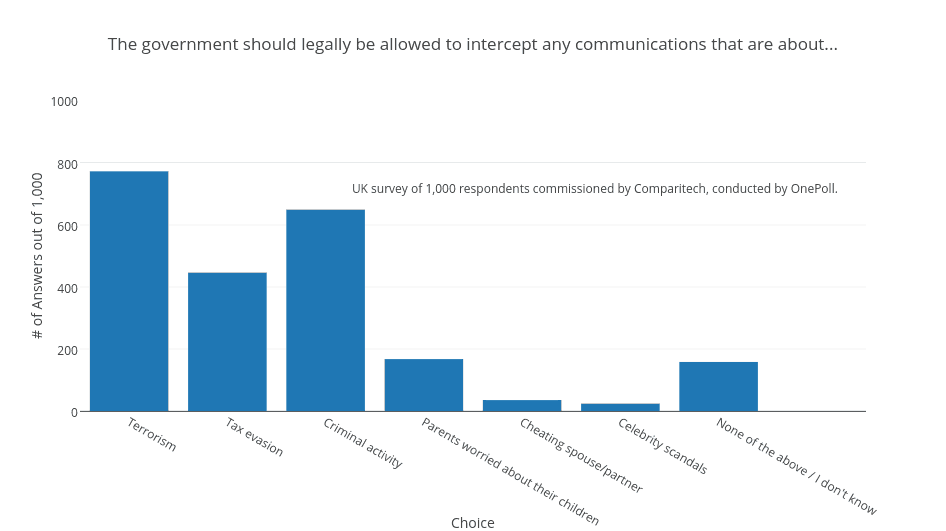

When asked in what scenarios the government should be legally allowed to intercept any communications, 77.2 respondents answered “terrorism”, and 64.9 percent replied “criminal activity”.

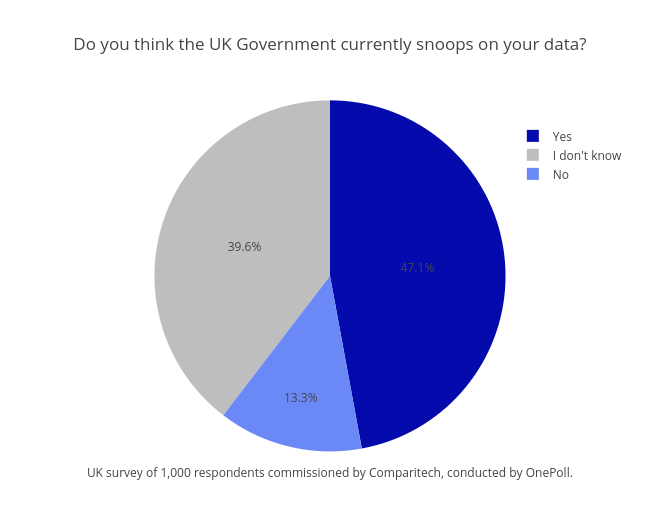

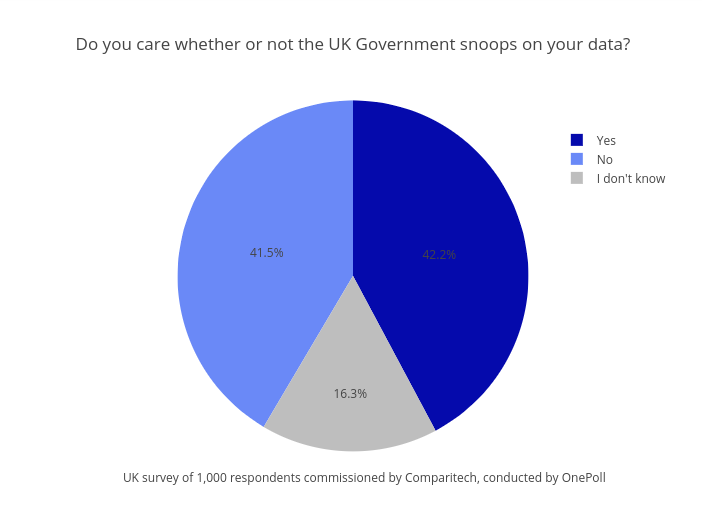

47.1 percent of the UK survey takers said they think the the government currently snoops on their data. 39.6 percent said they don’t know. 42.2 percent said they care if the government snoops on their data, while an almost equal number said they don’t care.

The Pew Research Center reports that Americans are generally more opposed to bulk surveillance than Brits, but still support the monitoring communication of terror suspects.

Bulk interception vs bulk interference

Bulk interception gathers information from a huge number of people, most of whom are not under investigation. The goal is to find a needle in a haystack. This differs from targeted interception, such as bugging a suspect’s phone or planting spying software on their computer.

Bulk interception also differs from bulk interference. While Anderson supported the interception of data, he was not so quick to back the bulk interference of devices, or hacking through malware, backdoors, and other means. According to his report, bulk interference has not yet been put into practice by British spy agencies.

Anderson expressed some reservations in his report about the government hacking of endpoint devices such as mobile phones and laptops. There might be circumstances in which an individual could mount a legal claim against the government, he notes in the report. Anderson argues there is a distinct, but unproven operational case for it.

A boost for the Snooper’s Charter

Anderson’s investigation was kept secret until the report was published. He was given access to details of operations by British spies in Afghanistan and other foreign territories.

The report could boost parliamentary support for the Investigatory Powers Bill, also called the “Snooper’s Charter” by privacy advocates. Prime Minister May responded to the report in a statement, saying, “Mr. Anderson’s report demonstrates how the bulk powers contained in the Investigatory Powers Bill are of crucial importance to our security and intelligence agencies.”

Anderson did not investigate another aspect of the Investigatory Powers Bill: the retention of internet records for 12 months–a major point of contention between Conservatives and Labour.