There’s no doubt that we live in a unique time in history; the dystopian science fiction world predicted by George Orwell and Aldous Huxley. If you are still in doubt, take a good look at your smartphone. This little but incredibly powerful tool has become so vital to our lives that we often take it for granted. It seems perfectly normal to pull it out of your pocket anywhere on the planet to carry out day-to-day tasks of communicating, socializing, keeping track of your health and finances, among others.

But we often forget or fail to realize that the smartphone is a double-edged sword. On the one hand, it grants us the ability to enjoy all of the above benefits and much more. But on the other hand, it can also serve as a powerful surveillance tool that poses an enormous security and privacy risk. Your smartphone tracks your location at every point in time—where you live, where you work, where you visit. As you move around with your phone, you are indirectly saying to your service provider, “I allow you to know where I am at all times, in exchange for the ability to make and receive calls”. This is inherent in how the service works. Tech companies such as Google, Facebook, Uber, Airbnb, Tinder, and a host of others use location services like GPS built into your smartphone to constantly track your location in order to deliver all sorts of location-based services to you. If you depend on those services, you’ll find it difficult to escape location tracking.

If the UN security council passed a resolution that required everyone to carry a tracking device, such a resolution would immediately be greeted with mass resistance. Yet we proudly carry our smartphones everywhere.

If the EU passed a law mandating all citizens to regularly notify it of “what’s on your mind”, citizens would not hesitate to rebel. Yet they happily notify Facebook all the time.

If the police department in your country obtained a court order demanding copies of all your daily email and instant message conversations, citizens would protest. Yet we provide copies to various email/IM service providers.

All this data accumulated can potentially be used to build an accurate profile of you, to predict and influence your future behavior, and can be sold to interested parties. This is what Harvard scholar Shoshana Zuboff calls Surveillance capitalism.

What is Surveillance capitalism?

Surveillance capitalism describes the monetization of personal data captured through monitoring of user’s online activities and behaviors. It’s a new economic order that, according to Zuboff, “claims private human experience as free raw material for translation into behavioral data”. These data are then analyzed to predict our behavior and sold as prediction products to business customers who can benefit from knowing what we’re likely to do.

It is the predominant business model of the internet. Under surveillance capitalism, we’ve lost control of our devices and personal data. The primary goal is personalized advertising. Advertising it seems was the only revenue model that made sense as people were unwilling to pay even a small amount for access to online services. Surveillance aided that revenue model and made advertising more profitable.

How do businesses use surveillance capitalism?

Despite giving away many services for free, internet companies are able to generate substantial profits through personalized advertising. Selling advertising is the largest source of revenue for many internet companies that offer free services. They use the data they collect about you to customize and deliver targeted advertising messages. The data Google has about your viewing habits on YouTube for example are used to embed targeted advertising directly into the video clips that you watch, as well as promoting featured content. In Android smartphones, Google and app developers use in-app advertising to cash out on your personal data. The data gathered about your usage of installed apps and other behaviors on the internet is sold to businesses interested in selling services to you, according to the secret profile they have of you.

By utilizing the vast amount of personal data from its 2.6 billion active users, Facebook can also tailor ads to suit your situation. Advertisers can target ads to you based on your religious or political preferences. If for instance you change your relationship status from “Single” to ‘Engaged’, you’re likely to see loads of wedding related ads.

It all started at Google back in the early 2000s when it accidentally opened Pandora’s box. The event quickly spread to other tech companies such as Facebook, Yahoo, Amazon, Microsoft, and a host of others. These companies capture surplus behavioral data and use it to produce prediction products that they sell to advertisers.

With their unique access to behavioral data, it is now possible for tech companies to determine what a particular individual at a particular time and place was thinking, feeling, and doing. All the free digital services they churn out are geared towards accumulating surplus behavioral data for commercial gain. They want your CV, pictures, videos, voice, internet searches, email/IM conversations, family life, buying behavior, brain waves, and even your vital signs. In fact, with the advent of COVID-19, we’re even likely to see more foray into biosurveillance. According to Yuval Harari, “if we are not careful, the pandemic might nevertheless mark an important watershed in the history of surveillance. Not only because it might normalize the deployment of mass surveillance tools in countries that have so far rejected them, but even more so because it signifies a dramatic transition from ‘over the skin’ to ‘under the skin’ surveillance”.

No doubt, surveillance capitalism and the digital age, in general, has brought tremendous benefits to society. It has revolutionized law enforcement, traditional commerce, products and services, and spawned entirely new categories of businesses. It has made life easier for people in all sorts of ways and will continue to do so in years to come. Nevertheless, the risks associated with surveillance capitalism are real, and our response has largely been passive.

Why do we permit companies to make money from surveilling us?

Because it is not that obvious, we tend to tolerate surveillance to a level that we would never allow in the physical world. We seldom think about all the bargains we’re making. But the reality is that we are perpetually being watched online by virtually everyone—big tech companies, advertising agencies, hackers and the government. In autocratic countries, surveillance is used by the government for social control. In capitalist countries, it’s used by tech companies to influence our buying behavior, and is incidentally used by the government. Tech companies harvest all sorts of data about us from our devices and online activities, often without our consent. It’s so stealthily done that you rarely get to experience the creepy feeling of being watched. Because we don’t get to see how this plays out in reality, we often fail to appreciate the enormity of the risks.

How would you feel if you suddenly realize that you are being followed around by over ten salespersons in a store? They take record of how much time you spend in each aisle, which items you looked at and which ones you ignored, and the ones you finally ended up buying. Or, imagine meeting a smart guy who offered to digitize all your valuable documents, notebooks, private records, diary, audio and video tapes, and store them in a secure online server where you can easily access them anywhere in the world. All for free. All you have to do is to agree to a seemingly simple 30-page contract full of confusing legalese. Part of it says that in exchange for the wonderful free service, you grant him “permission to access and process your digital assets, including a worldwide license to host, use, modify, copy, translate, transfer, distribute and create derivative works” of your digital assets. Buried in the agreement is another clause that states that he can “change, suspend, or discontinue the service at any time without notice, and may amend any of the agreement’s terms at his sole discretion by posting the revised terms on his website”. Your continued use of the service after the effective date of the revised agreement constitutes your acceptance of its terms. And because you’re in a hurry and urgently in need of your documents in digital formats, you agree and accept the contract terms, even though you don’t really understand it.

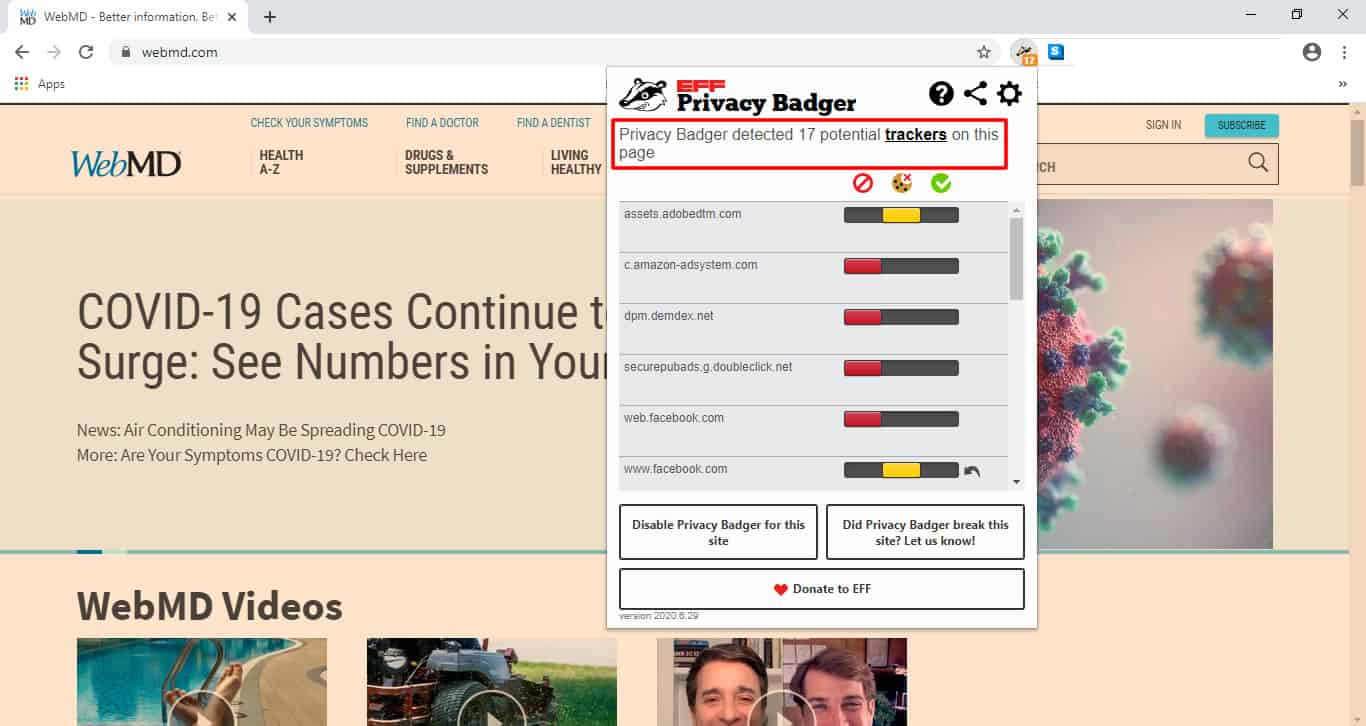

Unfortunately, this is the everyday experience of most people on the internet. I recently visited a popular healthcare information website and found about 17 trackers watching me as I moved around the site (see Figure 1.0 above). This is akin to 17 salespersons following me as I move around in a shop. Surveillance capitalists don’t come to us pointing a gun on our heads and making demands. They come to us in the form of the free services we innocently sign up for, not realizing that “free” is indeed a special price.

We use systems that spy on us in exchange for free services. By virtue of the free services you consume, Google for example gets to know who you are, where you live, where you work, where you’ve traveled, the kind of YouTube videos you like to watch, your most frequently visited website, and much more. Similarly, Facebook also knows virtually everything about you: your birthday, wedding anniversary, family life, likes and dislikes, religious and political views, and a host of others. You’re more likely to fall prey if you are ignorant or oblivious to the dark world of surveillance; or if you depend so much on free services—low income earners are especially vulnerable because of their dependence on free digital services.

People don’t bother to read privacy policies before rushing to agree to the terms of service. Even people who do read privacy policies struggle to understand them because they are usually crafted to make it uninteresting to a regular user. It’s therefore not surprising that so many of us rush to sign up for free digital services; we thought that they regard us as the customer, but now we understand that the surveillance capitalists behind those services regard us as their free raw materials and/or the product. We thought that we know by searching Google, but now we understand that Google uses our searches to know us. We thought that we use Facebook to connect, but now we understand that connection is how Facebook taps into our minds. We thought that “privacy policy” meant “privacy protection”, but now we understand that privacy policies are actually surveillance policies.

Impact on individuals, society and culture

The risks from surveillance capitalism are many, and the costs to individuals and society as a whole arguably outweigh the benefits. It renders humans as hackable entities, usurps decision rights and individual autonomy (free will) that are essential to the functioning of a democratic society.

Now, a social media platform can potentially distort public opinion by amplifying the voices of people it agrees with, and dampening those it doesn’t. The internet you see is increasingly tailored to the profile the tech companies have of you, thereby creating the impression that your narrow self-interest is all that exists. Typical examples include Google personalized search results and Facebook’s personalized news feed. This is what internet activist Eli Pariser described as “filter bubble”. At first it may seem like a good idea, but on a large scale, it’s harmful to both individuals and society, in the sense that they have the possibility of “undermining civic discourse” and making people more vulnerable to “propaganda and manipulation.” No one wants to live in a society where everybody is isolated in their own cultural or ideological viewpoints, where we never have spontaneous encounters that inspire, educate and challenge our views.

Everything we do on the internet is permanently recorded and saved in ways we have no control over. This facilitates control. Most of the tech giants involved in surveillance capitalism know us better than we know ourselves. This unequal knowledge about us confers on them unequal power over us. It wasn’t always like this. Throughout most of history, our interactions and conversations have been largely ephemeral. Now the internet never forgets; but we still behave as if it does, as if our interactions were ephemeral. As Bruce Schneier puts it, “forgetting is an important enabler of forgiving. I’m not convinced that my marriage would be improved by the ability to produce transcripts of old arguments”.

What can you do about it?

One of the ways you can personally defend yourselves against surveillance is by arming yourself with knowledge and altering your behavior based on that knowledge. How about minimizing your use of free digital services, and taking advantage of premium alternatives, where possible? How about shunning apps that spy on you, or apps that ask for excessive permissions that are not necessary for their primary function? How about turning off location services on your smartphone when you don’t need it?

There are also various privacy and anonymity technologies you can use to protect your data and online identities. DuckDuckGo for instance is a search engine whose business model does not revolve around tracking its users. Proton Mail is an email service whose business model does not depend on mining users’ data; rather it uses client-side encryption to protect email content and user data. Ello is an ad-free alternative to existing social networks. They may not be as popular as the big names, but they are viable alternatives if you want to lower your risk of exposure to surveillance. There are browser plugins that you can install to monitor and block sites that track you as you browse the Internet. Among them are: TrackMeNot, Disconnect, Privacy Badger, Ghostery, and others. The best tool available today to protect your anonymity when browsing the internet is the Tor browser. In fact, when combined with a reliable VPN service (Tor over VPN), it offers a double dose of anonymity and privacy.