Apple’s Private Click Measurement (PCM) gives websites a way to measure the effects of advertising. It’s designed to replace the ubiquitous third-party cookies that secretly harvest our data, but is it actually any better for privacy? We find out.

What is PCM and why is it necessary?

The majority of “free” websites that most people use on a daily basis are paid for through advertising. Websites can host adverts and get paid for it. However, advertisers want to know that they’re getting their money’s worth. This requires some way of knowing when a user has clicked on an advert, and then bought (or signed up to something) on the advertiser’s site.

Traditionally, this was achieved by putting cross-site tracking cookies in site visitors’ web browsers. These “persistent” cookies are notoriously bad for privacy, enabling all manner of third parties to collect data about people’s online activities to share, sell or otherwise exploit for financial gain.

The good news is that third-party cookies are on the way out. The Safari and Firefox browsers already block them by default, and Google is phasing them out for 1% of Chrome and Android users in the first quarter of 2024 with full deprecation by the end of that year.

With PCM, Apple is joining other big names such as Microsoft and Google in attempting to create an alternative that satisfies advertisers’ needs without sacrificing user privacy. PCM allows for ad-click attribution, while not allowing arbitrary cross-site tracking.

How does PCM work?

PCM is already enabled in Safari and iOS through an in-browser API. It counts how frequently users click on ads and subsequently purchase a product, or perform some other action, on the linked site. Advertisers can use this data to judge how well an ad campaign is performing.

However, according to marketing company Louder: “Demographic, geographic and or device type breakdowns will no longer be supported for conversion reporting.” This, it says, will make campaign optimisation “more difficult, since you won’t be able to slice and dice conversions as easily as before”. So while the options for creating highly targeted ads will diminish, websites with successful conversion rates will likely continue to receive ad company business.

The PCM process proceeds according to the following simplified outline:

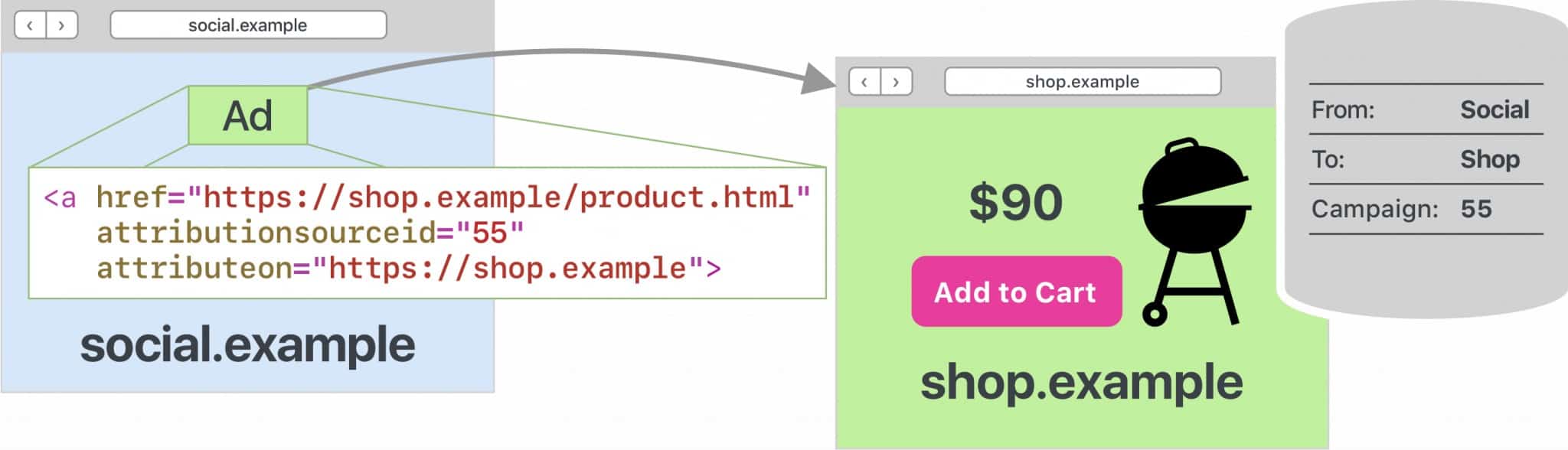

1. A user is browsing the social.example site and sees an ad for a barbecue that they like the look of.

2. This ad contains a link to the shop.example site. The link HTML also contains an 8-bit attribution source ID and the address of the click destination website that wants to attribute incoming navigations to clicks (“attributeon”).

3. If the user clicks the link and arrives at the “attributeon” website, the “attributionsourceid” is silently stored in the user’s browser as a click from social.example to shop.example for 7 days.

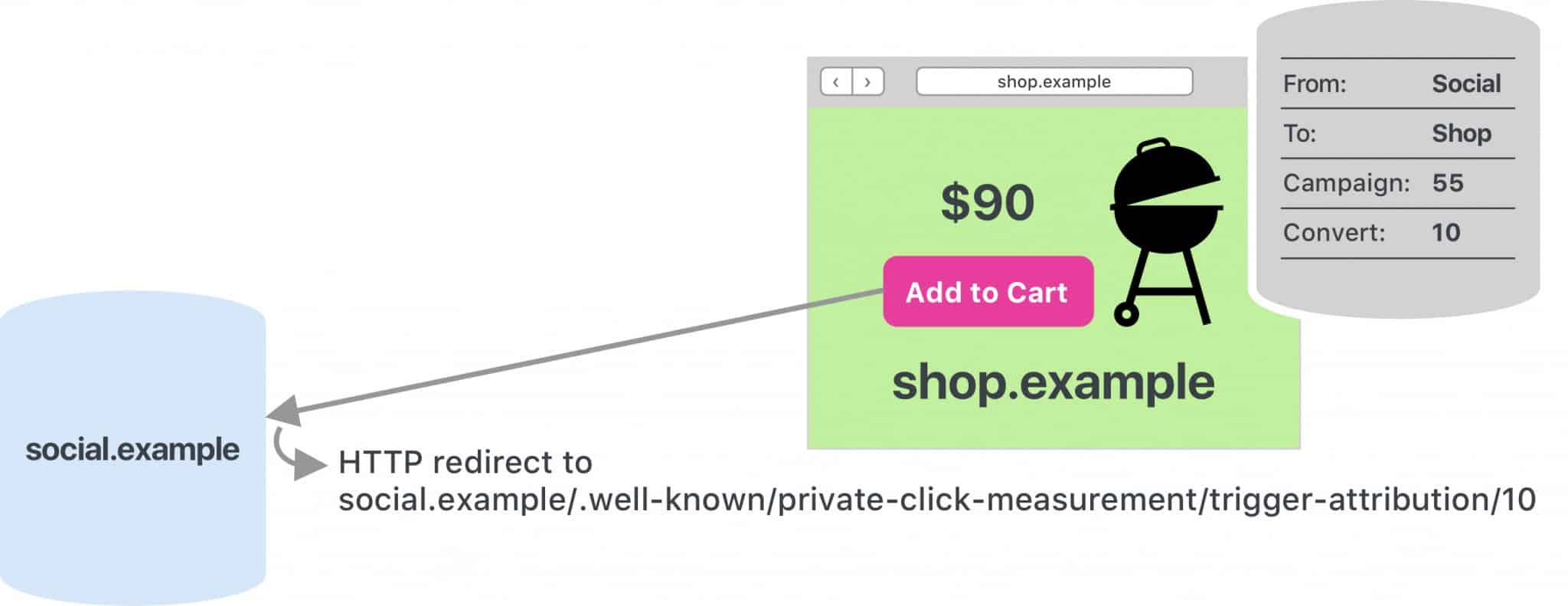

4. The user’s activity while on this site can lead to a triggering event (e.g. if they buy something). This leads the “attributeon” website to make a HTTP GET request to social.example. It is this GET request that triggers attribution. The request includes a four-bit decimal value that encodes the user action that triggered the attribution (trigger data), an optional 6-bit value for allowing multiple triggering events to result in a single attribution report.

5. The browser then checks for relevant stored clicks. If there’s a match, it schedules a single attribution report to be sent out at some point within 48 hours.

6. Reports are sent as HTTP POST requests and include: the click source website, the 8-bit source id, the attribution destination website, and trigger data.

In essence, the user’s browser creates a report when clicks and subsequent purchases (or other desirable actions) occur. PCM limits the information included in the report, submits them to the websites through an anonymization service, and only after a delay of one to two days.

In many ways, yes. The delay in sending an attribution report helps prevent it being matched to the event that triggered it – as does sending it via an anonymizing proxy (Apple’s Private Relay).

By limiting the availability of identifiers, PCM intends for multiple users to have the same identifiers – thus increasing an individual’s anonymity. When a user clicks on a link, it can be assigned one of 256 identifiers. If they click to buy something (or perform some other action that creates a trigger event), it can be assigned one of 16 identifiers. The small number of allowed identifiers acts as a further privacy safeguard.

However, PCM is far from perfect. Mozilla carried out a detailed analysis of PCM and concluded that, although PCM “prevents sites from performing mass tracking, it still allows them to track a small number of users”.

For example, the delays in sending reports are only useful if there are a large number of them being generated. It could be possible to match reports to events if there was only one in a 24-hour period, for example. By the same reasoning, sites may be able to more easily identify users who are active at unusual hours.

The Mozilla analysis also describes how a pair of sites could agree to track a particular user. For example, a user that generates a report on one site could be shown a link to a second site where they generate a second report. If these reports arrive within two days then it could be inferred that they came from the same person. However, the report’s author admits that “confirming a guess about user identity across sites is unlikely to be feasible for many sites.”

Conclusion

PCM is a vast improvement on traditional third-party cookies. The limited availability of identifiers makes it far less feasible for sites to identify individual users who have clicked on an advert. However, as Mozzilla pointed out, it is not impossible. “PCM does not provide users with any guarantee that sites are unable to use the information it provides for tracking,” it says.

Limiting the data collected by third parties while also providing advertisers with what they need to keep functioning is no easy task. Just ask Google. It first announced its plan to make “third party cookies obsolete” back in 2020. Almost four years later, it’s just beginning to implement its Protected Audience API.

Designed to let ads be targeted without sharing users’ browsing history, the Protected Audience API has been criticized for being as bad for privacy as the third-party cookies it’s supposed to replace. Ad-blocking software company, AdGuard, says that the API turns the “browser itself into an instrument to show ads, an ad auction tool of its own kind”.

Related: