Egypt has a young, tech-savvy population, and the internet is widely used for business and socializing. However, over the past decade, successive governments have been nervous about the population’s activities.

The turning point in the openness of Egypt occurred in 2011, when a popular uprising, known as the Arab Spring, occurred. This popular movement caused the downfall of President Mubarak, with demonstrations organized through social media. In an attempt to block this insurgence, the Mubarak regime shut down the internet. However, their actions were too late, and the government fell. The new government and all successive administrations have become progressively more suspicious of the power of the internet. While political insecurities continue, control over internet access tightens.

Like many developing nations, Egypt’s elders want the economic growth that the internet can bring. Still, they don’t want to let information and influence from the outside world erode traditional values.

Internet penetration and availability

The Datareportal Digital 2021 Report, compiled by Hootsuite, identified an internet penetration rate of 57.3 percent in Egypt. Those figures were collected in January 2021, and they revealed that the number of internet users had increased by 4.5 million over the past year. This increased Internet penetration by 8.1 percent to a total of 59.19 million users. This is out of a total population of 103.3 million.

In comparison, chaotic Libya to the West has an internet penetration rate of 56.2 percent, giving a total of 3.19 million users out of a total population of 6.91 million. To the East, Israel is a highly advanced cybersecurity powerhouse with a very high internet penetration rate of 88 percent, which means 7.68 million users in a total population of 8.72 million.

Although Israel has more advanced technology and greater uptake of the Web, the enormous population of Egypt dwarves all of its neighbors, this makes the country, potentially, a very lucrative market for eCommerce. In short, Egypt is a very influential market, and the encouragement of internet uptake would bring the Egyptian government leverage in trade negotiations and peace plans. There is a big incentive to other countries in the Middle East to maintain a positive image among Egyptian consumers.

Working with figures from July 2020, supplied by Cable.co.uk, Egypt’s internet prices are reasonable compared to nearby nations. The average cost of Broadband packages in the country was $17.83 per month, with the cheapest plan available costing $6.05 per month.

Looking at other nations in the Middle East and North Africa, Tunisia has a much cheaper Broadband market with an average price of $11.65 per month and the most affordable plan there costing only $2.90 per month. However, the story is entirely different in Libya, which lies between Egypt and Tunisia. The average price for Broadband there is $70.67 per month, and the lowest price is $18.60.

The average monthly household income in Egypt in 2021 is $382.14. So, the typical cost of a home internet service is well within the means of a typical family.

There are about 361,000 free WiFi hotspots in Egypt, according to WiFi Map. These free access points are evenly spread around the country. Unlike many developing economies, where almost all of the accessible WiFi locations are in the capital, Cairo has a little over 64,000 points, about 1/6 of the total for the country.

Internet speeds in Egypt

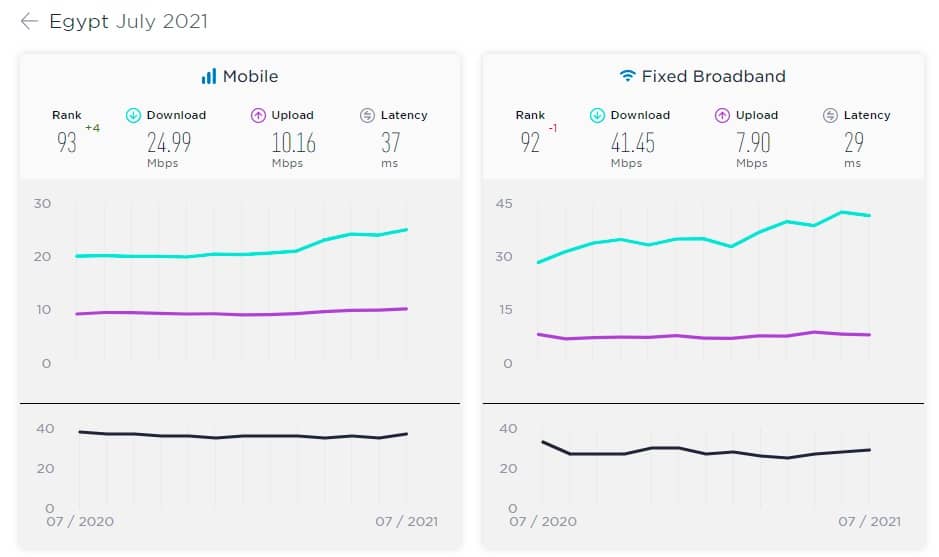

Ookla runs the Speedtest Global Index, which tests the internet speeds in 180 and publishes the average for each month. Egypt’s internet speeds put it at 92 on the list for fixed-line Broadband with a speed of 41.45 Mbps. The average mobile internet speed in the country was 24.99 Mbps on average in July 2021.

For comparison, Monaco has the fastest average fixed-line Broadband speed at 256.7 Mbps, and the UAE has the fastest mobile internet with 190.33 Mbps. Israel has an average fixed-line Broadband speed of 168.23 Mbps and a mobile internet average speed of 46.3 Mbps. Libya’s internet is much slower than that available in Egypt, despite its higher price. The average fixed-line internet speed is 16.31 Mbps, and the mobile internet speed is 17.41 Mbps.

Fixed-line connections in Tunisia are prolonged, with an average speed of 9.45 Mbps. The performance of the mobile internet is better, with an average speed of 30.8 Mbps. The USA’s positions in those tables are in 14th place for mobile speeds at 91.01 Mbps and 14th for fixed-line broadband speeds at 195.55 Mbps.

Digital awareness

According to the Global Cybersecurity Index 2020, prepared by the International Telecommunications Union, Egypt is very advanced in its cyber security awareness. The country is ranked in 23rd place globally for its defenses against possible attacks. The government’s Ministry of Communications and Information Technology is in charge of the national cyber defense plan.

The most closely involved in the daily management of national cybersecurity activity is the Egyptian Computer Emergency Readiness Team (EG-CERT), which was established in April 2009. EG-CERT acts as the government’s response team and monitors and reports on nationwide cybersecurity readiness, and communicates threat intelligence.

Online anonymity

The Egyptian government’s public surveillance activities are one of the reasons that the country scores poorly with Freedom House’s Internet Freedom scores. The other factor is government restrictions on Web availability and internet openness.

The government has taken steps to disable secure messaging systems. For example, Signal, the encrypted messaging app, monitors are not available in Egypt due to interference by government agencies. The government also uses the services of the Hacking Team, an Italian company that provides surveillance tools.

The SSH protocol has not been available to protect communications in Egypt since 2016. SSH provides security for SFTP, the Secure File Transfer Protocol, which is widely used in the international business community to protect data transfers.

The inaccessibility of such encryption systems is aimed at removing the secrecy used by terrorists in their communications. However, this situation makes it difficult for businesses to fulfill their obligations to data privacy, making personal online anonymity very difficult to achieve.

All international internet traffic passes through two government-controlled points, and the intelligence agencies of Egypt apply automated detection methods to this traffic, much like the practices of Chinese authorities with their “great Firewall of China.” More worrying, periodically, HTTPS has been blocked by the Egyptian government. This protocol protects Web transactions and is the primary security system that gives consumers the confidence to make online payments with their bank cards. Threats to this security system hamper the growth of eCommerce in the country.

Although the removal of HTTPS facilities in Egypt has not been permanent, intermittent interference with this and other online privacy mechanisms shows that, from time to time, the government’s desire to combat insurrection and terrorism outweighs its hopes to foster a digital economy. When faced with a choice between international standards of liberty and the need to enforce national security, the Egyptian government always comes down on the side of more controls on internet access and blocks anonymity wherever possible.

Access to privacy tools

VPNs are not illegal in Egypt. However, the government blocks access to the sites that advertise these services and other sites that promote them. Readers in Western nations shouldn’t look upon this as draconian or exceptional, however. Many “advanced” and “open” democratic governments impose similar controls. For example, Virgin Media and other ISPs in the UK regularly block access to VPN websites and sites promoting VPNs.

As with those UK restrictions on VPN access, the Egyptian controls on the use of virtual private networks are implemented with subtlety. Instructions are given to ISPs behind the scenes and blocks are implemented by simply “blackholing” sites through tampering with their domain name service entries. This makes it impossible for regular users to reach those sites. Technically, however, those sites are not banned, no government pronouncement is needed, and no laws need to be implemented. The sites of TunnelBear, CyberGhost, and Hotspot Shield are among VPN websites that are blocked in Egypt.

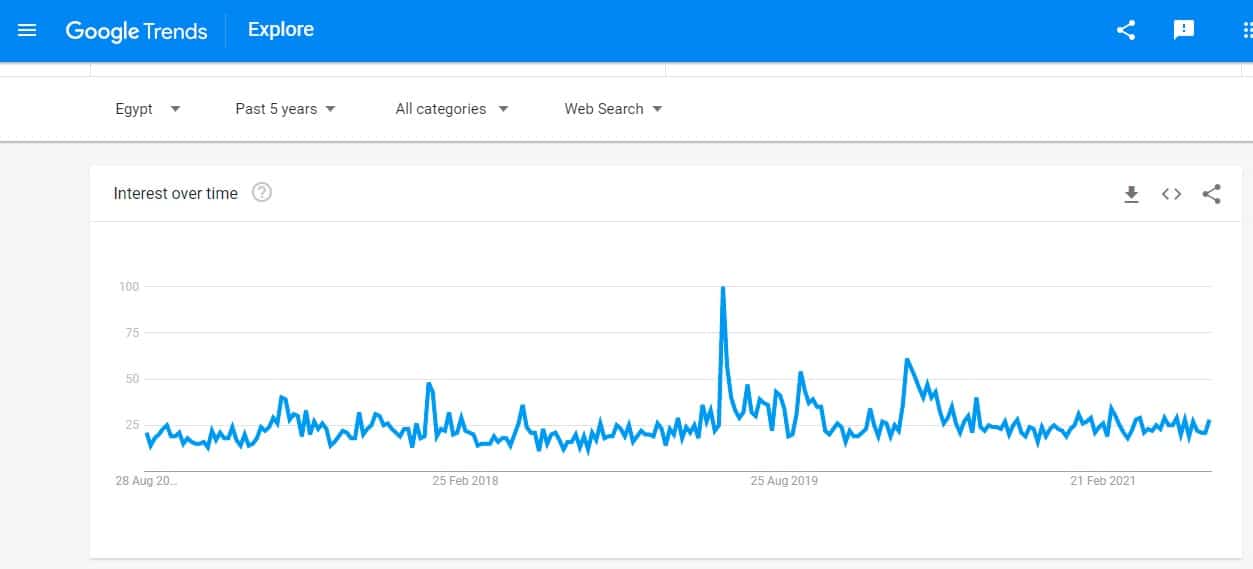

The Egyptian government’s control over information about the existence of VPNs has been very successful. The graph below shows the search engine traffic for information about VPNs from Google over the past five years.

There is a marked spike in queries about VPNs in May 2019. This is probably because independent media was severely restricted in April 2019, and information about these measures did not emerge until they were lifted. In addition, sudden knowledge of the recent crackdown probably drove many Egyptians to look for ways to circumvent such campaigns in the future.

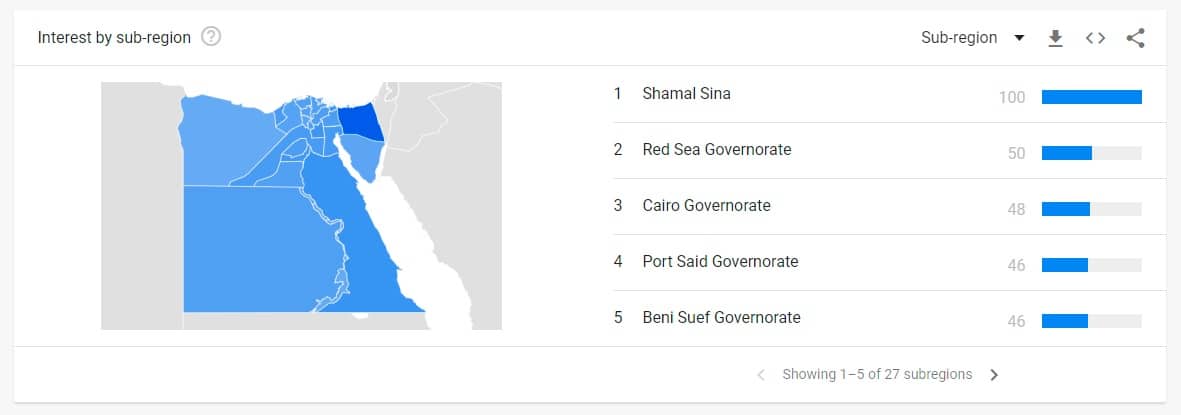

A look at the map of Egypt provided by Google Trends with the locations of searches for VPN information shows that the North Sinai area has the most activity.

The North Sinai region, called Shamal Sina, borders Palestine and Israel and is intense terrorist activity and military actions.

The Tor browser is a free privacy system that is similar to a VPN. While there is awareness of this service in Egypt, it is not widely known in the general population. As with other privacy systems that employ encryption. Tor has been interfered with, and its transmissions have been blocked within Egypt by the government. However, a graph of accessing users of Tor from August 2020 to August 2021 shows that the system is currently operating.

Apart from a one-day surge of users in November 2020, the daily user count of Tor in Egypt is usually just below 5,000. For comparison, the number of users in the USA was around 500,000 per day.

Cybercrime: prevalence and attack types

Egypt is engaged in several disputes with neighboring nations, and this is the source of most of the cyber attacks in the country. In most cases, the Egyptian government is the target for incoming cyberattacks. Although the government of Egypt does not officially run special cyber operations against its enemies, there have been a number of conveniently timed hacker attacks against countries with which Egypt is in dispute – most notably in 2020 when the Ethiopian government was hacked by Egyptian hackers during a period of dispute between the governments over the creation of the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam.

Blocked content

Like many Middle Eastern governments, Egypt’s leaders focus their control of Web content on blocking opposing views and permissive social attitudes. Blocks on foreign and independent news sources increase during politically important events, such as elections or referenda. Social media systems get controlled when mass movements or pressure groups appeal to public sympathies.

Apart from total periodic bans on such news outlets as The New Arab, The Egyptian authorities have developed the ability to block specific pages or even sections of pages or images, while allowing the rest of the site’s content to be transmitted.

The blocks seem to occur through several methods. A block on a site can also knock out access to all other websites, or parts of sites that are hosted by the same content delivery network (CDN). Interference that performs a type of redaction is committed instream. This is probably implemented at the same points that the government’s surveillance takes place through deep packet inspection.

The government’s national firewall seems capable of extracting and even replacing selected content as it passes through its proxies. It is even able to inject advertisements and malware into a delivery transfer.

VoIP and secure chat systems are periodically blocked to create a disruption in the reliability of these services and discourage their use. This has a double benefit for Egypt’s government who dislikes the protection from snooping that encrypted chat systems afford and also wants to discourage free telephone systems.

The government doesn’t want to erode the profitability of its own telephone service. The main telephone company in the country is Telecom Egypt, which is 80 percent government-owned. Expensive international calls drive the business’s profitability and free international calls from VoIP systems, erode that income stream.

Site with sexual content and those that promote LGBT rights are regularly banned. According to Masaar Technology and Law Community, 606 websites are currently blocked in Egypt. Of those, 352 relate to VPNs and other online privacy services and 24 are pornography sites.