Governments and private companies around the world are launching apps and websites to help inform the public and prevent the spread of COVID-19. Many of these apps collect users’ personal information, health status, and location history in order to better track how the spread of COVID-19 is advancing.

Comparitech examined more than 100 of these apps from over 40 countries to find out whether they’re catching on and what risks they might pose to users’ privacy.

Coronavirus-related apps come in a few different varieties. They include features such as:

- Contact tracing, such as maps of known nearby infections

- General information, news updates, and alerts

- Quarantine enforcement

- Symptom checkers and self-diagnosis

- Remote interaction with medical professionals

Coronavirus Apps & Websites

| Country | City/Region | App/Website/Technique Name | Developed For | Description | Data Required | Privacy Policy | # of Downloads | Ranking in App Store |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Afghanistan | Coronavirus Tracker | Government of Afghanistan | Live map Symptom checker Case reporter General information | - Name - Telephone # - Location - Symptoms | No privacy policy listed. | Web-based | Web-based | |

| Argentina | Covid-19 Ministerio de Salud | Ministry of Health of the Nation | Symptom checker | - Symptoms - Age - Passport # or DNI - Telephone # - Address - Location | Users have to give their consent for the "Secretariat to transfer the User's personal information collected by the Application to other state entities and / or health facilities so that they can contain and / or mitigate the spread of the COVID-19 virus, help prevent the over-occupation of the Argentine health system and for any other purpose related to the emergency caused by the pandemic." | 500,000 | #2 in Medicine | |

| Argentina | General Pueyrredón | Testeate MGP | Municipalidad de General Pueyrredon | General information Test request | - Name - Age - DNI - Symptoms - Travel History | Not clear. | 1,000 | N/A |

| Argentina | Mendoza | CoTrack | Government of Mendoza | Symptom checker Location tracker General advice | - Symptoms - Geolocation - Telephone # (Website) - Gender (Website) - DOB (Website) | All location data is anonymized and does not leave the device. Any location data provided by the Ministry of Health is also anonymized before being used in the app. However, if using the website, more information is required. | 5,000 | N/A |

| Armenia | Covid-19 Armenia | Government of Armenia/Ministry of Health | General information Symptom checker | - Name - Phone # - Address - GPS Location - Camera | Locations identified by the user may be used to identify locations of coronavirus infections. Full access to camera is required. | 1,000 | #1 in Medical | |

| Australia | Coronavirus Australia | Australian Department of Health | Symptom checker General advice Live map | Data is stored until they "no longer need for the purpose it was collected." | 500,000 | #1 in Health and Fitness | ||

| Australia | WhatsApp Channel | Australian Department of Health | Information updates | |||||

| Australia | Snewpit | CKG Projects Pty Limited | Live map News updates Contribution features | - Name | Some personal data collected and IP addresses. Personal information may also be used "for ancillary purposes such as locating and identifying users." Personal information may also be used alongside log data before being aggregated. Information is destroyed when it is no longer required. | 50,000 | #106 in Social Networking | |

| Austria | Stopp Corona | Red Cross (Austria) | Location tracker Notification of contact with coronavirus cases Symptom checker | - Phone # - Bluetooth - Microphone | All of the user's data is anonymized and the Red Cross will not use the data. However, if a user is diagnosed, a cell phone number is requested. Users can also submit messages to those in the app if they are diagnosed with the disease (but they remain anonymous). | 100,000 | #1 in Medicine | |

| Bhutan | StayHome | Ministry of Health and Royal Government of Bhutan | Quarantine tracker General information Symptom checker | - Name - Email Address - Physical Address - Phone # - Selfies | General privacy policy from 2017. Not entirely clear how information may be used. | 0 | #5 in Health and Fitness | |

| Bolivia | Coronavirus Bolivia | Government of Bolivia | General advice | No privacy policy listed. | 10,000 | #1 in Medicine | ||

| Brazil | Coronavirus SUS | Government of Brazil | General advice Symptom checker Map of health units | No clear privacy policy. | 1,000,000 | #3 in Health and Fitness | ||

| Brazil | Cachoeirinha | Cachoeirinha ContraCoronavirus (Contra o Coronavirus) | Municipal of Cachoeirinha | Symptom checker Live map Submit cases | "6.3 By sending information you will be contributing to measures to combat the coronavirus; 6.4 You agree that upon reaching the clinical limit according to information sent, a medical team may go to your address provided for removal and referral to specialized care." | 500 | Not ranked | |

| Brazil | Paraná | COVID19 Paraná | Government of Paraná | QR code | - Name - DOB - ID # - Mobile # - Email Address | Not clear. | 1,000 | Not ranked |

| Canada | British Columbia | BC COVID-19 Support | Ministry of Health BC | General advice Information updates Symptom checker | "Thrive Health will only use the personal information it collects for purposes related to supporting the Ministry of Health in managing COVID-19, and will not disclose or retain your personal information for any other purposes." Data is anonymized to provide population health data to the Ministry of Health. | 10,000 | #11 in Medical | |

| Canada | Hamilton, Ontario | COVID-19 Community Watch App | The Hamilton Academy of Medicine | Symptom checker Surveys | - City - Postcode - Province - Gender (optional) - Ethnicity (optional) | No personal data or survey information is saved on the mobile. Raw data is shared with authorized members of the medical community or public institutions. Personal information (e.g. addresses) will not be shared unless there is an absolute necessity (and not to the general public). | 50 | Not ranked |

| Canada | Canada COVID-19 | Government of Canada | General advice Information updates Symptom checker | - Age - Postal Code - Device Location | "Thrive Health will only use your personal information for purposes related to supporting Health Canada and your province in managing COVID-19, and will not disclose or retain your personal information for any other purposes." | 50,000 | #1 in Medical | |

| China | Alipay/WeChat | Chinese Authorities | Location tracker Health code QR code scanning | - Identity Details - Device Location | Vague and unclear. | 5,000,000 | #2 in Life | |

| Colombia | CoronApp-Colombia | Government of Colombia | General information Symptom tracker | - Name - Gender - DOB - Email Address - Physical Address - Symptoms - Travel History | Listed policy is for another app but states: "We use this information to improve, qualify and organize health actions based on participatory surveillance strategies, which consist of community participation in epidemiological surveillance actions. The collected data will be analyzed from a database anonymised by the statistical software of the epidemiological surveillance team." | 1,000,000 | #1 in Health | |

| Cyprus | CovTracer | RISE Research Centre of Excellence | Location tracker Time-stamped logs | -GPS | Data not accessible outside the user's device but users can export their locations. | 100 | N/A | |

| Czech Republic | Mapy.cz (New Feature for Coronavirus) | Seznam.cz a.s. | Location tracker Live maps | - Name - Email Address - Gender - Location | "If you turn on location sharing in your app because of COVID-19, we will process your location history and in the future we will be able to alert you if we find that you may have come in contact with a positively tested individual. All data is collected anonymously, we only save the app ID with no connection to your associated Seznam account or any other data. The data is saved separately from others and will be deleted after the epidemic is over. We do not share data with any other subject, any data sharing would require your explicit agreement." | 229,000 | #1 in Navigation | |

| Czech Republic | COVID-19! | Nemocnice Milosrdnych bratri, p.o. (The Brothers of Charity Hospital, p.o. in Brno) | General information News updates Case figures | The app may gather log files but this isn't connected to any PII. | 10,000 | #4 in Medical | ||

| Ecuador | SaludEc | Government of Ecuador | Symptom checker | - ID number - Physical Address - Geolocation - DOB - Gender - Marital Status - Contact Information - Symptoms/Diagnosis | Users are consenting to this data being used. No further instructions on how, where it is stored, or who may access it. | 100,000 | #1 in Medicine | |

| France | Paris | Covidom | Public Assistance-Hospitals of Paris (AP-HP) | Symptom checker Remote monitoring of patients Registration by a doctor is required | - Name - Telephone # - Email Address - DOB - Gender | Doctors are given access to the data. Data collected is kept for 10 years after the patient's death or 20 years from their last stay in a healthcare establishment. | 10,000 | #9 in Medicine |

| France | MaladieCoronavirus | Ministry of Health BC | Symptom checker | - Symptoms | Data is stored for 48 month and may be used for epidemiological studies. No PII data requested. | Web-based | Web-based | |

| France | Marseille | Epidemic Protect | Symptom checker | - Postcode - Age - Gender | No privacy policy listed. | Web-based | Web-based | |

| Georgia | Stop Covid | Ministry of Internally Displaced Persons from Occupied Territories, Labor, Health and Social Affairs of Georgia | Contact tracer Location tracker | - GPS - Bluetooth - Phone # | Anonymous user IDs are created and no sign-up required. Data may be stored for 3 years. | 50,000 | #10 in Medical | |

| Germany | VirusAssist | Healthcare X.0 GmbH | General information Live map | - Name - Telephone # - Email Address - Physical Address - DOB - Mobile Phone ID, IP address of computer | Information may be shared with third parties like service providers and other parties when required by law. | N/A | #23 in Health and Fitness | |

| Germany | CovApp | Charité | Symptom checker | - Symptoms | All data is collected anonymously. | Web-based | Web-based | |

| Germany | Corona-Datenspende | Robert Koch Institut | Smartwatch app Symptom checker | - Fitness bracelet/smartwatch - Postcode - Age - Sex - Height - Weight | Data processed anonymously. | 100,000 | #6 in Health and Fitness | |

| Guatemala | Asistencia COVID-19 GT | Oxfam International | Symptom checker General information Submit cases | Nothing required. Can voluntarily submit name of person with symptoms. | No names are published if submitted with cases. Data may be shared with third parties. | N/A | #17 in Reference | |

| Hong Kong | StayHomeSafe with Wristbands | Government of Hong Kong | Quarantine checker Location tracker (inc. wristbands) | - Name - Mobile # - Physical Address - Geolocation | Data will be used by the Department of Health to prevent the spread of the disease. The data may also be transferred to government departments. | 10,000 | #6 in Health and Fitness | |

| India | Goa | Test Yourself Goa | Government of Goa | Symptom checker | - Name - Mobile # - Postcode - IP address/geolocation | Data may be shared with third parties. | 50,000 | N/A |

| India | Gujarat | SMC COVID-19 Tracker | Government of Gujarat | Quarantine checker Location tracker | - GPS Location (every hour) - Questionnaire (twice daily) - Selfie (twice daily) Except between 9 PM and 9 AM | No privacy policy detailed but all information shared with the government. | Web-based | Web-based |

| India | Karnataka | Quarantine Watch | Government of Karnataka | Quarantine checker | - Personal details - GPS Location (every hour) - Selfie (every hour) Except between 10 PM and 7 AM | No privacy policy detailed but all information shared with the government. | 10,000 | N/A |

| India | Karnataka | Corona Watch | Government of Karnataka | Live map (inc. where people are in quarantine and their travels over the last 14 days) Location tracker | - Name - Mobile # - Physical Address - Gender - GPS Location | Addresses of specific people (i.e. those quarantined) aren't revealed. However, other PII data is collected and may be shared with the government | 100,000 | N/A |

| India | Kerala | GoK - Direct Kerala | Government of Kerala | General information News updates SMS notifications (daily) | The app is also used by the government as a source of information during the outbreak. PII and location may be shared. | 100,000 | #21 in News | |

| India | Maharashtra | Mahakavach | Maharashtra State Innovation Society in conjunction with the Nashik Municipal Corporation | Contract tracing Recommended to users by doctors/healthcare workers Quarantine tracker | - Name - Mobile # - Photos | Privacy policy states that third party services may collect PII. Information shared with the Health Administration. | 10,000 | N/A |

| India | Mumbai | BMC Combat Covid-19 | Municipal Corporation of Greater Mumbai (BMC) | Quarantine tracker | - Location | Privacy policy links to the website's privacy policy so it is unclear. App description does say that users' locations may be traced even when the app isn't open. | N/A | #67 in Medical |

| India | Nagaland | Self Declaration COVID-19 Nagaland App | Government of Nagaland | Location tracker Quarantine tracker | - Compulsory for those who have entered the state after March 6 - Name - Mobile # - DOB - Age - Gender - Husband Name - Email Address - Physical Address - GPS Location | Not clear what happens to the data but does state that third-parties may have access to personal information. | Web-based | Web-based |

| India | Puducherry | Test Yourself Puducherry | Government of Puducherry | Symptom checker | - Name - Mobile # - Postcode - IP address/geolocation | Data may be shared with third parties. | 10,000 | N/A |

| India | Punjab | COVA Punjab | Government of Punjab | Symptom checker General information | - PII - Location | Privacy policy states that "Your personal, demographic, location, device and other similar information may be collected." This information is used for analysis, statistics, and service improvements. Personal data is shared but there is a clause which states that it may be submitted/captured with LE agencies and other government agencies if it's "reasonably necessary" to meet legal or government-enforceable requests or protect the public. | 500,000 | #12 in Health and Fitness |

| India | Tamil Nadu | COVID-19 Quarantine Monitor Tamil Nadu (Official) | Tamil Nadu Police Department of Health | Quarantine tracker Symptom checker | Only for those in quarantine (on the official database) | No specific privacy policy listed. | 100,000 | N/A |

| India | Aarogya Setu (A Bridge of Health) | Government of India | Contract tracing General information | - Bluetooth - GPS Location | Unavailable at the time of writing but does state that data is shared with the government but your name and number won't be disclosed to the public. | 50,000,000 | #1 in Health and Fitness | |

| India | Corontine | Indian Institute of Technology | Quarantine tracker for asymptomatic carriers | - GPS Location | Not stated. | Beta | Beta | |

| India | COVID19 Feedback | Government of India | General information Test feedback | - Name - Email Address - Mobile # | Not clear. | 100,000 | N/A | |

| India | MyGov Corona Helpdesk - WhatsApp | Government of India | This chatbot helps spread real-time information on coronavirus. When the chatbot gets a message from the user it uses machine learning to reply to the query. | |||||

| Indonesia | West Java | Pikobar App | West Java Provincial Government | General information Latest statistics | - Name - Physical Address - Email Address - Photo - Location - Telephone # - Social Media Address | The app also uses third parties who may collect PII. | 500,000 | N/A |

| Indonesia | West Java | Pikobar Website | West Java Provincial Government | Shows figures of cases and also displays a map which pinpoints where the cases have been reported. When you click on each one it tells you the age of the person, their village, district. | ||||

| Iran | AC19 | Ministry of Health | Location tracking Symptom checker | - Location | Accused of being a way to spy on users. | 4,000,000 | N/A | |

| Ireland | HSE COVID-19 | Health Service Executive | Symptom checker Contact with a healthcare professional | - GPS (recommended) - Symptoms - Age - Medical History - Email Address - Phone # | Data will be stored for 8 years after the remote monitoring finishes. Anonymized or aggregated data may be kept for longer. | 1,000 | #31 in Medical | |

| Israel | VocalisHealth | Defense Ministry's Administration for Development of Weapons and Technological Infrastructure | Symptom checker (using a person's vocal fingerprint) | - Email Address - Phone # | Not listed. | Web-based | Web-based | |

| Israel | Track Virus | Uses Ministry of Health information | Live map of cases Contact tracing | - Location | No user information stored and location history is only stored on the device. However, if the user is identified as having COVID-19, they can submit their location history to the authorities via the settings in the app. | 100,000 | N/A | |

| Israel | Hamagen (The Shield) | Ministry of Health | Contact tracing Location tracker | All data collected remains on the user's phone and nothing is sent back to the Ministry of Health. However, privacy policy does state that "in the future, we shall try to allow diagnosed patients only to send us information on the routes that they have made, in order for to help the MoH and the general public to carry out necessary epidemiological investigations in ever increasing numbers." | 1,000,000 | #2 in Health and Fitness | ||

| Israel | CoronApp | Symptom checker Live map of cases | Any data is shared voluntarily. | Aggregated data may be shared with third parties. Data may also be shared with third parties "to protect the general public." | 100,000 | #98 in Health and Fitness | ||

| Israel | Ministry of Health Website - Map | Ministry of Health offers the public specific location details of those how have been infected with the virus and also a map of those in home isolation. | ||||||

| Italy | Bologna | AutoCert19 Self-Certification | Ministry of the Interior | Certificate for travel | - Name - Address - DOB - Telephone # - Location | Uses Firebase. Personal data is collected and stored for the "time required by the purposes for which they were collected." | 1,000 | #50 in Utilities |

| Italy | Lazio | LazioDrCovid | Salute Lazio | Symptom checker Contact with healthcare professionals (text, audo, or video calls) | Data will be shared with a healthcare professional voluntarily by the user. | 50,000 | #149 in Health and Well-Being | |

| Italy | Sardinia | COVID19 Regione Sardegna | Regione Autonoma Della Sardegna | Quarantine tracker Symptom checker General information | - Mandatory for those entering Sardinia after the start of the emergency | Data is stored for the period in which is required and for 12 months afterward. | 100 | Not ranked |

| Italy | Trento | TreCovid19 | Autonomous Province of Trento | General information Symptom checker | For those submitting their symptoms: - Tax Code - Health Insurance Code - Symptoms (can be requested by healthcare professionals 2/3 times per day) | Uses Firebase. Data shared with healthcare professionals when consented by user. | 1,000 | #199 in Health and Well-Being |

| Italy | Covid-19 | ADiLife Connected Health | Symptom checker Contact with healthcare professionals (video calls) | - Name - Tax Code - DOB - Birth Place - Age - Height and Weight - Age - Email Address - Bluetooth - GPS Location | Data may be shared with third parties and the user must allow Bluetooth, GPS, network, and operational information access in order to use the app. | 10,000 | N/A | |

| Italy | IoRestoaCasa | Federation of Italian Medical-Specific Societies (FISM) | Symptom checker Chatbot function | - Email - Location | Links to general privacy policy. Data will be shared with health authorities. | 5,000 | N/A | |

| Italy | SM-Covid-19 | Health Authorities | Contact tracer | - Bluetooth | No sensitive data required and aggregated data is shared with health authorities. | 5,000 | N/A | |

| Kazakhstan | Smart Astana (Смарт Астана) | Ministry of Health | Quarantine tracker (compulsory) | - Location | Not clear. | 8,000 | #3 in Reference | |

| Lithuania | Vilnius | Karantinas | Municipality of Vilnius | Quarantine tracker General information Symptom checker | - Name - Gender - DOB - Phone # - Profile Photo - Email Address - Isolation Photos - GPS - Bluetooth | All data may be collected, including location data (if shared by the user), and shared with the National Public Health Center. Data isn't mandatory, however. Data is stored for 1.5 years. | 5,000 | #1 in Health and Fitness |

| Malaysia | Sarawak | i-Alerts | Government of Sarawak | General information Live map | -Name - Physical Address - Email Address - DOB (optional) - Gender (optional) | Data can be shared with third-parties, i.e. the government. | 10,000 | #33 in News |

| Mali | SOS Coronavirus | Ministry of Digital Economy and Prospective & Ministry of Health and Social Affairs | General information Submit cases | - Name - Telephone # - GPS Location | Information may be shared with Malian health authorities. | 5,000 | #13 in Health and Fitness | |

| Mexico | Cuernavaca | Covid-19 Cuernavaca | Government of Cuernavaca | General information | - Name - Email or Phone # | Contact details may be used for updates. | N/A | #161 in Notices |

| Mexico | Chihuahua | COVID-19 Chihuahua | Government of Chihuahua | General information | "Users of this page are informed that the Ministry of Public Function has a personal database, which are reserved and are protected with a high level of security, and may only be provided to third parties when as required by a competent authority or specified by law." | N/A | #10 in Notices | |

| Mexico | Jalisco | Jalisco Covid-19 Plan | Secretary of Finance - Government of the State of Jalisco | Location tracker Contact tracer General information Contact with health professionals/authorities | - Name - Physical Location - Telephone # - GPS Location (voluntary) | Users' geolocations is shared with authorities (when they allow this) so they can contact and follow-up the cases of people who are suspected of having or are infected with COVID-19. | 1,000 | #117 in Health and Fitness |

| Mexico | Puebla | COVID Puebla | Government of the state of Puebla | General information Contact with health professionals Symptom checker | - Name - DOB - Telephone # - Address - Gender - Travel History - Geolocation | Due to "reasons of public health" personal data may be transferred to the Ministry of the Interior or the Government Health Ministry Federal in order to help with the security of the population. | 5,000 | #66 in Medicine |

| Mexico | Tamaulipas | COVID-19 Tam | Government of Tamaulipas | Live map Submit cases | - Name - Gender - Age - Phone # - Email Address - Physical Address | Not clear. | 10,000 | #7 in Health and Fitness |

| Netherlands | Amsterdam | OLCG Corona Check | Symptom checker Contact with health professionals | - Name - Email Address - First Four Digits of Zip Code - Region - Phone # - Symptoms - Medical Information - DOB - Age Category | Data is not shared with third parties unless consent given. Anonymized data may be shared with third parties, however. | 50,000 | #3 in Medicine | |

| Netherlands | Medisch Dossier Covid-19 | Medisch Dossier | General information Live map | Not clear. | N/A | #17 in News | ||

| Netherlands | COVID Radar | Leiden University Medical Center (LUMC) | Symptom checker | - Postcode - Symptoms | All data is processed anonymously. | 50,000 | #4 in Medicine | |

| Norway | HelseNorge.no | Norsk Helsenett | Symptom tracker | - DOB - Physical Address | Privacy policy states that it may be appropriate to combine the information with public health registers but in groups, not on an individual level. It also states that the information is stored "indefinitely" but users have the right to request that their information be deleted. | 24,000 | Web-based | |

| Norway | Smittestopp (Infection Stop) | Government of Norway | Contact tracer Location tracker | - Mobile # - Age - GPS - Bluetooth | People who test positive are placed on a registered database. If a user's mobile # is registered, they will receive a text if they have been in contact with someone who has recently tested positive. No personal information is given but it isn't guaranteed that people won't know who the person who has contracted the virus is. | 100,000 | #1 in Lifestyle | |

| Oman | Tarassud | Ministry of Health | General information | Not clear. | 10,000 | #1 in Medical | ||

| Pakistan | COVID-19 Gov PK | Government of Pakistan | Live map General information Chatbot | Unable to view. | 100,000 | #2 in Reference | ||

| Poland | Kwarantanna Domowa (Home Quarantine) | Ministry of Health | Quarantine tracker Location tracker | - Name - Physical Address - Email Address - Telephone # - Selfies - GPS Location | Data is shared with authorities and is deleted 6 years after the app is deactivated (pictures aren't stored for this period). | 100,000 | #2 in Medicine | |

| Portugal | Estamos ON - Covid19 | Government of Portugal | General information | None | Any data collected is done with consent and kept for as long as is necessary for processing. | 10,000 | #17 in Utilities | |

| Portugal | Covidografia | Health Authorities | Live map Symptom tracker | - Facebook Account - Postcode - DOB | All data is aggregated before it is shared with health authorities to help them try and make decisions about the next steps for the pandemic. Privacy policy does state that the company (Tech4Covid19) isn't responsible for how the health authority, DGS, processes the data after it gets to them. | Web-based | Web-based | |

| Portugal | Novo Coronavirus Card (MySNS Wallet) | Ministry of Health | General information | - SNS # - DOB - Mobile # | Data used is only for identification purposes - it isn't stored. Any other information is stored in an encrypted form on the mobile device. | 6,000 | #9 in Health and Fitness | |

| Portugal | CovidAPP | Faculty of Medicine of the University of Porto | Symptom tracker Contact with health professionals | - Mobile # - Email Address - Name - Physical Address - Health Data | All data is aggregated but some contact data may be shared with health professionals if they need to get in touch with the user due to them displaying symptoms. | Web-based | Web-based | |

| Russia | Госуслуги СТОП Коронавирус (STOP Coronavirus) | Government of Russia | Quarantine tracker | - Name - Physical Address - Email Address - DOB - Telephone # - Passport # - Medical ID - Travel History - GPS | When using the app, users are allowing for the data to be collected, processed, and transferred. | 1,000,000 | #1 in Health and Fitness | |

| Russia | Coronavirus - Covid-19 | Verba Klinika | General information Symptom checker | Personally-identifiable information may be collected and may be shared with third parties. | N/A | #39 in Health and Fitness | ||

| Russia | Moscow | социальный мониторинг "Social Monitoring" | Government of Russia | Quarantine tracker Location tracker | - GPS Location | The app did appear on Google Play but has since disappeared. Reviews appeared to show that the app was requesting access to many features of the phone, including files, camera, and fitness trackers. It was also noted that there was a lack of encryption. Data is shared with authorities. | ||

| Russia | Yugra | Телемедицина Югры (Telemedicine Ugra) | Department of Health of the Khanty-Mansi Autonomous Okrug of Ugra | Contact with health professionals Appointment bookings Symptom checker | - Name - SNILS - Phone # - Email Address - OMS/VMI Policy | Data is only shared with third parties if necessary for the service and/or is required according to Russian legislation. | N/A | #138 in Medicine |

| Saudi Arabia | Corona Map | National Health Information Center | Live map Chatbot | No data required or shared. | N/A | #94 in Health and Fitness | ||

| Singapore | TraceTogether | Ministry of Health | Contact tracing Location tracker | - Bluetooth - Mobile # | The app stores records of these encounters and logs will need to be sent to the health ministry upon request. Data on users' phones is encrypted and only stored for 21 days and the app doesn't access any other information, i.e. the user's location. It isn't compulsory to download the app but the government will be encouraging people to. | 500,000 | #1 in Medical | |

| Singapore | covid19SG | Data gathered from Ministry of Health website | Website which displays the outbreaks in Singapore, including the age and sex of those diagnosed. You can also go into each case to find out specific details about the case, including age, sex, and recent travel movements. | Web-based | Web-based | |||

| Singapore | COVID-19 Chat for Biz (Chatbot) | Government of Singapore | General information and help for employers | Web-based | Web-based | |||

| South Korea | 자가격리자 안전보호 (Self-Isolator Safety Protection) | Government of South Korea | Location tracker Quarantine tracker Symptom checker | - Name - DOB - Gender - Nationality - Mobile # - GPS Location - Symptoms - Passport # (Foreign Nationals) | Privacy policy states that people must agree to consent to collection and use of personal information, location information, and sensitive information to use the app. Foreign nationals must also allow unique identification information usage too. All data is stored 2 months after resolution of the virus. | 50,000 | #71 in Lifestyle | |

| South Korea | 자가격리자 전담공무원 (Self-Container) | Government of South Korea | Location tracker Quarantine tracker Symptom checker | - Name - DOB - Gender - Nationality - Mobile # - GPS Location - Symptoms - Passport # (Foreign Nationals) | Privacy policy states that people must agree to consent to collection and use of personal information, location information, and sensitive information to use the app. Foreign nationals must also allow unique identification information usage too. All data is stored 2 months after resolution of the virus. | 10,000 | #195 in Lifestyle | |

| South Korea | Corona 100m (Co100) | Government of South Korea | Contact tracing Location tracker | - GPS Location | Has been criticized as spying on civilians. Not available on Google Play or App Store to check policy. | 1,000,000 | N/A | |

| Spain | ASISTENCIACOVID19 | Government of Spain | Symptom checker | - Name - Mobile # - DNI/INE - Address - DOB - Geolocation - Gender (optional) | Information is to be used to in the interest of public health and as part of the emergency situation so is therefore accessible by health authorities and government agencies. Location data is used to identify which autonomous community the user is in, it is not used for tracking. Data may be stored for up to 2 years. | 10,000 | #53 in Health and Fitness | |

| Spain | Catalonia | StopCovid19Cat | Government of Catalonia | Symptom checker Live map | - Medical ID | Uses Firebase. App also says it will "collect population data in order to be able to create heat maps for the dashboard." Privacy policy not clear on what/how this is done. | 500,000 | #2 in Medicine |

| Spain | Madrid | CoronaMadrid | Government of Madrid | Symptom checker Contact with health professionals | - Name - DOB | The information given by the patient and "Those observed when you use the Application or obtain them from your device (e.g. the operating system of your device, the network from which you connect or your physical location). Remember that you can review and manage the permissions you grant to COVIDAPP to obtain data from your device through the options available on your terminal." Information is shared with relevant authorities, health care providers, law enforcement, and suppliers and partners. No specific names which has raised concerns. | 50,000 | #9 in Medicine |

| Spain | Valencia | GVA Coronavirus | Conselleria de Sanitat Universal i Salut Pública | Appointment bookings General information Contact with health professionals | - SIP number - DOB | Data only used to provide the healthcare services. | 5,000 | #84 in Health and Fitness |

| Thailand | COVID Tracker - Unofficial | Uses information from the Ministry of Health and Facebook | Live map | The "news" includes Facebook posts which describe the movements of an infected person before they were diagnosed. I.e., a student at Mahidol University: https://www.facebook.com/mahidol/photos/a.10153450690529012/10159713714519012/?type=3&theater | ||||

| United Arab Emirates | COVID-19 UAE | Ministry of Health and Prevention | General information | Data may be shared with other government departments. | 50 | #6 in Health and Fitness | ||

| United Arab Emirates | Dubai | COVID19 - DXB Smart App | Dubai Health Authority | General information Live map | - Location | App may use location. Unable to view full policy. | 100 | #51 in Health and Fitness |

| United Arab Emirates | Abu Dhabi | Stay Home | Department of Health - Abu Dhabi | Quarantine tracker Location tracker | - Name - DOB - Physical Address - DOB - Email Address - Telephone # - Camera - Media - GPS Location - Audio - Calls | Data is shared with the department with locations being regularly checked and notifications sent to users. | 5,000 | #94 in Utilities |

| United Arab Emirates | Abu Dhabi | TraceCovid | Department of Health - Abu Dhabi | Contact tracing | - Bluetooth - Mobile # | The App does not require your location to work. Android devices require the location permission to be granted in order for the App to access Bluetooth features. Your location data is not sent to our servers. | 50,000 | #1 in Medical |

| United Kingdom | Northern Ireland | COVID-19 NI | Health & Social Care (HSC) Northern Ireland | General information Symptom checker | - Postcode - Age | No PII is collected but the postcode and age of the user is collected to help track the impact of COVID-19 in NI. | 50,000 | #41 in Medical |

| United Kingdom | COVID Symptom Tracker | King's College London, Guys and St Thomas' Hospitals in partnership with ZOE | Symptom checker (daily) Location tracker | - Name - Phone # - Email Address - Gender - Year of Birth - Health Data - Postcode | Data is shared with the NHS, hospitals, universities, health charities, and other research institutions. It may be exported to international experts. " An anonymous code is used to replace your personal details when we share this with researchers outside the NHS or King's College London. Before sharing any of your data with researchers outside of the UK, we will remove your name, phone number, email address and the last 3 digits of your postcode to protect your privacy." | 500,000 | #1 in Medical | |

| United Kingdom | Scotland | NHS24:Covid-19 | NHS Scotland | General information Symptom checker | Personal data may be collected when filling in forms but will be kept for no longer than necessary. | N/A | #42 in Medical | |

| United States | Georgia | AU Health ExpressCare | Augusta University Medical Center | Symptom checker Contact with a healthcare professional | - PII - Local Practice Details - Email Address - Phone # - Location | Medical records may also be collected from previous healthcare providers. Information may be shared with healthcare providers, insurance companies, other health-related entities, authorized third-parties, research partners, corporate affiliates, and for legal purposes (one of which is to protect the health of the public). | 5,000 | Not ranked |

| United States | Houston, Texas | Houston COVID-19 Testing Site | City of Houston | Submit cases Live map | - Email - Zip Code | The app developers are aggregating the anonymous data to build out the capabilities of the map over the next few weeks. | Web-based | Web-based |

| United States | New York | STOP COVID NYC | Mount Sinai | Symptom checker (via SMS on a daily basis) | - Demographics - Symptoms - Exposure to Virus | The data is designed to help health providers identify clusters of cases so they can ensure the right resources are in the right areas. Data may also be used for long-term research. | Web-based | Web-based |

| United States | COVID-19 Screening Tool (Apple) | CDC, The White House, and the FEMA | General information Symptom checker | No data is shared unless consent is given. Symptom tool doesn't require any personal information or location details on the website, but the app may store details from Apple ID. | N/A | #15 in Health and Fitness | ||

| United States | Unacast Social Distancing Scoreboard | Unacast | States are scored on how well they're carrying out social distancing | "The Social Distancing Scoreboard and other tools being developed for the Covid-19 Toolkit do not identify any individual person, device, or household. However to calculate the actual underlying social indexing score we combine tens of millions of anonymous mobile phones and their interactions with each other each day - and then extrapolate the results to the population level." | Web-based | Web-based | ||

| United States | MTX Disease Monitoring and Control App | Quarantine tracker Location tracker (connected to all incoming flight passengers on NY systems) Symptom checker (daily) | - Mobile # - Symptoms - PII | The data is sent to health officials in real time so they can identify the most at-risk individuals and provide immediate clinical attention to them to prevent the spread to others. It will also monitor individuals who have been in close contact with confirmed cases and physicians and health care officials who have worked work with suspected patients. | ||||

| United States | Carbyne Technology - 911 Data-Led Service | 911 call helper Remote screener (to reduce the risk of first responders being exposed to the virus) | - Camera - GPS Location | |||||

| United States | Opendemic | Harvard University, Massachusetts Institute of Technology | Contact tracing Location tracker | - GPS Location - Health Data - Email Address | Users have to download Telegram. No privacy policy on the Opendemic website -- would it follow the same as Telegram? | |||

| United States | HealthLynked COVID-19 Tracker | HealthLynked Corp. | Live map Symptom checker Submit cases | - Name - Email Address - Physical Address - Phone # | May share your information for the safety of the public etc. | N/A | #20 in Medical | |

| United States | Riverside County | RivCoMobile | County of Riverside | Report violations | - Address of Violation - Type of Violation - Photo (optional) | Personally-identifiable information may be collected and stored. | 1,000 | Not ranked |

| United States | New York | CovidWatcher | Columbia University | Research study Geofencing Surveys | - Zip Code - Location - Age | Only non-identifying data is used and shared. No data is shared with non-research third parties. | N/A | Not ranked |

| United States | North Dakota | Care19 | North Dakota Department of Health | Location tracker (categorized by activity, e.g. grocery shopping) | - Location | Data only stored when someone is in one place for 10 minutes or more. No personal information stored but if someone test positives they're given the opportunity to share their data with the NDDoH. | In development | #48 in Medical |

| United States | Pennsylvania | COVID Voice Detector | Carnegie Mellon University | Symptom checker | No personal data is required to sign up. Emails may only be required for password recovery. | Web-based | Web-based | |

| United States | San Francisco | How We Feel | How We Feel Project with MIT, Harvard, Stanford, and Penn | Symptom checker | - Symptoms | Aggregate data sent to a group of scientists from MIT, Harvard, Stanford, Penn, and other schools. | 50,000 | #35 in Health & Fitness |

| United States | Stanford, California | First Responder COVID-19 Guide | Stanford Medicine (for emergency services in the Bay Area) | General information Symptom checker | - Name - Occupation - County of Work - Symptoms - Age Range - Medical History | Information is not sent to Stanford Medicine but the assessment results are stored on the phone for later review. | N/A | Not ranked |

| Uruguay | Coronavirus UY | Government of Uruguay | Symptom checker Contact with a healthcare professional | - Name - ID # - Address - Telephone # | Personal data is collected and accessed in the government's database and will be accessed by the Ministry of Public Health in order to contact the user. | 100,000 | #4 in Utilities | |

| Vietnam | Hanoi | SmartCity | Government of Hanoi | Quarantine tracker Symptom checker | - GPS Location - Health Data - Email Address | Data is sent to health authorities to ensure people are adhering to their quarantine restrictions and the app is also designed to show how the virus is spreading. | 100,000 | #106 in Productivity |

| Vietnam | NCOVI | Ministry of Health and the Ministry of Information and Communications | Symptom checker General information Live map | - Name - DOB - Address - ID # - Symptoms | Data is contributed voluntarily and is only used by government agencies for the purpose of helping to protect health against the disease. It will also help the Ministry of Health manage the travel information of cases of infection or isolation, promptly detect new cases, and gather comprehensive information about the disease. | 1,000,000 | #1 in Health and Fitness | |

| Vietnam | Covid-19 App | Advanced International Joint Stock Company (AIC Group) and Electronic Health Administration - Ministry of Health, Viet Nam | Contact with health professionals Chatbot General information Live map | Will share information with third parties for a number of reasons, including "personal safety of users or the public." | 100,000 | #1 in Medical | ||

| Vietnam | Health of Vietnam | Ministry of Health | Symptom checker General information | Suspected cases are sent to the health authority. | 500,000 | #11 in News |

These apps and websites collect a range of personal information. Some of it is automatically collected just by interacting with the app. The user’s location, for example, can be pulled from a smartphone GPS or IP address. Other information is volunteered by the user, such as name, address, contact info, and medical info.

Some countries, particularly those where quarantines are strictly enforced, require citizens to download apps. Others are completely voluntary.

Most of these apps have good intentions and could be helpful in the fight against COVID-19, but they could also have long-lasting privacy implications for the people that use them.

In the haste to develop and launch these apps, we found many instances where user privacy and data security was ignored or overlooked. Many fail to adequately secure user data, don’t address how information can be shared with third parties, or lack clear data retention policies.

Here’s the location of all of the government/healthcare apps we have found (to date):

Please note: Any apps that aren’t available on Google Play and/or are website-based apps have been given a score of 500 to create the location point on the map. Please see the table below.

Update: 04/20

We have added over 20 more apps to our list with many countries still being in talks to release even more. Meanwhile, for the apps we had already listed, there have been 43 million more downloads, increasing from 27,839,220 to 71,239,650.

The majority of these (40 million) came from India’s Aarogya Setu (A Bridge of Health) app which went from over 10 million to over 50 million downloads. Interestingly, the app also met with criticisms with many privacy groups saying that the app isn’t healthy for people’s privacy. For example, it’s not clear which ministries, officials, or departments will be accessing the data.

Some apps also dropped through the rankings in the App Store and received few additional downloads. In many cases, this occurred in countries where other apps have been introduced and/or they’re only relevant to specific areas, i.e. a city.

Growth in contact-tracing apps

A number of contact-tracing apps are to be launched in the coming weeks, including an EU-based one, one from the UK’s NHS, and one in Australia. These are thought to be based upon Singapore’s controversial app, TraceTogether.

The Australian Prime Minister, Scott Morrison, hasn’t said that the app will be compulsory but did say, “I will be calling on Australians to do it, frankly, as a matter of national service.”

Apple and Google are also in collaboration to build a similar app. The two tech giants are working to create a technology that would allow smartphones to trace every other device it comes into contact with. Utilizing Bluetooth signals, records would be stored on a user’s phone and alerts sent if and when someone they’ve been in contact with is tested positive.

Although anonymous, none of these technologies can absolutely guarantee that the coronavirus victim’s identity won’t be known. Even though none of their personally-identifiable details will be given, that’s not to say that the person who is alerted to the new case won’t be able to figure out who it is that they have been in contact with.

“Snitching” apps

A number of apps have been developed to allow people to “snitch” on those who aren’t following social-distancing rules.

For example, in the US, an app was launched in Riverside County, California, which allows users to report a violation of the new rules, i.e. unorganized gatherings, the opening of nonessential businesses, and essential businesses who aren’t following health orders, e.g. not wearing appropriate masks or not adhering to social distancing guidelines. Reports can also be accompanied with a photo. So far, over 1,000 people have downloaded the app on Google Play Store.

But in San Francisco, a similar type of feature in the community’s app had to be removed after it received negative complaints from residents who deemed it the “Big Brother” app.

We have also noticed that quite a few countries have online forms available for people to report violations, including one for the Met Police (London, UK) and one in New Zealand (which crashed upon launch as 4,200 people made reports in the first 24 hours). We’ll include more of these in our next update.

Cough/voice detectors

A number of apps are looking to help diagnose (and understand) COVID-19 through a person’s voice or cough. These apps record a cough and use artificial intelligence to deem whether or not they have coronavirus.

Published list of quarantined people

In Chandigarh, India, the government website publishes daily lists of those who are in quarantine and those who have completed a quarantine period. This includes their name, address, age, gender, and quarantine period. The list of those who have completed quarantine also comes with additional notes, i.e. where they have traveled from.

Notable COVID-19 apps

Singapore: TraceTogether

This app works by exchanging Bluetooth signals across short distances between phones to detect if there’s another user within two meters. The app stores records of these encounters and, when requested, these logs must be sent to the Ministry of Health. Any data on users’ phones is encrypted and only stored for 21 days. The app doesn’t access any other information, i.e. the user’s location and it isn’t compulsory to download the app, though the government encourages people to share it.

Other countries known to be utilizing Bluetooth contact-tracing methods are Austria (Stopp Corona app), India (Aarogya Setu app), Italy (Covid-19, ADiLife), and the United Arab Emirates (TraceCovid). Austria and the UAE assure users that data is anonymized and/or data isn’t shared beyond the phone, but India and Italy appear to suggest that data may be shared with governments (even if precise user details and locations aren’t revealed).

China – Aliplay Health Code/Close Contact Detector

Although not compulsory, this app is required in order to move from place to place. A central database collects two types of information – movement and coronavirus diagnosis. A green-orange-red color code indicates free movement, local movement only, and quarantine, respectively. It uses QR codes to see the users’ real-time contact networks, GPS to look at their location, and Bluetooth to sense proximity between phones.

QR codes have to be scanned before someone can enter their workplace, apartment, and other key areas and they also have to write down their ID number, name, recent travel history, and temperature. Telecom operators are also tracking movements, while hotlines have been set up by social channels like Weibo and WeChat so people can report others who are sick. Some cities are also rewarding people for informing them about sick neighbors.

Chinese companies are also implementing facial recognition that can detect citizens who aren’t wearing face masks and can detect high temperatures within a crowd. A number of apps are also using citizens’ personal health information to alert others who are within the same proximity of infected patients or if they’ve been in close contact with someone.

Poland – Kwarantanna Domowa (Home Quarantine)

“People in quarantine have a choice: either receive unexpected visits from the police, or download this app,” Karol Manys, digital ministry spokesman, told AFP.

The app requires people undergoing the mandatory 14-day quarantine (after returning from abroad) to check in with police by registering with facial recognition on the app then submitting selfies throughout the day when the app alerts them. If they fail to respond within 20 minutes, the police are alerted. The app uses geolocation and fines of PLN 5,000 ($1,100) are issued to those breaking their quarantine.

A number of other countries have followed Poland’s quarantine-tracking methods, including Hong Kong, India (in numerous forms in different locations), Italy, Russia, South Korea, the United Arab Emirates, the United States, and Vietnam. In all of these cases, location and user details are being shared with various government agencies and users are often being asked to check-in with the app regularly.

For example, COVID19 Regione Sardegna is mandatory for anyone entering Sardinia, Italy after the state of emergency was declared. In Russia, the “Social Monitoring” app was removed from Google Play after reports that it wanted access to numerous features, i.e. files, camera, and fitness trackers.

Israel – CoronApp

Israel’s app allows people to submit their symptoms and track cases of coronavirus. There has already been a known breach of the data (although the government said nothing had been compromised). A security researcher found the data of 70k+ people was easy to hack using a common tool, and all of the data was stored on a three-year-old server. The bug has since been fixed.

Hong Kong – StayHomeSafe (with Wristbands)

To make sure those in quarantine aren’t leaving their homes, Hong Kong is administering wristbands which are connected to a smartphone app.

A report said that someone who had to wear the wristband was told to walk around the corners of his home so the app would know coordinates of his living space. Those who don’t adhere to these restrictions can be fined 5,000 HKD ($644). At the time of writing, 60,000 wristbands had been made available.

Methodology

To ensure the integrity of the apps/websites included, we have only added those that are available on the Google Play/App Store (as they have rigorous coronavirus app controls in place) and/or have been released by government authorities or trusted healthcare companies. For web-based or general apps, we have focused only on ones that are requesting data or have questionable privacy practices.

Where possible, rankings have been derived from the app’s country of origin. Using a VPN, we altered our location to that of the app’s developers to gain an understanding of the ranking in that country. For example, CoronaMadrid is designed for residents in Madrid, Spain, so we altered our IP address to one in Spain before looking at the app in the App Store to see where it ranked.

Best practices for contact tracing

A Google Doc created by volunteer experts details some of the best practices for developers makingcontact tracing apps. The document now has dozens of collaborators working together to offer guidance on what data is relevant, how it should be collected, and how it should be analyzed for effective contact tracing.

Notably, the authors advise app makers not to collect GPS location data at present due to both privacy and efficacy concerns:

“‘Anonymization’ or ‘de-identification’ of a mobile (eg GPS) location history is difficult to do correctly. Given the weak epidemiological case for this kind of data at present (at least until testing latency is down to hours, not days) we would presently advise apps for most purposes not to try to collect that information for automated contact matching. […] Bluetooth and similar proximity based tracing methods have been identified as the most likely to produce effective warnings to exposed individuals without extremely high false positive rates. However, because they cannot be correlated against any location data, they need to be enabled on a significant fraction of devices before this provides a high likelihood of tracing contacts.”

Although location data can help enforce quarantines, it’s not so useful for actually tracking the spread of COVID-19.

Other surveillance techniques

Telecom data

A number of countries, including Austria, China, Germany, Italy, and the UK, are using telecom data to track people’s movements. The data is being used to see whether social distancing guidelines are being followed and/or to try and find patterns in how the virus is spreading.

Telecom tracking was taken even further in Israel where security service Shin Bet was given the go-ahead to track people’s phone data without requiring a court order. This is in a bid to track the movements of people who have been found to be carrying coronavirus, enabling them to see who they were interacting with in the days and weeks leading up to their diagnosis.

Shin Bet will send the information to the Health Ministry and anyone who has been within two metres of the infected person for more than 10 minutes will receive a message telling them to go into quarantine.

It appears as though phone users won’t have to give their permission in order for Shin Bet to do this. Shin Bet will only be able to use this information to fight the virus and the data will be erased as soon as it has been used. However, there are concerns that Shin Bet isn’t subject to the FOI laws of Israel so their actions could remain a secret. A law would normally need approval by Knesset, Israel’s parliament, but it was thought the approval process would have delayed the rollout, so the Prime Minister passed it under emergency powers.

Immunity certificates

Both the UK and Germany have suggested that they may issue immunity certificates to those who have had the coronavirus and are no longer at risk. This would enable them to return to work/normal life quicker.

Facial recognition technology: China has implemented facial recognition cameras that detect if someone isn’t wearing a face mask (a legal requirement when leaving their homes) and/or if they have a high temperature. In Russia, facial recognition is being used to capture those who disobey quarantine rules in the capital city, Moscow. Despite having 170,000 cameras in place already, the police have requested a further 9,000 to ensure “there is no dark corner or side street left.”

QR codes

As we have already seen, China implemented a QR-code system to track and restrict people’s movements. Russia has followed suit with the same kind of system in Moscow. Each resident has to register online for their unique code which they can show to police if they are stopped when leaving their home for essentials.

Hand stamps with indelible ink

Those arriving in India from abroad or those who are suspected as having coronavirus have their hand stamped with indelible ink. The stamp details when their period of quarantine is due to end. Governments in India are also rumored to be tracking people’s movements on airlines and railways to try and find those who could be infected.

Big Data

The University of Pavia is using anonymized data from Facebook to try and analyze the spread of coronavirus, looking at data on mobility and maps on population density. Meanwhile, Google has created its own COVID-19 Community Mobility Reports which show people’s movement trends over time, looking at different places of interest, i.e. grocery stores, residential properties, workplaces, and parks.

Virtual “electric fences”

In Taiwan, an “electric fence” is created through mobile location tracking to make sure those who should be in quarantine are remaining in their homes. The system monitors phone signals and alerts local officials and police if the quarantined are moving away from their homes or turn their phones off. Officials also call them twice a day to make sure they’re not just leaving their phones at home.

Lists of vulnerable people

In the UK, supermarkets are being given access to a government database that details the 1.5 million people who are classed as “vulnerable shoppers.” This is done in a bid to help supermarkets prioritize delivery slots.

Over the coming weeks, we are expecting a number of new apps that are designed for wide-scale use. This includes the UK’s NHS app which is currently in development with NHSX. It will use an algorithm to identify patients who are most at risk of having complications if they contract the virus and this will be recorded in numerous places, i.e. electronic records and GP systems. Approved organizations will also have access to this data to help them fight the pandemic.

The WHO is also due to release its own app which will provide up-to-date information and asks users to disclose their location so they can perform contact tracing.

Elsewhere, a GSMA global tracking system may be in production. The mobile phone industry has explored the creation of a global data-sharing system that could track individuals around the world. As of the end of March, these talks were in their early stages and decisions haven’t been made yet about whether or not this will move forward.

We will undoubtedly see a large number of other apps being released on a daily basis and will be updating our findings as we go along.

COVID-19 app survey: How do people feel about their privacy amid the pandemic?

To find out how the general population feel about their privacy when it comes to combatting the virus, we commissioned a survey of 1,500 people in the US and UK (3,000 in total) to find out whether people are more willing to compromise on privacy in order to use such apps.

78% of survey respondents said they would be willing to sacrifice any or some of their usual privacy principles in order to help fight and prevent the spread of COVID-19.

The survey was conducted by OnePoll, a UK-based market research firm.

Here are a few key stats from the survey:

- 78% of respondents would forego any or some of their usual privacy principles (e.g. sharing personal data with the government and other relevant third parties) in order to help fight and prevent the spread of COVID-19.

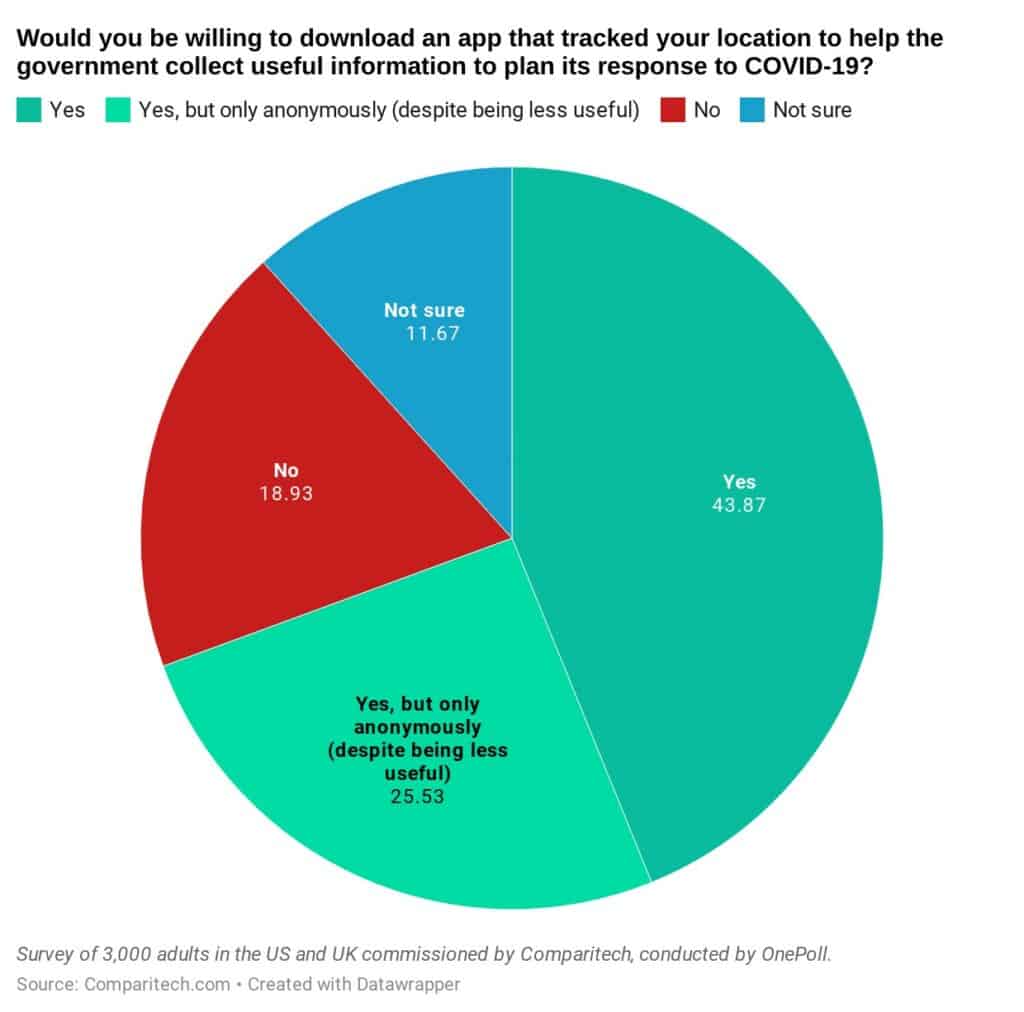

- 44% would be willing to download an app that tracked their location to help the government collect useful information to plan its response to COVID-19. A further 26% would do so if the app was anonymous, despite it being less useful.

- 94% would be willing to provide their name, age, and gender to a COVID-19 tracking app if they exhibited symptoms.

- 62% would be willing to tell an app all of the places they’ve visited recently to alert others who might have been who might have been in the area. A further 25% would do so anonymously despite it being less useful.

- 58% would be willing to provide frequent location updates to a government app to confirm they’re sticking to quarantine restrictions. A further 24% would do so anonymously despite it being less useful.

The survey results revealed some other interesting trends when broken down by region, age range, and gender.

- Men were more willing than women to download contract tracing apps, forego their usual privacy principles, and provide the government with location updates

- Younger people were more likely to opt for anonymous apps and data collection than older people, despite anonymous data being less useful

- 25- to 34-year-olds were the most willing to forego their usual privacy principles to help combat COVID-19

People living in the Northeast and West regions of the US were, broadly speaking, more likely than the rest of the country to provide apps with identifying personal and location data. Those include hard-hit states with densely-populated cities like California and New York.

Similar variations were observed in the United Kingdom. Respondents in Northern Ireland, in particular, were significantly more likely to give apps personal information and compromise on privacy.

Sources

For a full list of the apps and links, please see this sheet here: https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1JYLJiqBYoXQEie-baa-a8z1CV_UNrYc6Fi8mxhnJoDA/edit?usp=sharing