The Consumer Privacy Bill of Rights is not a single piece of legislation, but rather a term used to describe several legislative attempts to regulate the processing of electronic personal data in the US. Also called a “Privacy Bill of Rights,” or, more broadly, an “Internet Bill of Rights,” these proposed measures would enshrine consumer privacy a basic American right, but so far none have become law.

All of the proposed legislation heralded as a Privacy Bill of Rights seeks to accomplish similar goals. It aims to regulate businesses that collect personal data from users in order to provide consumers more individual control, privacy, and security when it comes to their data. Common themes include:

- Security – Businesses are required to responsibly secure and handle personal data

- Transparency – Consumers have a right to know what personal data a company has on them, as well as the right to correct that data when inaccurate

- Access control – Businesses are limited in how and with whom personal data can be shared with third parties.

- Consent – Companies must get opt-in consent from users before collecting, using, or sharing personal data

- Accountability – Government enforcement of the above measures.

The different proposed measures vary slightly in what they seek to accomplish, but that’s the gist of it.

The evolution of the Privacy Bill of Rights

To get the whole picture of how the Consumer Privacy Bill of Rights evolved over time, here’s a brief timeline:

- 2009 – The FTC hosts a series of roundtable discussions to determine how best to protect consumer privacy in areas like social networking, cloud computing, advertising, mobile marketing, and the collection and use of personal data by retailers, data brokers, and other businesses.

- 2010 – The US Department of Commerce publishes a report on commercial data privacy proposing Fair Information Practice Principles (FIPPs), breach notification rules, and a Dynamic Privacy Framework.

- 2012 – The Obama administration introduces a blueprint for the first “Privacy Bill of Rights,” a voluntary code of conduct focusing on transparency, respect for context, security, access and accuracy, focused collection, and accountability. The blueprint didn’t get much attention.

- 2015 – Obama unveils a draft bill of the Consumer Privacy Bill of Rights Act of 2015. The proposal received sharp criticism both from privacy advocates, who claimed the bill contained too many loopholes, and tech companies, who argued the bill would have imposed burdensome regulations.

- 2017 – In its last week in office, the Obama administration publishes a report on the White House website that recounts previous attempts at privacy legislation, and gives advice on the subject to the incoming administration. The subsequent Trump administration promptly removed the report once in office.

- 2018 – In January, telecom titan AT&T advocates for an “Internet Bill of Rights,” calling on Congress to make new laws “that govern the internet and protect consumers.” Pro-net neutrality critics immediately blasted AT&T, calling the company hypocritical due to its many previous efforts to stymie net neutrality and broadband privacy.

- 2018 – In April, Senate Democrats introduce the CONSENT Act, which they call a “privacy bill of rights.”

- 2018 – In October, Ro Khanna (D-California) introduces a new “Internet Bill of Rights,” which includes many of the same measures as previous privacy legislation, combined with some net neutrality protections.

Internet companies and device-makers were generally against Obama’s 2012 proposal and 2015 bill. Today, however, data privacy is a much larger topic in our everyday discourse. More of our data is being collected, while data breaches and incidents of abuse, such as election hacking, are becoming more frequent. For these reasons, tech companies seem to be more willing to accept regulation, albeit reluctantly.

The remainder of this article will focus on the three main proposals for a Consumer Privacy Bill of Rights put forth by politicians: the Obama administration’s original bill, the CONSENT Act, and Ro Khanna’s Internet Privacy Bill of Rights.

Consumer Privacy Bill of Rights Act of 2015

After few took interest in the Obama administration’s 2012 blueprint, the White House drew up its own draft bill in 2015: the Consumer Privacy Bill of Rights Act of 2015. It was intended to set conditions of the lawful processing of personal data, similar to Europe’s GDPR. The bill provided a baseline of protections for consumers, including the stipulations that organizations must:

After few took interest in the Obama administration’s 2012 blueprint, the White House drew up its own draft bill in 2015: the Consumer Privacy Bill of Rights Act of 2015. It was intended to set conditions of the lawful processing of personal data, similar to Europe’s GDPR. The bill provided a baseline of protections for consumers, including the stipulations that organizations must:

- Process personal data in a manner consistent with the context in which consumers provided the data.

- Allow consumers to opt out if their personal data is used unreasonably for the context.

- Delete and de-identify personal data in a reasonable amount of time

- Implement reasonable security for personal data.

- Develop a code of conduct for handling personal data (in some industries).

CPBORA received sharp criticism both from tech companies and privacy advocates. Tech companies gave the usual boilerplate reasons for opposing regulation–undue burdens, stifling innovation, less competition, etc. Needless to say, it never passed.

Privacy groups argued the bill would allow tech companies to write their own rules, rather than giving the FTC the power to set and enforce regulations. They also pointed out that the national law would undermine state laws that offer stronger protections. Even the FTC itself showed concern that the bill did not give consumers enforceable safeguards.

The CONSENT Act

The Customer Online Notification for Stopping Edge-provider Network Transgressions Act (PDF) was proposed in the wake of the Facebook-Cambridge Analytica scandal, in which millions of Facebook users unknowingly had their account data used for targeting in political campaigns.

The Customer Online Notification for Stopping Edge-provider Network Transgressions Act (PDF) was proposed in the wake of the Facebook-Cambridge Analytica scandal, in which millions of Facebook users unknowingly had their account data used for targeting in political campaigns.

The bill would require the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) to establish online privacy protections and reign in data-hungry companies like Facebook and Google. It seeks to accomplish a few things, including companies having to:

- Obtain opt-in consent from users before sharing, selling, or using personal information

- Develop reasonable security practices

- Notify users in the event of a data breach

- Notify users about all collection, use, and sharing of personal data

Some critics have raised concern that the definition of personal information is not broad enough, such as not including email addresses or names among the information that requires consent.

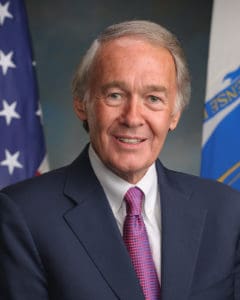

The CONSENT Act has been introduced in the Senate and is in committee at the time of writing. Ed Markey (D-Massachusetts), who introduced the bill, has received campaign contributions from telecoms including Comcast and DISH Network.

Ro Khanna’s Internet Bill of Rights

Ro Khanna’s Internet Bill of Rights is not yet an actual bill, and it was instead introduced as an op-ed in the New York Times. He put forth a list of principles that we can expect to surface in an actual draft bill later on. It invokes many of the same themes as previous privacy bills plus a few net neutrality protections. Some key points include:

Ro Khanna’s Internet Bill of Rights is not yet an actual bill, and it was instead introduced as an op-ed in the New York Times. He put forth a list of principles that we can expect to surface in an actual draft bill later on. It invokes many of the same themes as previous privacy bills plus a few net neutrality protections. Some key points include:

- Consumers have knowledge of and access to all personal information held by companies.

- Companies must gain opt-in consent to collect or share personal data.

- Consumers must be able to obtain, correct, or delete personal data held by companies “where context appropriate.”

- Businesses must notify users in a timely manner in the event of a data breach.

- In accordance with net neutrality, ISPs may not block, throttle, or engage in paid prioritization of the internet in ways that unfairly favor specific content, applications, services, or devices.

- With respect to broadband privacy, ISPs may not collect personal data that is unnecessary for them to provide internet without opt-in consent.

- Consumers have the right to universal web access, and there should be clear and transparent pricing for internet services and providers.

- Consumers have the right to data portability and can move their data from one network to another.

- Businesses must have reasonable security practices in place to protect personal data.

- Consumers have a right to be informed if there is a change of control over their data.

- Consumers enjoy freedom from warrantless metadata collection, including government surveillance.

- There are no more gag orders; companies have the right to disclose details about government data requests to the public.

The goal of Khanna’s plan seems to be to expand California’s new Consumer Privacy Act to the rest of the US. That law, which passed earlier in 2018, empowers consumers with the right to know what information any company has collected about them and with whom that information is shared. Consumers can demand a company delete their personal data, and companies must provide equal service to customers no matter what information they’ve collected.

Khanna’s proposal is more broad than previous attempts at legislation. It takes aim at internet service providers (ISPs) in addition to internet giants, and it adds net neutrality to the fray. Although net neutrality is certainly a hot topic in the tech industry, it’s not specifically related to privacy, which is perhaps why Khanna calls it an “Internet Bill of Rights” instead of a “Privacy Bill of Rights.” It’s unclear if it will all be put forth under a single bill or split into multiple pieces of legislation. It’s also not clear what government entity will be responsible for enforcement.

As a Democrat, Khanna’s attempts at privacy legislation are unlikely to pass in the current Senate, which remains under Republican control. Furthermore, his California constituency includes Apple, Google, and Facebook—huge tax revenue drivers for the state that also happen to be among the worst perpetrators of the very sorts of bad privacy practices he’s trying to prevent. Khanna has received campaign donations from Alphabet (a.k.a. Google) and many other tech companies in the past, so we should approach any forthcoming legislation with skepticism.

If passed, a Privacy Bill of Rights could fundamentally alter the advertising-based business models that so many internet companies rely on, from giants like Google and Facebook to small publishers and blogs. The specific language of the law and actual implementation will ultimately govern the outcome. For example, how easy do tech companies have to make it for the average person to view, modify, move, or delete their personal information? Convenience for end users will play a huge role in whether such a law would actually have an impact.