We are perpetually being watched online by virtually everyone—government, hackers, advertising agencies, ISPs and big tech companies. They harvest all sorts of data about us from our devices and online activities, often without our consent. It’s so stealthily done that you rarely get to experience the creepy feeling of being watched. Because we don’t get to see how this plays out in reality, we often fail to appreciate the enormity of the risk.

Imagine being in your home and suddenly realizing that over ten people are peeping into your windows and continuously prying on your private activities. How would you feel if you suddenly realize that you are being followed around by over ten salespersons in a store? —It’s that serious.

Even our smartphones, which have become an indispensable part of our lives, and the apps that run on them are not spared. We use them to carry out day-to-day tasks from interacting with friends via calls and social media apps to keeping track of our finances and health status.

As more and more people use smartphones to access the internet, privacy concerns continue to grow. Users are worried that the apps installed on their smartphones may be snooping on their activities, gathering their personal data, and sharing them with third parties or sold for profit. This is what Harvard University scholar Shoshana Zuboff calls surveillance capitalism.

Surveillance Capitalism

Surveillance capitalism is the monetization of personal data captured through spying on user’s online activities and behaviors. It is the prevailing business model of the internet.

Under surveillance capitalism, we’ve lost control of our devices and data. If you are not careful enough, most of what you do online and in mobile apps will be aggregated and used to build up a detailed digital profile of you, and eventually sold to advertisers for commercial gain. But increasingly, even careful users find it hard to escape being caught in this digital marketing dragnet.

Location tracking, for example, is used by cellular phone networks and tech companies to deliver calls and other location-based services to subscribers. In order to make and receive calls, your service provider needs to know where you are at all times. As you move around with your phone, you are indirectly saying to your service provider, “I allow you to know where I am at all times, in exchange for the ability to make and receive calls”.

This isn’t stated in any contract; it is inherent in how the service works. Your cell phone tracks your location at every point in time—where you live, where you work, where you like to spend your weekends, etc. The accumulated data can be used to build a digital profile of you and how you spend your time. There is another entirely different and more accurate location system built into your smartphone. It is called the Global Positioning System or GPS. This is what provides location data to the various apps running on your phone. Tech companies such as Google, Facebook, Uber, Lyft, Airbnb, Tinder, and Pokémon Go use it to deliver location-based services. If you depend on all of those services, you’ll find it difficult to escape location tracking.

Surveillance capitalism is more prevalent in the Android operating system. In fact, Android’s ecosystem of free apps that run on your smartphone feed on your personal data. Many were designed and orchestrated primarily to collect data about you and use it to deliver targeted ads. Most users are not comfortable with this kind of arrangement, and this has led to increased privacy concerns. In this piece, we provide possible ways you can use to tell if an app is sharing data about you with third parties, what data is being shared, and what you can possibly do to protect your privacy.

See also: How to secure your Android apps permissions

Free Mobile Apps

If you use free apps on your device, chances are you are already being tracked. Your personal data may have been commodified for in-app advertising and data monetization.

App developers invest lots of time and effort into developing and maintaining apps. Yet despite all of that, we use the vast majority of them for free.

So how do they make money you may ask?

The answer is simple: in-app advertising and data monetization. To display ads inside an app, you need to garner data about your users, as well as the businesses interested in selling services to different user demographics. This can be difficult to manage for most app developers. To lessen this burden, developers make use of third-party intermediaries to facilitate mobile advertising services by embedding codes that allow them to collect data about users and use it to display targeted advertisements.

Developers are not obligated by app stores to disclose their use of third-party advertising and tracking services, and so users are largely unaware of what’s going on. Even apps that are truly ad-free track users for other purposes such as analytics and crash reporting, and there are also third-party services that facilitate those functions behind the scenes.

To avoid this kind of scenario, it is best to minimize your use of free apps and where possible take advantage of premium alternatives. The reality is if you are not paying for a product, then you are most likely the product, not the customer.

Excessive App Permissions

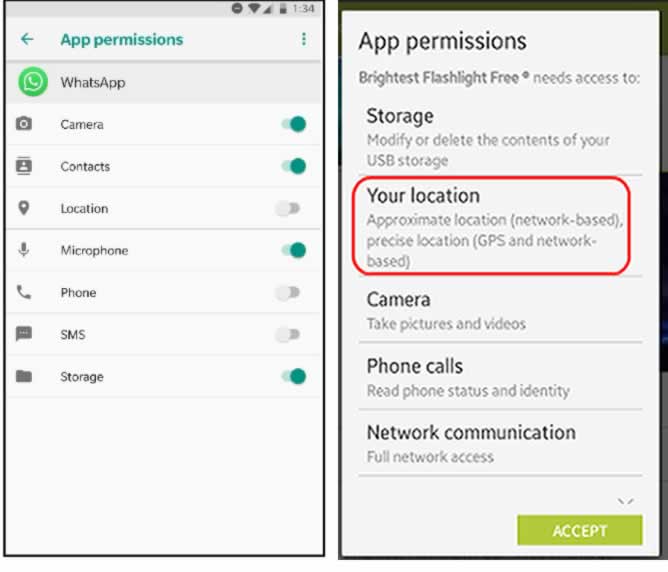

App permissions serve as virtual barriers between the app and specific parts of your phone’s data. When you install a new Android or iOS app, it asks for permission before accessing personal data, and the onus is on the user to decide whether to open the door or not. The app platforms even encourage developers to explain to users why the app wants certain permissions. Generally speaking, this is positive, and some of the data collected are necessary for them to function properly. A flashlight app, for example, cannot function without access to the camera flash.

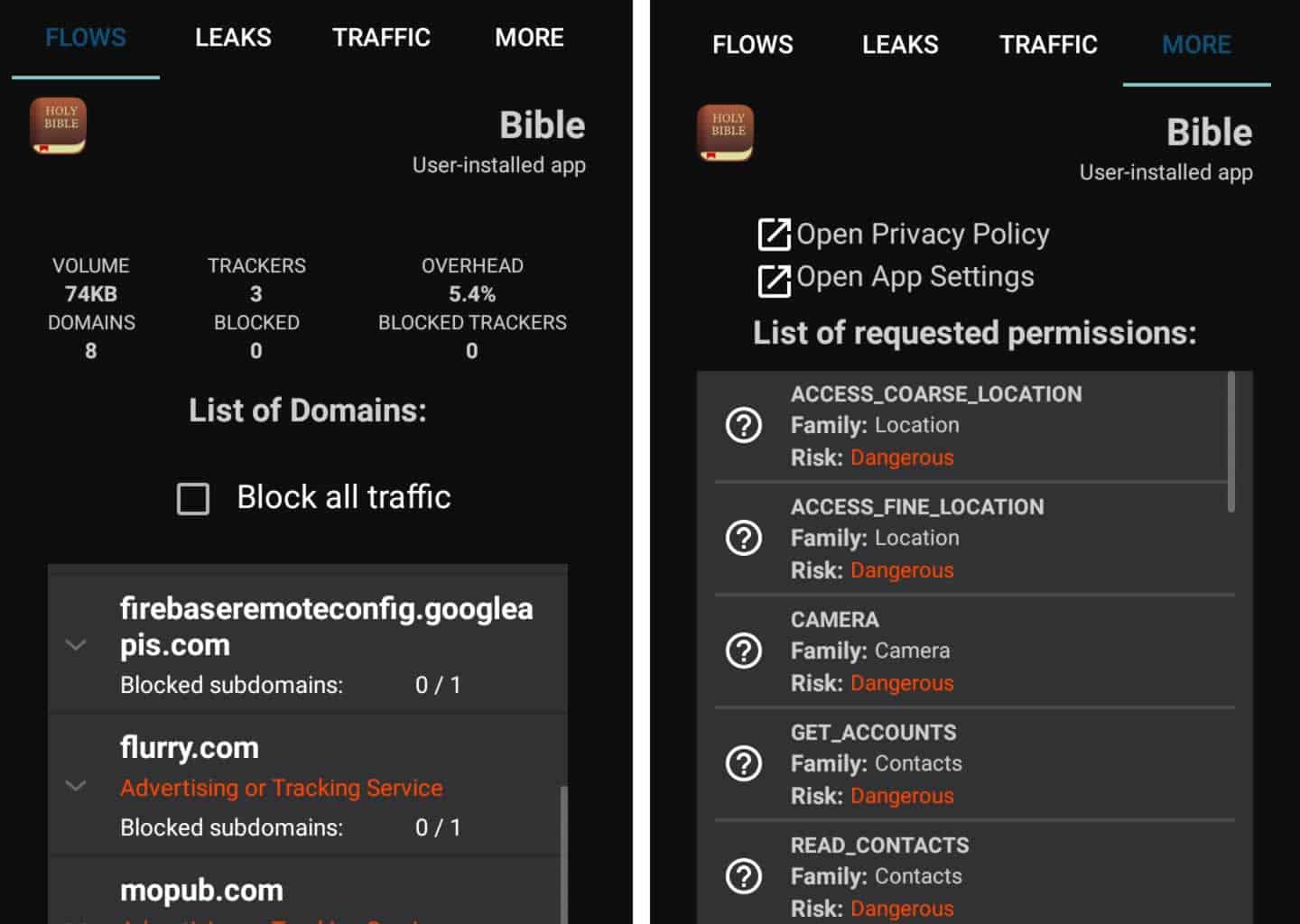

But once an app has permission to collect that data, it can potentially share it with anyone—allowing third party entities to keep track of your activities. Therefore, any permission that is not required to the function of the application should be considered excessive, and should instantly give you the hint that something more sinister may be going on. A flashlight app needs access to the flash and nothing else. A Bible-reading app does not need access to the camera.

It is also important to regularly audit app settings and where possible revoke access to something you previously gave permission to if you no longer use those features. This helps to scale down the volume of data collected about you. It is your responsibility as a user to make sense of privacy permissions and to apply the right judgment when granting apps access to your microphone, camera, contacts, locations, and other critical data points. The safest way to keep an app you don’t trust from tracking you is to completely uninstall it or to not download it at all in the first place.

Advertising IDs

Both Android and iOS require apps to use a special ID called advertising ID for tracking smartphones. This special ad ID is linked to your personal data. Mobile advertising IDs allow mobile app developers to identify who is using their mobile apps. It can be sent to advertisers and other third parties which could be used to track the user’s activities and behaviors.

As consumer time spent on mobile continues to grow, the personalization of advertising and content becomes more and more attractive to marketers. By accurately identifying individual users and establishing profiles of their behaviors, advertisers can create and manage consistent models of user identity needed to follow them around across devices and apps both online and offline.

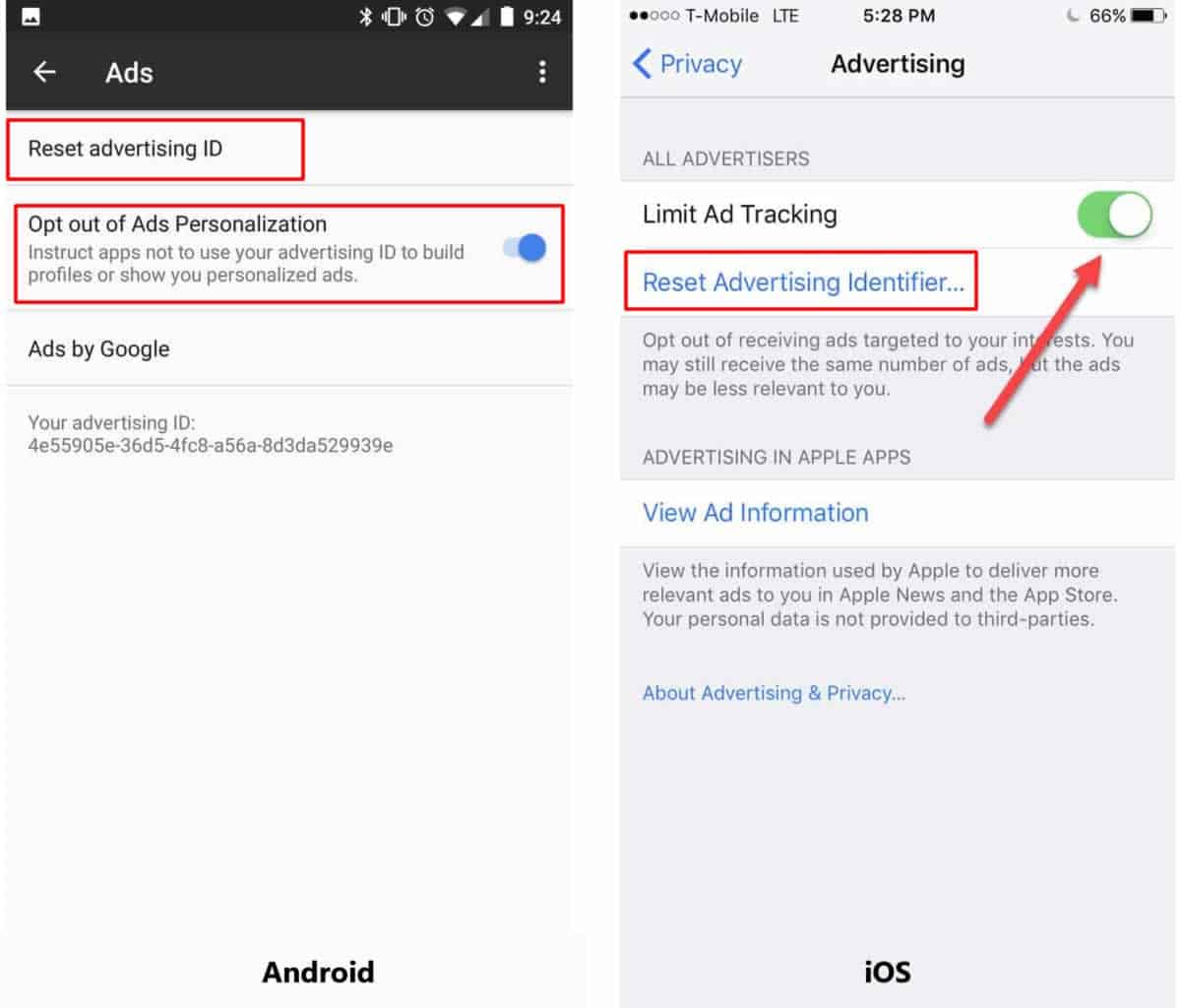

But the good thing about having a designated ad ID is that both Android and iOS allow you to reset your ID or even opt-out of ad personalization. Resetting your ID disrupts the digital profiles advertisers have already built about you, and keep them from growing even more. By opting out, you prevent advertisers from tracking your activities through your ID. The steps for resetting your ad ID and opting out of ad personalization are basically the same for all versions of Android, although there may be some slight variations.

To reset on Android, go to Settings > Google > Ads > Reset advertising ID and click OK when the confirmation screen appears. To opt-out of ads personalization toggle on the Opt-out button.

On iOS, navigate to Settings > Privacy > Reset Advertising Identifier and then Reset Identifier when the prompt comes up. To opt-out of ads personalization toggle on Limit Ad Tracking button. Please see the screenshot below for Android and iOS.

Privacy Policies

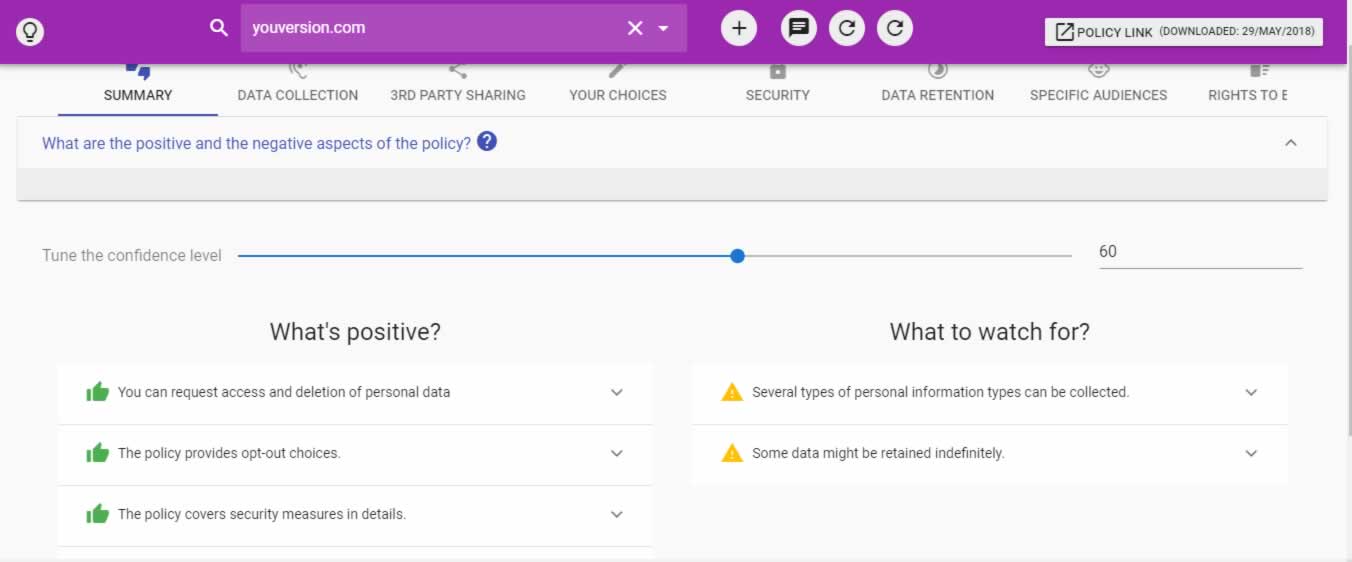

It’s hard to tell what personal information is collected about a user, how it is used and with whom it is shared. After all, business transactions of this nature only happen in private. The privacy policy document is set out to address those concerns. Users are therefore encouraged to read policy documents in order to know if an app is sharing data about them with third parties, and what data is being shared.

But in reality, when you download and install a new app, you probably don’t bother to read its privacy policy before rushing to agree to the terms of service. Even people who do read privacy policies struggle to understand them because they are usually buried in long legal documents perfectly crafted to make it uninteresting to a regular user.

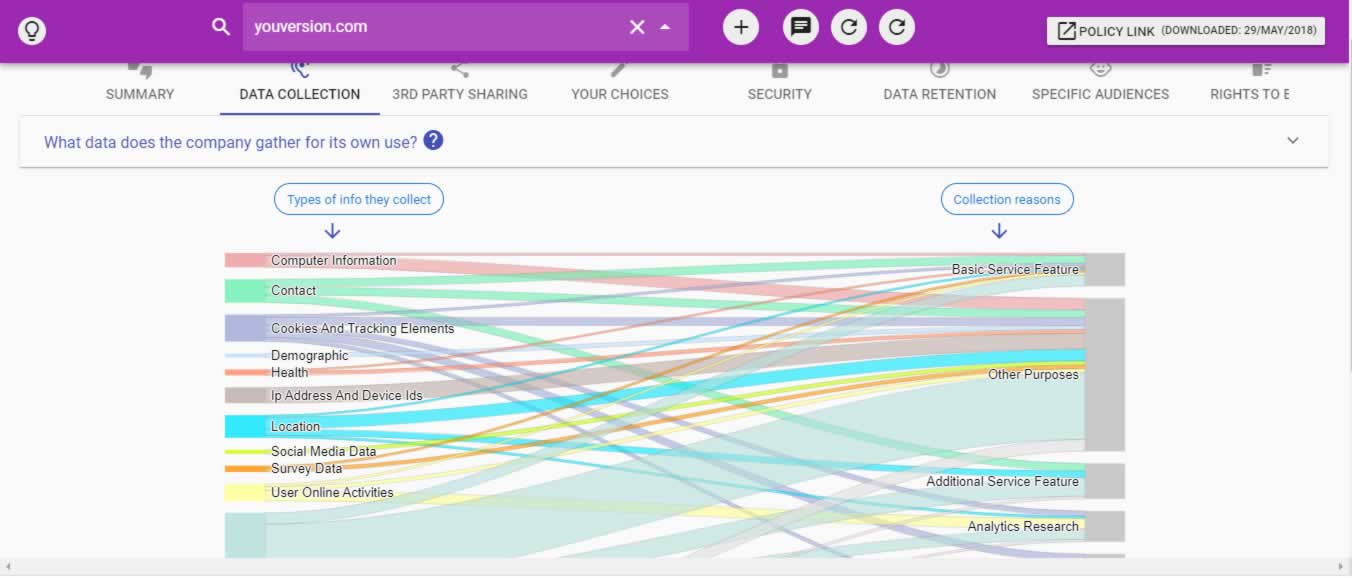

Nonetheless, the good news is that there are AI tools out there such as Guard and Polisis that can read and analyze the privacy policies of various apps for us, providing a summary of the positive and the negative aspects of each policy, including data collected and third party sharing details if any. Please see screenshots below showing summary and data collection details for YouVersion Bible app on Polisis AI tool. Take advantage of those tools and get to understand how and with whom your personal data is being shared.

Traffic Analysis Tool

Lastly, another technique you can use to determine if an app is sharing data about you with third parties is a traffic analysis tool. A typical example of a traffic analysis tool is the Lumen Privacy Monitor. It is a free Android app that analyzes the traffic apps send out, and reports which apps actively harvest personal data.

Note that Lumen is also a research tool created for academic research purposes. So you’ll be asked to allow it to collect some data about what Lumen observes apps are doing on your phone—but according to the creators that doesn’t include any personal or privacy-sensitive data.

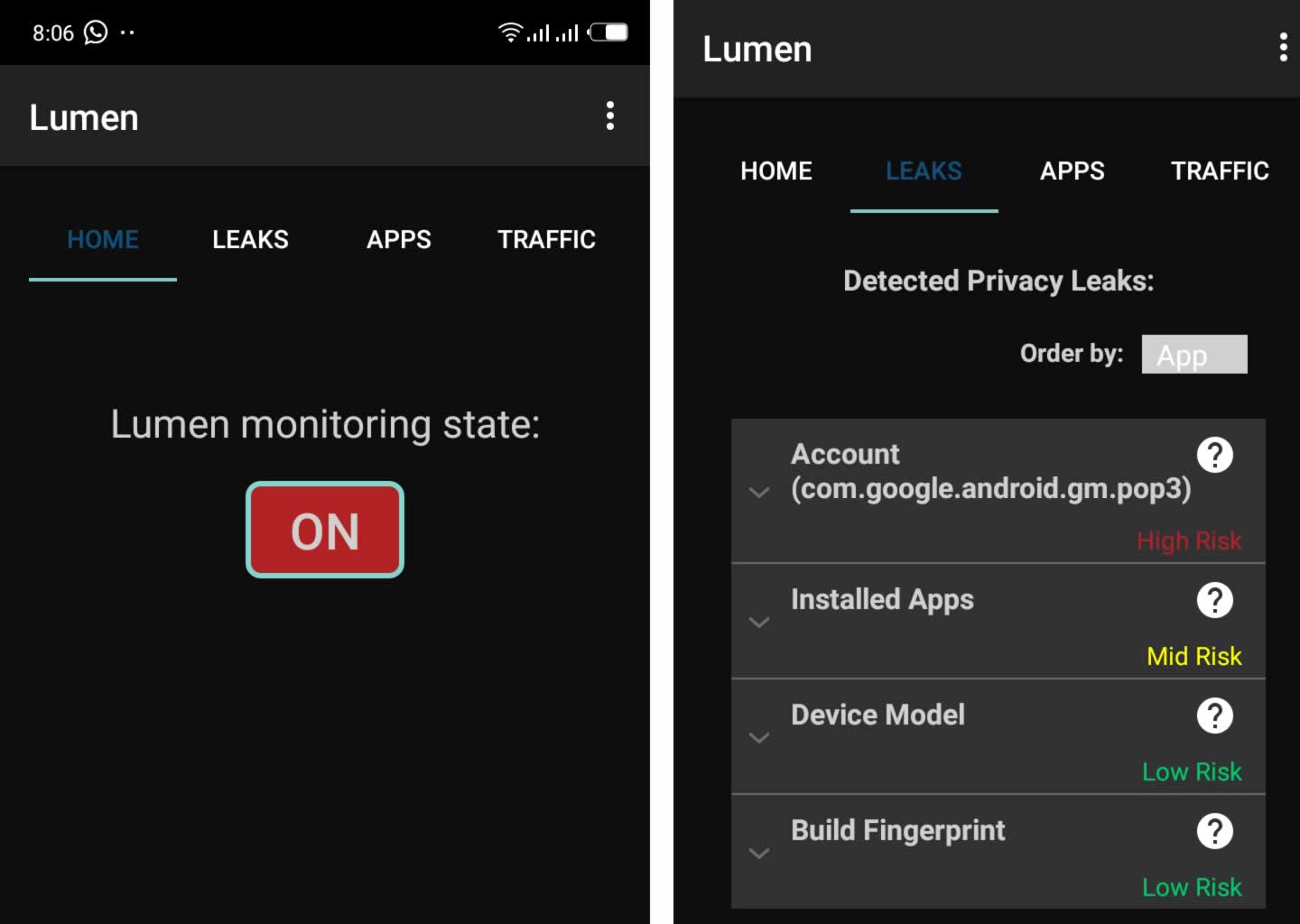

Once you download and install it on your phone, change the state from OFF to ON as shown on the screenshot below, to switch on the app. This will enable you to see the data installed apps collect in real-time, whether they are sending that data out to third parties, what internet sites they send the data to, the network protocol they use and what types of personal information each app sends to each site. There are three tabs on the main interface: LEAKS, APPS and TRAFFIC.

- LEAKS display detected privacy leaks (personal or device-related) and the associated risk level.

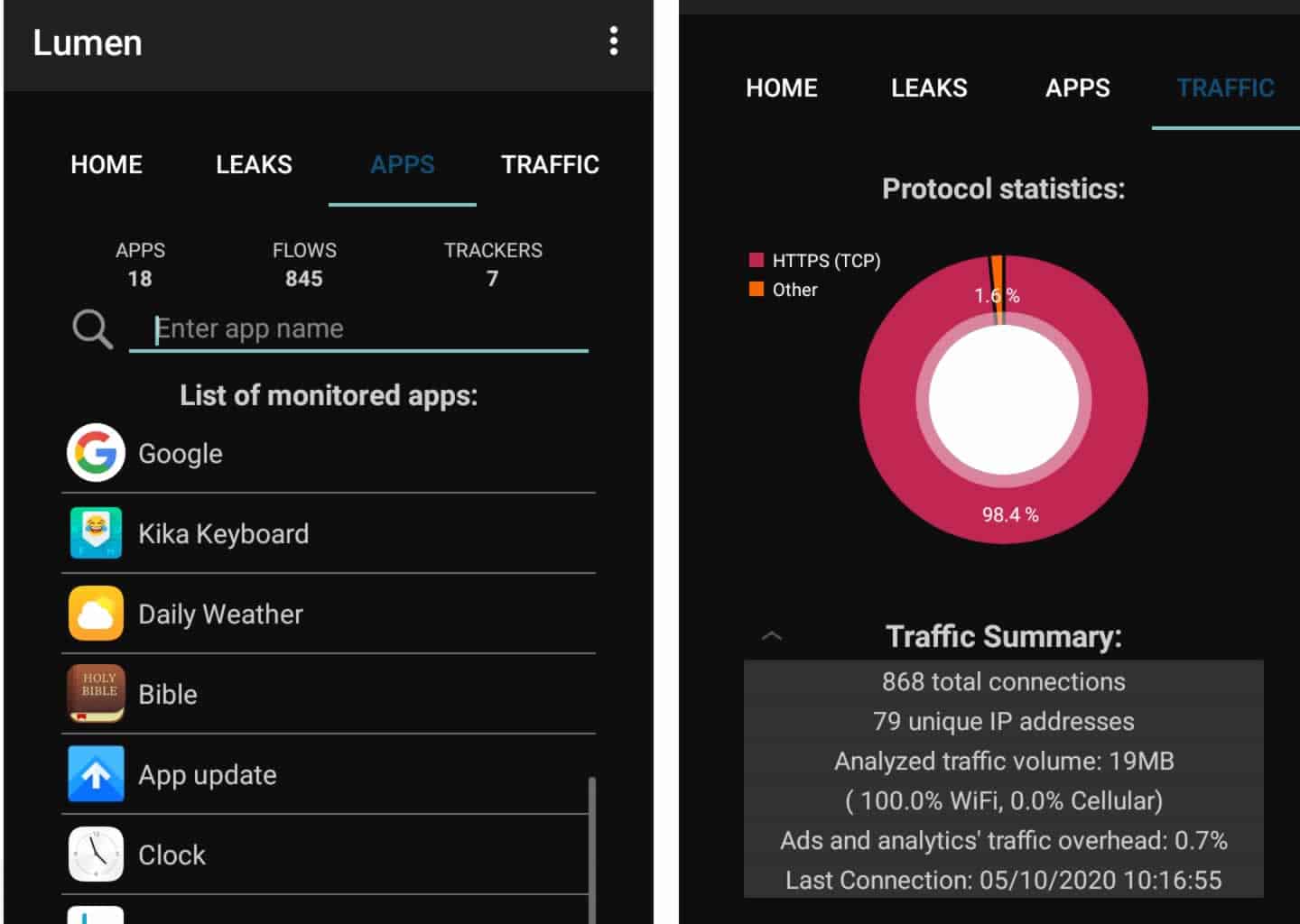

- APPS display lists monitored applications that Lumen picked up, with options to display a detailed report about individual apps.

- TRAFFIC presents a graphical summary of protocol statistics; including information about analyzed traffic such as HTTPS/HTTP/DNS and other traffic, bandwidth, and the overhead that ads and analytics scripts cause.

The APPS tab is perhaps the most interesting as it reveals vital information about the behavior of installed apps on your phone. A tap on a monitored app displays interesting information such as the list of domains the app attempted to establish connections to (with the option to block them), the number of trackers and the overhead caused by them, leaks and traffic-related information associated with the monitored app, and the list of requested permissions and the associated risk level. From the list of apps displayed on the APPS screen as shown on the screenshot above, we tapped on the Bible app and observed the following as shown on the screenshot below:

With the information provided, you would be better equipped to make informed decisions. For example, the information about the list of domains can help you determine whether they are necessary or not; and while you may need to research them further to understand why the application may want to establish such connections, you’d quickly discover unwanted connections to third party tracking servers. The list of requested permissions and its associated risk level will help you decide whether to keep an application installed, to completely uninstall it, or block some features.

But blocking some features may impair app performance or user experience. It may cause the app to malfunction if it cannot load ads. Blocking ads actually denies app developers a source of revenue to support their work on apps, which are usually free to users.

Perhaps, if people were more willing to pay developers for apps, they would probably not indulge themselves in the practice of in-app advertising and data monetization, though it’s not a complete solution. Ultimately, trust and a strong regulatory framework may hold the key to ending this menace.

See also: How to protect your privacy on Smartphones and Tablets