You’ve probably heard about cookies and know that they are involved in tracking you across the internet. However, most people tend to get fuzzy when it comes to the details of how they work, and how they can avoid being tracked by them.

You may have even heard that third-party cookies are slowly being phased out. But what does this really mean, and how will it affect your privacy in the future? Cookies and the rest of the online landscape can be complicated, but don’t worry, because we’ve created this full rundown to explain:

- What cookies are.

- The different types of cookies.

- How the changes to third-party cookies will affect you.

- How you can stay safe in the future.

Despite their reputation as spies on the internet, cookies aren’t always bad. They can help to keep you securely logged into a website as you navigate across its pages. Without them, you might have to reenter your username and password every time you try to go to a new page.

Cookies can also help to remember your preferences, such as your favorite settings on a website, or how you like a certain page to look. Then there’s the sinister, yet widely known use: tracking you across websites, often so that some organization can make money from advertising.

At their core, cookies are just packets of data that are passed between computer programs. The data tends not to be particularly meaningful for the recipient program, but gives the other program significant information when they interact in the future.

A good way to think of them is like a ticket for valet parking. When a person hands over their car keys to a valet, they are given a ticket or token in return. Often this will have some information on it that is completely meaningless to them, such as a company-only code for a parking spot, like D46. The person might have no idea where D46 is, but it doesn’t matter.

When the person returns to the valet, they hand over their ticket. The valet sees that it says D46 and knows the precise parking spot. The valet goes to the parking space, picks up the car, then drives it back to the customer. Even though D46 was completely meaningless to the customer, the information on the ticket gave the valet the details they needed to know in order to return the car.

Cookies are very similar. Your web browser may not really know what a particular cookie indicates when a website sends one to you, just like the customer didn’t know where D46 was. But when you interact with the website in the future, the site can see the information stored in the cookie, which it then uses to facilitate the transaction, remember your settings, or track you.

You will be most familiar with the cookies your browser receives when interacting with websites. To be technical, these are called HTTP cookies, but no one really talks about the other types anymore, so this article will simply refer to them as cookies throughout.

Cookies were born in the mid-nineties, when Netscape employee Lou Montulli floated the idea as a solution for building a shopping cart for a website. Back then, we didn’t have the infrastructure for ecommerce that we do now, and one of Netscape’s client’s, MCI, wanted to be able to keep track of ongoing transactions without storing the data on its own servers. Instead, it wanted the relevant information to be stored on the customer’s computer.

Montulli came up with a session identifier that had a memory mechanism, but wouldn’t allow cross-site tracking. Essentially, the web server would send information to the browser, which the browser would then store. This information—the cookie—could include things like a session identifier, username, shopping cart items, and much more.

This made it possible for sites to complete the shopping process without the website having to keep track of the user at every step of the way. Instead, the website would receive the necessary information from the cookie when the browser interacted with the server.

A cookie specification was developed for Netscape in 1994. Internet Explorer began supporting cookies in 1995. While Montulli applied for a patent in 1995, it wasn’t granted until 1998. The first Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF) specification was completed in 1997, with a handful of updates released over the following decades.

Cookie exchange occurred silently, under the hood, without any obvious alerts to the user. This kept them from being widely known about, at least for the first year or two. It wasn’t until 1996 that they started attracting controversy. The Financial Times published an article comparing the mechanisms behind them to a camera following a person around the grocery store, recording not just every purchase, but even the items the person considered.

While this type of tracking may seem banal in our current surveillance state, many were alarmed by the introduction of cookies, even though the internet community was much smaller back then. By 1996, the debate in news media and online forums had already led to some changes. Both Netscape and Microsoft added tools to give users some control over cookies.

However, much like today, privacy-invading cookies were accepted by default, and users had to make the changes themselves if they wanted more protection or anonymity.

Over time, a range of different types of cookies have been developed:

Session cookies vs persistent cookies

Session cookies only last as long as the current browsing session. Also known as non-persistent cookies or in-memory cookies, they are deleted from your web browser as soon as you hit the little X in the top right corner.

Websites insert them into your browser when you land on their site, then update them as necessary when you move from page to page. Traditionally, session cookies were used in things like shopping carts, and they could keep track of your intended purchases as you traveled across the site. As soon as you closed the window, whether you bought the items or not, your session cookie would disappear from your browser.

If you returned to the website, the session cookie would no longer be there. This means that even if you hadn’t completed your purchase, there would be no way for the site to know which items had been in your cart. You would have to start shopping all over again.

By their nature, session cookies tend to be benign. You can’t be tracked across the web by something that’s deleted when you close the window. Sure, the website you’re on will be able to track your actions within the website during a session, but compared to other forms of online tracking, session cookies are straightforward and transparent. They are also tremendously useful, forming important parts of our online experience.

In contrast, we have persistent cookies, which are saved by the browser even when a tab or window gets closed. Instead of expiring when you click on the X, they are set to last until a specific date or for a set lifespan. This means that the cookie will remain in your browser, and the website’s server will be able to access it each time you interact with the site, up until its expiration.

Persistent cookies allow websites to remember your login information and a host of other data that makes our online lives more streamlined and convenient. However, the fact that they stick around for long periods also opens up the possibility for them to track you. The website you’re visiting will be able to record your activity over time, while other parties that embed their code on the site will be able to track you across the internet.

While persistent cookies certainly have legitimate uses that make our lives much easier, their frequent use for tracking and data collection has given them a bad name.

First-party vs third-party cookies

When you visit or log on to a website, you may expect some of the company’s own cookies as part of the data transaction. These are known as first-party cookies. For example, your bank’s website may plant some of its own cookies in your browser to facilitate secure logins and for other processes. Your favorite news site may have its own first-party cookies that it uses for subscriber-only access, and so on.

While it’s no great secret any more, some people may still be surprised to find out that a bunch of other entities may also be planting cookies in your browser through these very same sites. The cookies from these other entities are known as third-party cookies, and they are all over the internet.

Many of the biggest names in tech—as well as a bunch of names you’ve never heard before—plant their cookies from all over the web, through code that they embed on sites you visit every day. These can be used for enhancing performance, increasing functionality, data collection and targeted advertising purposes, among other applications.

It’s not uncommon for websites to claim their cookies are in place for either of these first two reasons, even when the skeptical among us may really think that the actual motive falls into the latter categories.

For example, The Guardian claims that Google Analytics cookies are used to enhance performance. While this isn’t necessarily a lie—the information gleaned from these can be incredibly useful for improving performance—Google Analytics cookies are also involved in a significant amount of the world’s advertising-related data collection. This isn’t to single out The Guardian as a worst offender, countless websites do the same. It was simply the first example we came across.

Google Analytics isn’t the only major offender out there. Some others that you will run into all over the web include:

- The Like and Share buttons from Facebook and other social media sites that you see on news websites, blogs, and other content providers.

- Comment sections from third-party platforms like Disqus.

- Amazon’s tracking cookies.

- Google’s DoubleClick.

One of the major concerns related to third-party cookies comes from organizations such as those listed above, which have large networks of them across much of the internet. If a company has its cookies on most of the sites you visit throughout the day, it can effectively track much of what you do online, even if it’s some organization you never notice while you’re browsing, and you’ve never even heard of its name before.

The history of third-party cookies

The fears of tracking from third-party cookies are far from new—they’re almost as old as cookies themselves. All the way back in 1995, a Dutch computer scientist named Koen Holtman warned the IETF task force responsible for the cookie specifications about what was going to happen. He realized that companies could agree to place cookies across a network of websites, share the information, and then track users as they traveled across sites within the network.

In a letter to the task force, he stated:

”Someone is bound to try this trick, and it will, when discovered, generate a lot of bad publicity for the whole Web.”

But the earliest plans that helped turn the internet from a relatively anonymous experience into a hyper-surveillance reality were already underway. The idea behind the advertising network was already being worked on, and by 1996, DoubleClick was using third-party cookies to track site visitors across its platform.

In the intervening decades, the use of third-party cookies exploded alongside the general growth of the internet.

While third-party cookies have long been a privacy nightmare, the good news is that those dark days are almost behind us. By 2020, both Safari and Firefox were blocking third-party cookies by default. Google has configuration options that allow users to disable them, and currently plans to deny access by default before the end of 2022.

While this is a huge step for online privacy, internet users shouldn’t let out sighs of relief too soon. There are still a bunch of other ways that your online activity is tracked, including first-party cookies.

Other types of cookies

There are a number of other types of cookies, however, they aren’t as well known. These include:

- Same-site cookies – These were introduced by Google Chrome in 2016, with an attribute of SameSite, which can be set at None, Lax, or Strict. When set to Strict, they block cross-site request forgery attacks, because this stops browsers from sending cookies when third-party websites request them. When set to Lax, cookies aren’t sent for cross-site subrequests such as loading third-party frames, but they are sent when following a link. None allows cookies to be shared with third parties. As of 2020, Chrome set the default to LAX, as did Mozilla Firefox and Microsoft Edge.

- Secure cookies – When the Secure attribute is included in a cookie, it will only be sent over HTTPS connections. It will not be sent over unencrypted lines, which helps to reduce the risks of eavesdropping.

- HTTP-only cookies – HTTP-only cookies are marked with a HttpOnly flag. This means that they can’t be accessed by JavaScript and other client-side APIs, removing the threat of cross-site scripting attacks.

- Supercookies – These technically aren’t cookies, but they do share some similarities. While normal cookies are stored locally on devices, supercookies are placed at the network level, often by an internet service provider. These cookies can track an internet user’s visits to unencrypted websites and slowly build up a profile from this activity. Carriers could sell this data to advertisers, while websites get access to the supercookie tracking headers every time the user makes a HTTP request. Supercookies can also leak users’ private data, because it is stored in plaintext. In 2016, Verizon was fined $1.35 million for using supercookies to track user activity without their knowledge.

- Zombie cookies – These cookies can be recreated even after they are deleted, through backups either online or on a person’s computer. This allows a person’s web activity to be tracked, even if they use different browsers. There’s even the potential for zombie cookies to spread across devices if a user tethers their mobile to their computer. Even if aspects of these cookies are deleted, they can reproduce, and the web server will be able to access data such as previous user identification numbers. They can then use this information to continue tracking a user’s web activity.

- Evercookies – Evercookies are a type of Zombie cookie that was developed in 2010 by Samy Kamkar. They showed that a JavaScript API could be used to reproduce cookies, even after they had been deleted. When an internet user’s web browser visits a website that features an evercookie API, the server will generate a unique identifier and insert it in various storage mechanisms. These include standard HTTP cookies, Flash cookies, Silverlight Isolated Storage and many other places. Users may delete some of these stored identifiers, but if any remain, the website will still be able to identify the user when they revisit. It will also be able to restore the identifiers to each of the areas that it was deleted from.

While many people only hear about the bad sides of cookies, they are also incredibly useful and form a fundamental part of our everyday online experience. While the harmful tracking and other negative applications get far more attention in the media, the code underlying them is agnostic. The reason they have such a bad name is that the helpful implementations aren’t anywhere near as interesting—it’s the sinister uses that get the headlines.

Customized settings

Do you like your websites to be able to remember your username and password? How about the colors and layout you choose for some of your frequently used pages? Or even the number of search results you like your search engine to include on each page?

Cookies can accomplish all of this, and much more. When you visit a website for the first time, a cookie is inserted into your browser. If you change any settings on the site, these details can be added to the cookie. The webserver encodes these new preferences into the cookie, then sends it back to your browser, The next time you visit the site, the settings are exactly how you like them to be.

By enabling us to customize pages, cookies can give us the web experience we want, as well as a greater degree of convenience. Think of all the time you must have saved over the years by not having to reenter certain fields of data. It’s all because of cookies.

Session management

Cookies are also an important part of logging into websites and staying logged in while you navigate across the site’s various pages. When you arrive at a login page, you will generally be sent a cookie that contains a unique identifier for the session.

If you enter your password correctly, the server remembers this identifier and authorizes it to have access to the website’s services. The identifiers stored in the cookie on your browser facilitate your seamless navigation, while still keeping the website and your account secure. This system allows you to move through a website’s restricted areas, continuing to grant you access until you either log out or the session expires.

In the earlier days of the internet, cookies were also used in ecommerce to store transaction data, such as the items a user had placed in their cart. However, most websites now use databases on their servers to store this information.

Online tracking

Cookies are one of the many mechanisms that can track us across the internet. As we mentioned earlier in the article, session cookies expire after the session, so they aren’t used in the more pervasive types of online tracking. Persistent cookies are the ones we have to worry about. While first-party cookies can help a company track your activity across their own website, these aren’t seen as the worst offender.

The biggest worries are the vast networks of third-party cookies that can track you from site-to-site, building up detailed profiles of your internet activity over time.

If you were to visit a news website, go to a social media platform, then delve into a forum for one of your hobbies, before heading to an online store, you might expect all of the information you provided to stay separate. The odds are that it isn’t, and networks of third-party cookies are just one way that this information could be collected and bundled together.

When you go to that news site at the beginning of your session, your browser sends out a request to the site’s server. If this is the first time you are visiting the site, or you have deleted your cookies since the last visit, the server will create a unique identifier, and send it to your browser as part of the cookie.

This first-party cookie, the website’s own, allows the site to track you across its pages. The next time you visit the website, your browser’s request will include this cookie and its unique identifier. This tells the site that it is the same person from the previous session, and it will add activity from the current and future sessions to what it has already collected from the last one. The URLs of the requested pages, the time of the request and the unique identifier are stored in a log file on the server.

Over time, these log files can build up significant amounts of data about what you accessed, when, and for how long. This information may not seem like much, but over time, it can turn into a highly detailed profile of the individual. But vast networks of third-party cookies can collect an even more worrying amount of data.

When you visit your favorite news website, it’s unlikely that the publisher’s first-party cookies will be the only ones inserted into your browser. A bunch of advertising networks, tech platforms and others have probably embedded their code on the website’s page as well. If this is the first time any of these parties have seen your browser (or the first time since you deleted your cookies), they will also insert their own cookies onto it.

Unless you delete them, not only will these third-party cookies be used to track your activity on the news website, but they will also be used to track you whenever you bump into the same embedded code from these organizations in the future.

Let’s call one of these ad networks Privacy Invader. Privacy Invader will put its cookie on your browser alongside all of the others, then keep track of which pages you access on the news site, what time you visited them, and for how long. Let’s say you really love dogs, and check out an article or two on some celebrities who got new dogs. All of this information goes straight into the log file stored on Privacy Invader’s server.

You get bored, then decide to visit a social media website. As you access the social media platform, a bunch more cookies get added to your browser, both first-party and third-party. But Privacy Invader is there too. Maybe it’s just by chance, maybe it’s because Privacy Invader is pretty much everywhere—it doesn’t matter much.

This time, Privacy Invader sees that you already have its cookie, so it doesn’t add a new one to your browser. Instead, it recognizes you from the unique identifier in the existing cookie, then tracks your activity on the social media platform. Let’s say you visited a few different pages, including some about training dogs. It adds all of this data to the log file on its server.

The forum you visit is also about dogs, and you spend some time looking into optimum diets. You guessed it, Privacy Invader is there too. It sees the cookie in your browser, then adds all of this new activity to the log file on its server once more.

Finally, you make your way to an online store and look at dog collars, water bowls and toys. Ultimately, you decide not to pull the trigger and buy the items, telling yourself that you’ll think about it for a while instead. But Privacy Invader is there too, and because it sees the same identifier in its cookie, it knows who you are. It also knows just how interested you are in dogs, and figures that you are an easy mark.

The whole next week, it constantly advertises dog products to you, in the hopes that you will finally give in and make that purchase. Of course, this is in addition to recording data from all of your new web activity.

The above example is pretty simplistic and low stakes, only covering someone’s internet history for a short period of time. Most of us have been getting tracked by these third-party cookies our entire online lives. We’ve left behind huge profiles that include our hobbies and interests, our political leanings, buying patterns, and much more. It’s an incredible amount of information that can be used to manipulate us into buying things, or even who to vote for.

But it goes far beyond whichever platforms track us. This data is often for sale, and can potentially be stolen by hackers as well. It’s not limited to uncontroversial subjects like dogs, either. Consider looking up sensitive political topics. If you are an activist or live in an authoritarian country, having this information stored in a permanent and ever-growing profile could ultimately be used against you.

In essence, third-party cookies can track your entire online world, producing incredible amounts of intimate data, which you have no control over. Thankfully, we should see the end of third-party cookies in the coming years, but this by no means indicates that we will stop being tracked in such an invasive manner.

Cookies aren’t always bad, so you don’t have to avoid them in circumstances such as when they are used for session management. However, you may want to know how you can avoid being tracked by cookies with more sinister intentions. There are a range of different techniques and mechanisms, but it isn’t necessarily practical to eliminate all tracking from cookies.

The tech industry has been turning against third-party cookies, so these are actually pretty easy to avoid these days. The latest versions of Safari and Firefox already block third-party cookies by default. If you use one of these browsers, you don’t have to do anything to put a stop to third-party cookies. If you don’t already have the latest versions, you should update them anyway, because the latest releases protect you from any recently patched security vulnerabilities.

Blocking third -party cookies in Microsoft Edge

While the latest version of Microsoft Edge offers some tracking protections by default, it does not block all third-party cookies. Either of the previously mentioned options are better for your privacy, but if you insist on using Microsoft Edge, you can block third-party cookies by first typing edge://settings/privacy into the address bar.

Once you arrive at the tracking prevention page, click Strict on the right side. To completely block third-party cookies, click the More Actions button in the top-right corner. Then click Settings. Select Site permissions, then click on Block third-party cookies.

Blocking third-party cookies in Google Chrome

Google Chrome also lags behind in the privacy protection department. Although it will be completely blocking third-party cookies within the next year or two by default, it does not currently do so. Again, Firefox and Safari are better options if you have privacy concerns, but if you are hesitant to change, you can still block third-party cookies by changing the settings.

In Chrome, click on the three dots in the top right corner, then select Settings in the menu that pops up. Under Privacy and Security, click on Cookies and other site data. Select Block third-party cookies.

Blocking third-party cookies on mobile

The recent versions of Safari on iOS and Mozilla Firefox’s app block third-party cookies by default. If you want to block third-party cookies on Chrome in Android, open the app, then click on the three vertical dots to the right of the address bar. In the menu that opens, click on Settings, then on Site settings. Go to Cookies, then uncheck the box that says “Allow third-party cookies”.

If you use Samsung Internet, you can block third-party cookies by opening up Settings and then clicking on Apps within the settings menu. Scroll until you find Samsung Internet, and click on the cog next to it. In the new menu that opens up, go down to Privacy and Security, which is under Advanced. Click on Accept cookies, and you should see a toggle next to Allow third-party cookies. Slide this to the off position to block them.

First-party cookies are often more benign than their third-party counterparts. Many of them don’t track you at all, and they can also be integral parts of a website’s functionality. However, first-party cookies can be involved in tracking as well. When you visit Spotify, Slack, Gmail, or the bulk of other major sites, you will still run into their own first-party tracking cookies, even if you have third-party cookies turned off.

This is because data is everything to these companies, and they seem to rarely miss out on a chance to collect more of it. While blocking third-party cookies will prevent other entities from tracking you on these sites, it does not prevent the sites themselves from tracking you.

You can block first-party cookies as well, but it isn’t as straightforward as blocking third-party cookies. As we mentioned earlier, they are critical parts of a lot of websites, which means that blocking them may break sites or reduce some of their functionality.

Mozilla Firefox

To block all cookies in Firefox, go to the menu in the top right, then click on Preferences. From there, click on the Privacy and Security menu on the left side. Under Enhanced Tracking Protection, click the third option, Custom. Check the Cookies box, then select the last option in the dialogue box next to it, All cookies (will cause websites to break).

As stated, some sites and functions won’t work properly once you have done this. You can add in exceptions for the websites you need by scrolling further down on the Privacy and Security page, until you reach the Cookies and Site Data section. Under this, click on the Manage Exceptions button.

In the display that pops up, you can type any website’s URL into the Address of website bar. Then click the Allow box, followed by Save changes.

Safari

From the Safari app on your Mac, go to Preferences, then click on Privacy. Where it says Cookies and website data, there will be a checkbox, followed by Block all cookies. Click this box. Apple will warn you that this may break websites.

Google Chrome

In Chrome, click on the three vertical dots in the top right corner. Then select Settings. Go to Privacy and Security. Then click Cookies and other site data. Select the Block all cookies (not recommended option). Google does not recommend this, because it will stop many websites from working properly.

Microsoft Edge

Open Microsoft Edge, then type edge://settings/content/cookies into the address bar. On the page that comes up, the first option says Allow sites to save and read cookie data (recommended). If you flick the toggle to the right to the off position, it will block all cookies. However, it will break sites as well.

As we mentioned, completely blocking first-party cookies may not be the best solution, because it will break a lot of websites and complicate your browsing experience. However, there are other ways that you can limit tracking from first-party cookies, without ruining your experience on the websites you frequently access.

But first, we need a better understanding of some of the sneakier types of tracking that are going on. As the world trends toward granting users more privacy, ad tech platforms have seen the writing on the wall. They know that third-party cookies are dying, and have been looking for other tactics that give them similar amounts of data. Some of these include:

CNAME Cloaking

When you block third party cookies, other entities can no longer simply plant their tracking cookies into your browser whenever you encounter them. But they can do something very similar, and it often only requires a little bit of pleading to the website’s owner.

Let’s use an example to show what many ad tech platforms have been doing to combat the changes.

yourfavoritewebsite.com used to have Privacy Invader’s code embedded in the site, which allowed Privacy Invader to directly plant it’s third-party privacyinvader.com cookies into the browsers of those who visited yourfavoritewebsite.com. Privacy Invader had these trackers on websites all across the internet, so it could easily track people and build elaborate data profiles as they moved around online.

Lately, Privacy Invader has been collecting far less user data from yourfavoritewebsite.com, because many people have switched to browsers that block Privacy Invader’s third-party cookies.

But Privacy Invader makes a whole lot of money from this data, so it isn’t just going to slink away with its tail between its legs, admitting that it has lost the battle over data collection. Instead, Privacy Invader sends an email to the owner of yourfavoritewebsite.com:

Hey yourfavoritewebsite.com,

You may not have heard, but there have been some big changes online. Web browsers are blocking third-party cookies, which some say will be better for user privacy, but it will also have big impacts on your business. Based on our studies, you could lose 15 percent of your sales and 20 percent of your audience.

Doesn’t sound good, does it? Don’t worry, we have a solution for you, and it will only take a couple of minutes of your time. All you have to do is embed a first-party tracker at randomsubdomain.yourfavoritewebsite.com, and point it to privacyinvader.com with the CNAME metric.privacyinvader.com.

If you do this, together we will both be able to analyze your visitors carefully and navigate this new landscape, without your business suffering from the changes made to third-party cookies.

Yours sincerely,

Privacy Invader

A CNAME is a Canonical Name Record, which maps one domain to another in the Domain Name System (DNS). In the hypothetical email above, Privacy Invader is essentially asking yourfavoritewebsite.com to use CNAME to make Privacy Invader’s tracker look like a first-party cookie. This technique is known as CNAME cloaking.

CNAME cloaking is able to circumvent techniques that block third-party cookies, because it disguises them as first-party cookies. Unfortunately for the privacy-conscious among us, many websites have adopted CNAME cloaking, allowing trackers to continue their pervasive activities, despite the changes to third-party cookie policies.

How to mitigate CNAME cloaking

You may be surprised that marketers found such an easy way to get around third-party cookie blocks. However, the huge amount of money involved in the data collection and advertising industry creates a significant incentive for the major players to come up with circumvention methods.

At the time of writing, there is at least some good news in the realm of CNAME cloaking. In November of 2020, Apple upgraded its Intelligent Tracking Prevention System (ITP) in Safari 14 on MacOS Big Sur (but not the other versions), as well as iOS 14 and iPadOS 14.

The latest version of ITP can detect third-party CNAME cloaking requests, and makes them expire within seven days. Under other circumstances, these cookies may last for up to two years. Under the shorter duration enforced by Apple’s update, it significantly cuts down on the amount of data that these companies can collect on users.

Firefox does not currently have any of its own mitigation strategies against CNAME cloaking, however it can be configured to CNAME-uncloak network requests with the uBlock Origin add-on. This helps to reveal and block ad trackers that use CNAME cloaking to disguise their third-party cookies.

The Brave Browser was actually the first to introduce CNAME cloaking mitigation mechanisms. It checks to see if network requests have a CNAME record, and blocks requests that would have also been blocked under the canonical domain.

Given that Microsoft Edge and Google Chrome have made limited attempts to prevent the most basic privacy issues associated with third-party cookies, it’s best to stay away from these browsers if you want to mitigate CNAME cloaking.

Bounce tracking

Ad tech companies went into overdrive when browsers started to announce they would block third-party cookies. They didn’t settle on just one circumvention technique like CNAME cloaking. Instead, they also began implementing bounce tracking on a much wider scale.

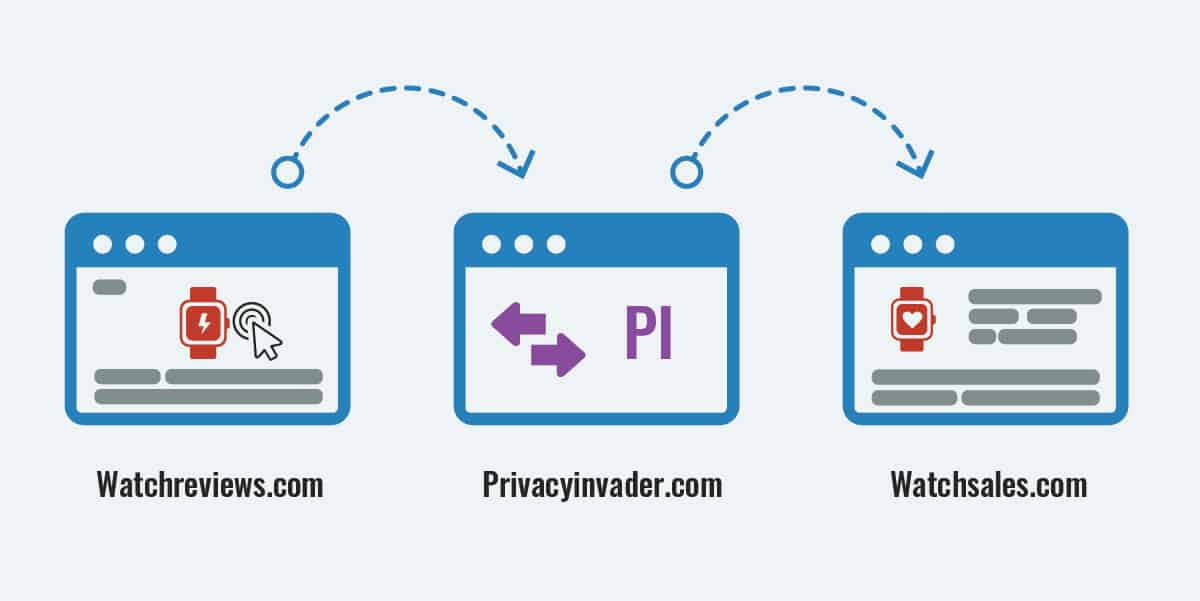

Also known as redirect tracking, bounce tracking is best explained with an example. Let’s say that you were looking at a review site for watches, called Watchreviews.com. You found one that you wanted, and clicked on the link to take you to the retailer’s website, Watchsales.com, so that you could buy the watch. You didn’t notice anything strange, but in between, you were tracked, even though you have third-party cookies blocked on your browser. So what happened under the hood?

You clicked the link on the watch review site, its URL even said watchsales.com, so it’s not as though you were duped into clicking on the wrong site. What really happened, is you were the victim of bounce tracking. Watchreviews.com had a redirect tracker from Privacy Invader embedded on its website. When you clicked on the link to watcchsales.com, the embedded code redirected you to privacyinvader.com, and saved the link to watchsales.com.

Sites that embed bounce tracking code will redirect you to the tracking site without your knowledge or you consent. Once the tracking site gets the data it needs to track you, it quickly sends you on to the page you were trying to reach.

You arrived at privacyinvader.com, and guess what? Since you were on its website, your browser would therefore consider privacyinvader.com to be the first party. Because your browser wasn’t set to block first-party cookies, it would allow Privacy Invader to plant its cookie. The cookie features a unique identifier, which Privacy Invader would associate with a log file on its server. This log file records details about which website you came from, where you were going, as well as the time of access.

Once Privacy Invader had saved the data it wanted from you, it redirected you to watchsales.com, so that you could buy the watch. All of this can happen in just a few seconds, so you probably wouldn’t have had any idea that you had been redirected to a tracking site on your way between watchreviews.com and watchsales.com.

On future occasions when you get redirected to privacyinvader.com as part of a bounce tracking scheme, Privacy Invader will see the session identifier in the cookie , and will be able to add new details to its log file. Through bounce tracking, Privacy Invader can build up a detailed profile on you, even when third-party cookies are blocked.

Mitigating bounce tracking

In 2020, Mozilla Firefox introduced Enhanced Tracking Protection 2.0 (ETP), which includes mitigation techniques for bounce tracking. ETP 2.0 clears out cookies from any known trackers once every 24 hours, which prevents ad tech companies from being able to use bounce tracking to build up large data profiles over time.

While Apple’s ITP first came up with bounce tracking defenses in 2018, it upgraded them even further in November 2020. As a feature of this update, whenever Safari detected bounce tracking, it would prevent the tracker from being able to see the cookies on the internet user’s browser.

Once again, it doesn’t seem like protecting users from bounce tracking is a big priority for Google Chrome or Microsoft Edge at the moment, so you should stay away from either of these options if you are concerned about this technique.

Extra steps to limit data collection and tracking

While third-party cookies may be on their last legs, this is by no means an indication that you will stop being tracked online. Instead, advertising budgets will just be pushed toward discovering other techniques that can circumvent whatever protections have been put in place.

Although there are some pushes toward privacy-preserving forms of tracking, it’s unlikely that these will take over in any significant way in the near future. Even with the positive steps we have seen regarding third-party cookies, we’ve still seen ad tech companies put in the effort to get around them, through the likes of CNAME cloaking and bounce tracking.

While blocking first-party cookies may help to put a stop to these types of tracking, it also renders many websites and services unusable. Unfortunately, it’s just not possible to completely eliminate data collection and tracking while still having a relatively normal online experience.

You are tracked in countless other ways, including browser fingerprinting, your IP address, and advertising IDs. If you are serious about limiting the data collected on you, then you need to worry about these tracking mechanisms just as much as your cookies. Taking the appropriate countermeasures against these other data collection tactics will also have a much better cost:benefit ratio than if you completely blocked all first-party cookies.

If you want to start combating these issues, you also need to recognize that the data collection landscape is constantly evolving, and preserving your privacy is a process, rather than something that is ever finished. As soon as a tech company closes off one type of tracking, advertisers will find another way in. Their businesses depend on it.

Many small steps

There are some easy steps that you can take, which stop large amounts of your data from being collected. Simply switching to Safari or Firefox is a great start, because these browsers are far more privacy-focused than the likes of Chrome or Edge.

Another major step is to begin moving away from companies whose business models rely on data collection, such as Facebook and Google. It can be challenging to completely get away from these internet giants, but there are many small actions you can take.

For example, you can lock down all of the privacy settings on these platforms as tightly as possible. You can also stop making new posts on Facebook, and encourage all of your contacts to talk to you on Signal rather than Facebook Messenger. You can switch away from Gmail and start using a service like Proton Mail instead. You can give up Google’s search engine and switch to DuckDuckGo or StartPage. There are countless small steps you can take to slowly move away from these data-hungry providers.

Another critical move is to sign up for a VPN to encrypt your data in transit. For sensitive searches, you can also use the Tor browser. As a daily-use browser, you can adopt Firefox and start to experiment with some of its add-ons, such as uBlock Origin, NoScript and Multi-Account Containers, which give you far more granular control over who can access your data, and how they can go about it.

The online landscape is complex, and protecting all of your data is an almost insurmountable challenge. But many of the individual steps are quite easy, and each one can have a huge impact on how much data various entities can collect. This means that these companies will have far less of your private information, and it will be much more difficult for them to manipulate you.