Dark patterns rule our lives. They influence us into doing things that we may not have done if the patterns weren’t in place.

They can force us to take actions we wouldn’t have otherwise taken, trick us into spending more money than we had planned, or even violate our privacy.

They exist in both the online and offline worlds, but in this article we will mostly be focusing on how they are used in the digital realm, with a particular focus on how they negatively impact our privacy.

What is a dark pattern?

If we stick to the digital context, a dark pattern is a user interface that has been crafted to manipulate users into taking actions that aren’t in their interest and that they wouldn’t have taken otherwise.

Instead, dark patterns often lead them into taking actions that favor the business, such as handing over more of their personal data, or purchasing something that they didn’t actually want.

The creator of the term, Harry Brignull, has since rebranded his website from darkpatterns.org to deceptive.design. The name change is part of an attempt to come up with a more inclusive term for these practices. He defines deceptive design as:

“…tricks used in websites and apps that make you do things that you didn’t mean to, like buying or signing up for something.”

Since the term dark pattern has more traction and the two definitions are much the same, we will stick to calling them dark patterns throughout the article.

How do dark patterns influence us?

Dark patterns exist on a spectrum, and how menacing an individual pattern is will depend on your own perspective. In some instances, they can be viewed as clever marketing, while others are little more than scams.

When you really boil them down, dark patterns involve the owners of a website or an app trying to nudge people in a certain direction.

The simple fact is that we aren’t as in control of our actions as we like to think we are. We may think that everything we do in life is the result of choices that we have carefully made, but is this really the case?

Anyone who has fallen for the old, “would you like to supersize your meal?”, only to end up feeling bloated and questioning their life choices may already have an inkling that we aren’t as in control as we want to be. Why would we order so much extra food when we know it would make us sick? Why did we change our mind at the last minute and agree to supersize, when we only wanted a medium?

Unfortunately many of our decisions aren’t carefully rationalized, and we can be influenced by these simple nudges. We don’t do a pros and cons list for every choice that we make, and we often just go with whatever is convenient, easy, or whatever everyone else is doing.

Sometimes, these nudges may be in an attempt to accomplish something that many would view as positive. One example would be changing a country’s default organ donation policy from requiring people to voluntarily opt-in, to signing them up by default.

When people have to make the effort to opt in for organ donation, it’s theorized that fewer people will bother signing up, meaning that there will be fewer organs in the pool for needy recipients. By changing the default to opt-out, it’s hoped that only those who are truly against donating their organs will make the effort to back out from the pool, resulting in increased organ donation rates.

At other times, it’s more sinister, such as:

- When a company tricks you into paying extra.

- A developer fools you into installing a toolbar you didn’t need.

- An app makes it really hard for you to use without handing over your phone number.

Let’s jump into an example to show you how these dark patterns can lead to negative privacy outcomes for users.

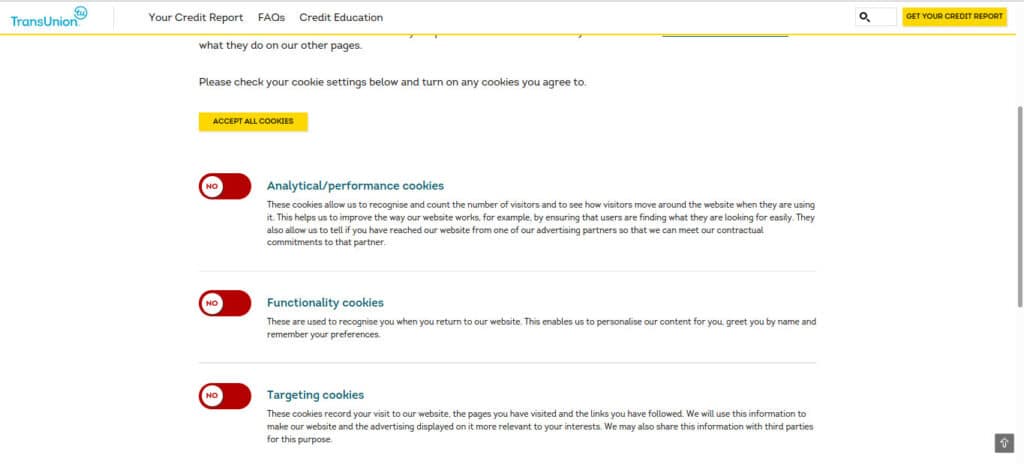

Dark pattern example: TransUnion

Let’s say you are visiting the UK website for TransUnion, a credit bureau. You go to check your cookie settings, and as a privacy-concerned individual, you want to opt out of all unnecessary cookies. So what do you do? You make sure that each of the toggles are set to “NO”:

A screenshot from the TransUnion Bank cookie page.

Then you go to save your settings by clicking the big yellow button. Wait a minute, look closer. The yellow button actually says “ACCEPT ALL COOKIES“. If you click on it without paying too much attention, you will have accidentally toggled each of the three cookie options to “YES”.

TransUnion isn’t technically lying to us, but it is taking advantage of our intuition and deliberately setting up its interface in the hopes that we will make a mistake. TransUnion is trying to take us through a dark pattern.

You can visit the Sightings page on the Dark Patterns Tip Line for more examples of dark patterns.

Types of dark pattern

There are a wide variety of dark patterns. Some of the most common ones include:

- The roach motel — This pattern refers to situations where it is easy to enter, but hard to get out. A good example is when you can easily sign up via a web form, but when you want to cancel, you have to call and spend 40 minutes listening to elevator music before a pushy sales agent tries to guilt you into staying. The name is derived from an old ad for a cockroach trap, which had the tagline, “Roaches check in…but they don’t check out”.

- Confirmshaming — This tactic involves playing the guilt trip when a user opts out or declines something. You may have seen these snarky messages in situations like when you unsubscribe from an email list. It’s often something along the lines of “Oh, we’re so sorry to see you go, the rest of us will be having so much fun without you.”

- Friend spam — Under this technique, a social media service asks for you to alter your permissions or hand over your email, with some vague message about how it will help you find friends or build your network. It then goes on to spam them with messages without your permission. A classic example is LinkedIn’s early UX, for which it ultimately ended up paying a $13 million fine.

- Trick questions — When the interface phrases a sentence in an unintuitive way, leading to users accidentally entering information that goes against their wishes. A good example would be if you were signing up to an account and came across a checkbox that said something along the lines of, “Do not stop sending me new marketing emails.” Users who are accustomed to similar messages may overlook the “stop”, and end up accidentally signing up for the emails.

- Sneak into basket — In an online store, the website may sneak an additional product into your cart against your wishes. At some stage during the checkout process, there may be a popup or camouflaged checkbox that adds something you did not intend to buy.

- Privacy zuckering — Manipulating users into sharing more of their information than they originally intended. Named after the king of the practice, Facebook’s Mark Zuckerberg, privacy zuckering often uses complex options that confuse people into handing over more of their personal data.

- Forced continuity — Have you ever signed up for a free trial, only to forget about canceling it? All of a sudden, you may be charged hundreds of dollars, while you thought you were only committing to a free trial. This is a case of forced continuity, and it relies on hidden fine print that tricks users into signing up for the product.

- Misdirection — This tactic involves an interface that is designed to purposefully focus your attention on one thing in order to distract you from another important aspect. deceptive.design uses an example from the Australian low-cost airline, JetStar. During the checkout process, a seat is automatically chosen for you, adding an additional cost of $4.50 each way. The surrounding design is loud and overwhelming, with options to pay for additional packages at the top of the page, easy for a user to click on. But if a user wants to avoid paying for seat selection, they have to find a tiny button at the bottom that says “Skip seat selection”. Websites deliberately make it hard for users to find their ideal outcome, and instead they prominently display the choice that is in the company’s favor. This technique overlaps with false hierarchies, where websites often construct their interface to lead users into acts that favor their ideal outcome. A good example involves the “Accept All Cookies” button being shaded a vibrant blue, while the option to opt out is in gray.

- Disguised ads — These are ads that camouflage themselves as some other type of content or even part of the navigation. deceptive.design has a good example of this from Softpedia, a website where users often go to download software. When the users arrive at the page, they will see ads that are pretending to be the download button. These trick visitors into clicking on them, which ultimately leads to them being redirected to an ad site instead of downloading the software that they actually want.

- Hidden costs — The price displayed at first is not the total price that you end up paying. Users will often see a price that appeals to them, click through the various steps to reach the checkout, and then be whacked with extra fees, like service fees, delivery fees, or cleaning fees. Because the users have already put so much effort into each step of the purchase, they often give in to the sneaky tactic and ultimately pay more than they otherwise would have.

- Bait and switch — The interface appears to do one thing, but it actually does something else. A classic example of this is when a popup has an X button in the corner, but when you click it, it actually brings you to a website instead of closing the popup.

- Bad defaults — These are when the default options are against the interests of the user. Instead, they are generally in favor of the company. Examples include when users have to opt out of sharing their data, or go through a bunch of complicated settings in order to lock down their privacy. Unfortunately, this is the norm with many companies like Facebook and Google.

- Intermediate currency — This involves users spending actual money to buy a virtual currency. It dissociates the user from the real dollar value of purchases in the virtual currency, and can lead them into spending more than they otherwise would have. This is commonly seen in in-app purchases and mobile video games.

- Nagging — Nagging is a dark pattern that involves repeatedly asking users for the same thing. There is often no option to make it stop, with the hope of eventually breaking users and getting them to agree. We commonly see this with websites asking you to download their app, or platforms asking you to give them your phone number for supposed security purposes.

The history of dark patterns

The term “dark pattern” can be traced back to 2010, when Harry Brignull, a UX designer, set up his website, darkpatterns.org. The site began as part of Brignull’s campaign against deceptive design practices in our technology, and it now goes by the moniker of deceptive.design in a bid to add clarity to its focus.

The underlying concepts of dark patterns go much further back, and even predate the internet. A classic example of similar practices in the offline world can be found in pricing.

We’re all familiar with walking into a department store and seeing prices like $19.99 or $189.99. Why don’t they just round it up to $20 or $190 and make everyone’s lives easier?

It’s because research shows that this is an effective method of getting people to buy more. Pricing that ends in 99 tends to trick our brains into thinking that a product is cheaper than it really is, which makes us more willing to purchase it. The stores don’t care about the one measly cent if they can make way more money through increased sales. Given that this tactic essentially involves deceiving our brains about the price, it is a dark pattern.

There are a ton of other tactics in the physical world, like:

- Buy one get one free.

- Limited time only offers.

- Zero down payment, interest free for the first year.

These and other techniques are effective ways of manipulating us into spending more than we otherwise would want to spend.

Most of us are fairly used to these types of tactics and begrudgingly accept them, even if there is a sinister underbelly to them. But as the internet became a greater part of peoples’ everyday lives, these tactics moved online as well and became far more sophisticated.

The digital world ratcheted things up a notch because it gave companies access to more metrics and massively sped up the feedback loop.

Through tactics like A/B testing, businesses could quickly figure out the best ways to convince users to take the actions that favored the company, whether it was to buy their product, or give them their data.

Let’s say a company wanted to increase their sales in the olden days. They might put up a billboard, and then see how sales went over the next few months. One of the problems with this is it takes a long time to notice whether or not there has been an uptick in sales.

Another issue is that it’s hard to attribute whether the extra sales are because of the billboard or some other unknown factor. Maybe the economy is just doing better? Perhaps it’s word of mouth is increasing sales? Maybe a competitor’s product has gotten a lot worse and customers are turning elsewhere?

The point is that it used to be really hard to tell whether or not a tactic was actually helping to increase sales.

A/B testing

All of this changed in the online world, with the likes of A/B testing and other techniques, because they gave companies almost immediate feedback on whether or not something works. A/B testing is also known as multivariate testing.

In short, an organization begins by defining its end goal. In this case, let’s say that it wants more users to accept its tracking cookies so that it can follow them around online.

The next step is to run an experiment. To keep things simple, let’s say that a company wants to know which of the following will be more effective for getting people to accept their cookies:

Would you like to run our cookies so that we can spy on you online?

Or:

Would you like to run our cookies to enhance your online experience?

The company then splits its website visitors up into two groups, with half receiving the first message and the other half receiving the second. After a statistically significant number of users have seen each message, the company then crunches the numbers.

Let’s say that only one percent clicked “Accept” for the first message, while 50 percent clicked “Accept” for the second.

The company has tested which of the two messages works best, A or B, and gotten an incredibly clear result. Going forward, it will only display the second message so that more of its visitors will accept its cookies

Of course, not every A/B test is so obvious. Businesses can run these tests on just about everything, from which fonts are more effective in getting the results that they want, to whether the “Accept” box should be shaded blue, or the “Deny” box should be shaded instead.

If an organization does these tests again and again, to every element of the user’s journey through their website or app, they can optimize every single component to make users more likely to pursue the organization’s desired course of action. In our example, they can try every possible configuration and figure out the most likely setup to convince users to accept their tracking cookies.

User experience (UX) and dark patterns

Now we come to a very important question:

Are user experience (UX) designers evil?

It’s a bit like asking whether all advertisers are evil. Advertising on its own is neutral. No one would say that an ad campaign against drunk driving is evil, but we all agree making a cigarette ad that appeals to kids is.

UX is the same. When it’s done well, it’s amazing, and it can make a user’s time in an app so much easier and more enjoyable. When it’s used deceptively to work against the interests of users, then it can be unethical.

At its core, user experience is the interaction between users and the service, system or product that they are using. The field is particularly concerned with the usefulness, efficiency, ease and simplicity, as well as how a user feels about the interaction.

As users, we want whatever we are interacting with to bring us toward our goals as smoothly as possible. In an ideal world, we want our website and app developers to make it as simple and straightforward as they can for us to complete our desired actions.

To give you a good understanding of the importance of good user experience, let’s take you back to a world before UX was a major consideration in the development of websites:

https://www.cameronsworld.net/

If you clicked through the link, you would have been brought to a conglomerate of abominations, a collection of Geocities sites. While some of us may feel a little nostalgic for them, they are objectively painful to look at, and make it difficult to navigate and find the information we are looking for.

If you want to jump forward in internet history, you can compare the mess that was everyone’s customized MySpace page against Facebook’s relatively clean, consistent and easy-to-use interface. While it’s hard to say conclusively, many have posited that UX played a role in Myspace’s death.

So good UX is important from both a user and a business perspective. Good UX helps us get what we want as simply as possible, and all else being equal, a company with better UX will likely attract more users.

But what happens when the interests of the users and the company diverge?

This is where we get dark patterns.

When companies and users both want the same thing, there’s no need to employ the deceptive tactics of dark patterns. No manipulation is necessary, all the company has to do is provide the desired service or product.

Let’s investigate the underlying conflict between businesses and customers through an example.

Hot dogs and dark patterns

If we have a hot dog stand and can make a decent profit by selling hot dogs for $5, we can simply put up a sign that says “$5 hot dogs”. Anyone who walks past who wants a hot dog more than the $5 in their pocket can simply line up and get their hot dog. We get their money, and they get their questionable pork meat. Everyone is happy. There’s no need to deceive anyone, because the customers want a $5 hot dog.

But let’s say business isn’t doing too great at the old hot dog stand. We decide to change our sign in the hopes of bringing in more customers. We change it to “$1 hot dogs*”. A huge line forms as people rush to get the amazing deal. But once they reach the register, we tell them that their hot dog will be $5.

As a crafty business, we added in the little asterisk, because only the sausage itself is $1. For the bun, the mustard and the relish as well, it’s five big ones. Most people end up paying because they have already lined up. We didn’t quite lie, because we had the asterisk, and we told them before they paid. But every customer leaves with a bad taste in their mouth.

Why? Not because of our tasty hotdogs, but because of the deception.

This is essentially the same underlying problem with dark patterns. Instead of being straight up with us and allowing us to choose what we really want, websites and apps are being sneaky and tricking us into giving them what they want. Whether it’s AirBnB hiding the total cost, or Delta tricking us into spending more money, we feel cheated. We are cheated.

The core of the problem is that the interests of users and companies are often out of alignment. As users, we tend to want a product or service as quickly, cheaply, and easily as possible. On the other hand, companies often want to extract as much from us as they can, whether it’s our money or our data, which they can presumably sell or leverage to make money by some other means.

They can do this in a straightforward way, by clearly raising their prices, or simply explaining the data that they want to collect. There’s no problem with this, because it’s honest and upfront.

The problem comes when they resort to dark patterns. They know that we don’t want to pay above a certain amount, so they just add on an extra fee right at the end, when we already feel committed. Or, they know that we don’t want to hand over our data, so they make it really hard and confusing to opt out.

The real issue isn’t that companies are trying to make money, it’s that they are using deception by deploying dark patterns in order to do so. With tools like A/B testing and others in their hands, they have immense powers that they can use to manipulate users to act against their interests.

Dark patterns and privacy: A case study

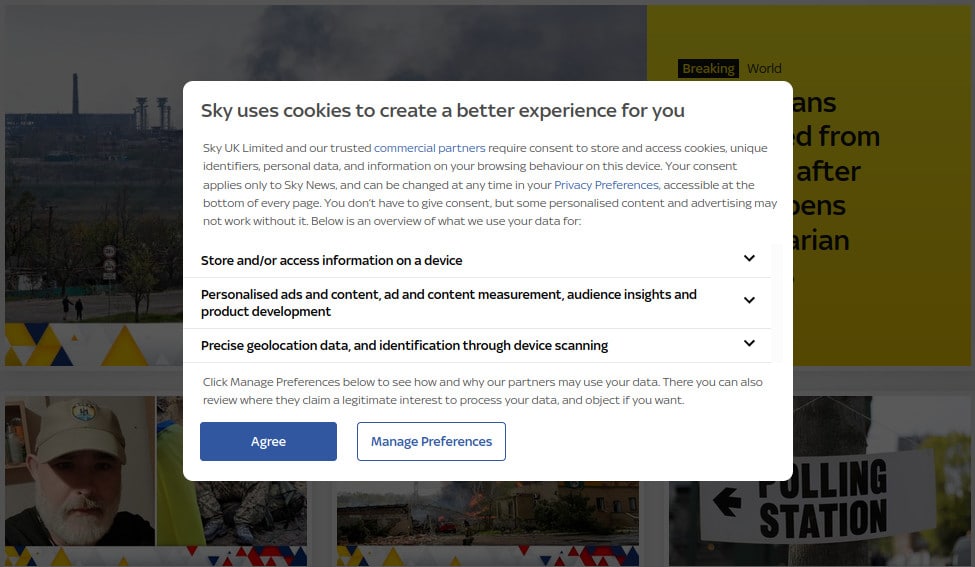

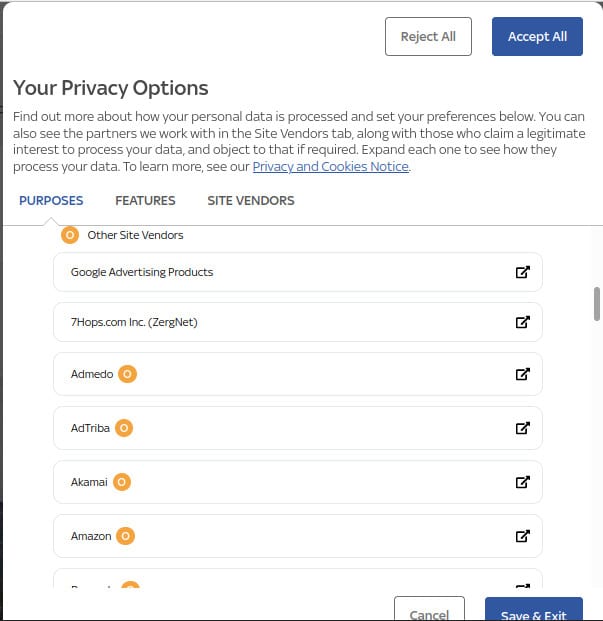

Let’s say your mom, your aunt, your grandfather, or someone you know who isn’t technologically proficient, is on news.sky.com, taking a look at the day’s headlines. They may be greeted by the following screen:

A screenshot of the news.sky.com cookie page.

Whoever it is, they aren’t very tech savvy. They’ve heard a little about cookies, and know that they can have something to do with following them around online.

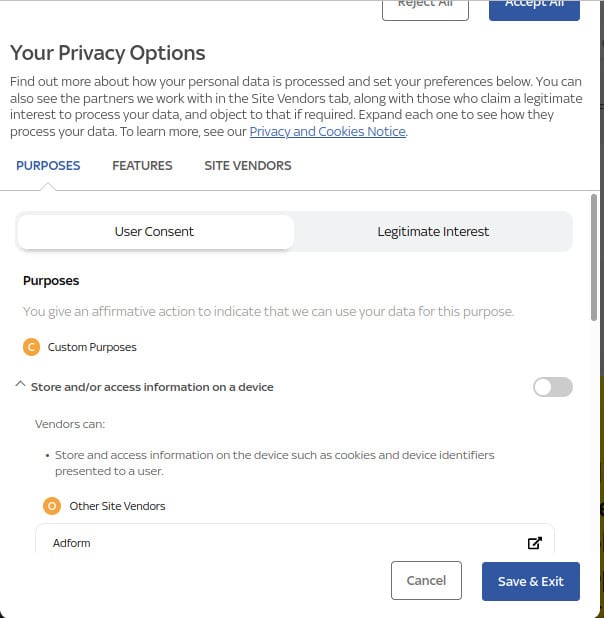

They have a bit of free time to kill, so instead of doing what they would normally do by clicking “Agree“, they click on “Manage Preferences” to try to figure out what’s really going on. It takes them to the following page:

A screenshot of the Sky News privacy options.

This page is a total mess, with options all over the place, a lot of technical jargon, and choices that we have to read again and again to try and understand, things that grandpa just doesn’t stand a chance of wrapping his head around.

We don’t want to bore you with a play-by-play analysis of everything that’s wonky on this page, but let’s start with the first blurb, which includes “You can also see … those who claim a legitimate interest to process your data, and object to that if required.”

What is a legitimate interest?

The first thing that stands out is the term “legitimate interest”. If it’s legitimate, it must be okay, right? Until you back up and reread it again, “…those who claim a legitimate interest.”

The word claim changes everything. We can claim that the flat earth theory is legitimate, but that doesn’t make the claim valid (sorry flat earthers).

But the average person scanning through the options may miss out on these details. Not everyone has as much time to kill as we do. The confusing nature of the page and its language is already making this pattern seem quite dark.

So let’s inspect the “Legitimate Interest” tab and see what qualifies for legitimate in the world of news.sky.com:

A screenshot of the Sky News privacy options.

Under “Purposes”, it says:

“We have a need to use your data for this processing purpose that is required for us to deliver services to you.”

Again, it includes some strong and important words. “We have a need”, and “required”. But when it’s time to discuss the need and the requirements, it uses super generic language so that the user has no idea what it’s talking about. We don’t know what the “processing purpose” is, nor do we know what these services that are being delivered are. But because of the language, they sound important. It must be something that the site absolutely needs in order to function, right?

Underneath this, there’s a “Store and/or access information on a device” option, which seems to be toggled to the on position. If we unfold the menu to see more, we find that:

“Vendors can:

- Store and access information on the device such as cookies and device identifiers presented to a user.”

Cool, but why is this important? Guess we’ll have to dig deeper and click on the first vendor, “Sky”. This takes us on a magnificent journey to the Sky Privacy and Cookie Notice, which is a brief and simple 6,521 words. It’s just some light, Sunday morning reading.

Privacy policy hell

In short, it seems to say that Sky “processes” any information from you that it can get its hands on. It then goes on to describe what it means by processing:

“The main purpose for which we process your personal data is so that we can provide you with content, products and services, in accordance with the contract you have with us (this includes where you have agreed to be part of a trial of our products and/or services). This includes determining eligibility for certain products, services and offers, as well as providing you with account management functionality (such as to update your contact information), processing and collecting payments, customer support (including diagnostics and trouble-shooting), call screening and blocking, and tailored and personalised experience whilst using our products and services such as recommendations for the content you subscribe to (including by sending you newsletters about your service, content and relevant products.)”

It’s not exactly easy to understand what they mean in this section, because they bring up a contract, and we don’t remember signing a contract with Sky. Amid other things, we can only assume that the “content, products and services” and the “newsletters about your service, content and relevant products” refer to delivering ads to us in some way.

When we return to the mystery of what a “Legitimate Interest” is, as far as we can tell, it includes hoovering up all of your information and using it to advertise to you, among other things. This setting seemed to be set to the on position by default. But even after spending hours looking into this, we aren’t too sure what it means in its entirety.

What we do know, is that claiming to use our data for advertising as a “legitimate interest” is a stretch. So how can the average person know what they are getting into? This torrent of confusing language is clearly a dark pattern aimed at beating users into submission.

Wait, did we sign up for a loan?

When we delve further into the privacy and cookie policy, it gets weirder. It starts talking about loan agreements and credit reference agencies. We don’t remember signing up to any loans, but if we accidentally did at some stage while visiting news.sky.com, we may have to skip town.

Maybe this loan stuff isn’t even relevant to the cookie settings on news.sky.com, and it’s just a general privacy policy that includes a bunch of the company’s other services. When they make it so difficult, how are we supposed to know? It’s Sky’s fault for making this all so incredibly complex. It’s too hard for us to understand, so Grandma has no chance.

We can’t bear to go on reading the Sky Privacy and Cookie Notice because we’re worried that the ludicrous complexity may cause a brain bleed. With all this talk of loan agreements and credit services, we’re getting scared that we may have accidentally violated our health insurance just by trying to read the news. Who knows?

But the Sky Privacy and Cookie Notice is just the first of three privacy policies. We don’t hate ourselves enough to look into the other two, but we assume they are much the same. Let’s move on and take a look at the other ways they’re trying to bamboozle us.

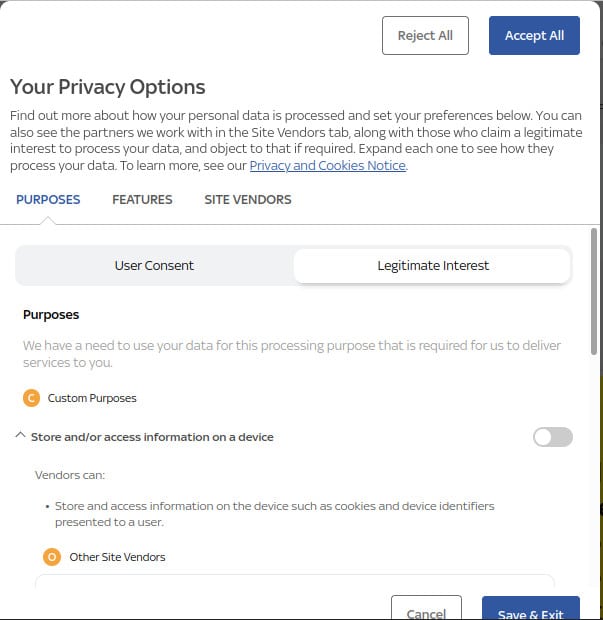

Are personalized ads really “Legitimate Interest”?

Let’s take a look at the next option in the “Legitimate Interest” section, “Personalised ads and content, ad and content measurement, audience insights and product development“. It’s set to “Accept All”.

When we open it up, we find that it lists nine different options, each of which show dozens of advertising-related platforms underneath them:

A screenshot of the Sky news personalised ad options.

Most of these seem to do with personalizing content, which is generally just a euphemism for targeting you with ads. Perhaps targeting you with ads isn’t necessarily such a bad thing, but making it too difficult for any normal person to understand and give informed consent is certainly problematic.

The dark pattern prevails

The news.sky.com privacy options go on and on, and it will get too dull if we go through it all. But the most important point is that we do this kind of stuff for a living and even get paid to read the fine print. But it’s almost impossible, even for professionals like us, to figure out what the cookie and privacy options really mean.

So what chance does your average internet user have, or someone with limited tech skills? They don’t have the skills or the free time to try and figure this all out, so what are they going to do? They will probably opt-in to a data sharing arrangement they don’t actually want, either out of confusion, or simply because it’s easier.

This is a dark pattern, and news.sky.com is far from unique in using them to trick or mislead internet users into doing what is best for the company, even if it goes against the interests of a legitimate internet user.

Dark patterns: But wait, there’s more

The dark patterns on the news.sky.com website aren’t limited to simply making everything too complex to understand. They actually begin much earlier in the user’s interaction with the site.

If you take a look at the first screenshot, you will see that “Agree” is on the left, shaded a deep blue, while “Manage Preferences” is to the right, in a plain white box.

If an internet user stumbled across a page like this and didn’t take the time to read either option, which box do you think they would be most likely to click on?

The left of course. In the English speaking world, we read from left to right, so this is the option we see first. The deep blue color also makes it much more obvious, so our eyes and our cursor are going to be automatically drawn to it. It even uses affirmative language, which we generally like.

Do you think it’s just a coincidence that each of these aspects favor the choice that news.sky.com wants its users to take, and not the choice that is in the interests of users and their privacy?

We don’t.

This is clearly a dark pattern, because the easiest or default option isn’t what is best for users. It’s what’s good for the company and their providers.

In the fast paced world of the modern internet, it’s simply not practical for the average user to understand what is happening, nor could they read all of the fine print. Although they may be given the option, and they may have “consented”, is it really informed consent?

No. It’s manipulation.

Look, we understand that we’ve just droned on for ages about something as dull as the cookie settings on news.sky.com. You are probably bored and half asleep by now.

But this is such a crucial point in how these sites and applications are designed. If they make things long enough, complicated enough and boring enough, you will just give up, quit and just accept whatever they are trying to cram down your throat, just so that you can move on.

This is their tactic. This is how they win and you lose. This is why we had to spend so much time going through the drudgery of the Sky News privacy policy. If we don’t understand their tactics, we can’t out-judo them.

How to fight dark patterns

As we have discussed, dark patterns are a significant issue for internet users and they can compromise user privacy, among many other negative effects. However, there are ways that various parts of the community can fight them:

What can developers do about dark patterns?

If you are a developer, you should think about the possible ramifications of using dark patterns. At their core, they are deceptive. If you implement them on your website or app, you are fracturing the trust between your brand and its customers.

If you’ve ever been frustrated by figuring out the cookie options or angrily called your credit card company after being billed after a “free trial”, you will know what this feels like. You might even carry a grudge against the company forever.

Knowing how these techniques can impact your customers, you should seriously consider whether they are the right move for your company.

The alternative to dark patterns is simple. Just be upfront and truthful. Don’t try to deceive, manipulate or mislead people into doing things they don’t want to do.

It should be simple, right?

Then why do so many major companies still use them?

Because they work, at least in some ways.

Why do developers persist in using dark patterns?

If you, as a developer, want to track your users so that you can target them with ads, you probably won’t get many takers to accept your proposition if you just state it outright.

If you want to maximize the number of people who agree so that you can make more money, you will be far more successful with something euphemistic, something along the lines of “Would you like to allow personalization to enhance your experience?”

It may be deceptive, but it will get results.

While there is certainly truth to this, you also need to consider your brand’s reputation and the fracturing of trust that these deceptive tactics can create.

Good companies with a long-term view of their brand’s reputation may pursue these tactics, but those more focused on quarterly revenue growth may struggle.

Put yourself in the position of a manager who has been told that they need to raise revenues in order to meet their targets. If your job was on the line and you had a handy tool like A/B testing, it may be easy to neglect the ethics of what you are doing, and simply implement whichever dark pattern is most effective to boost revenue.

Of course, the potential for bad PR may weigh into these decisions to some degree, but considering that many major companies engage in dark patterns, the negative effects may be worth the additional revenue gains.

Can we trust developers to stop using dark patterns themselves?

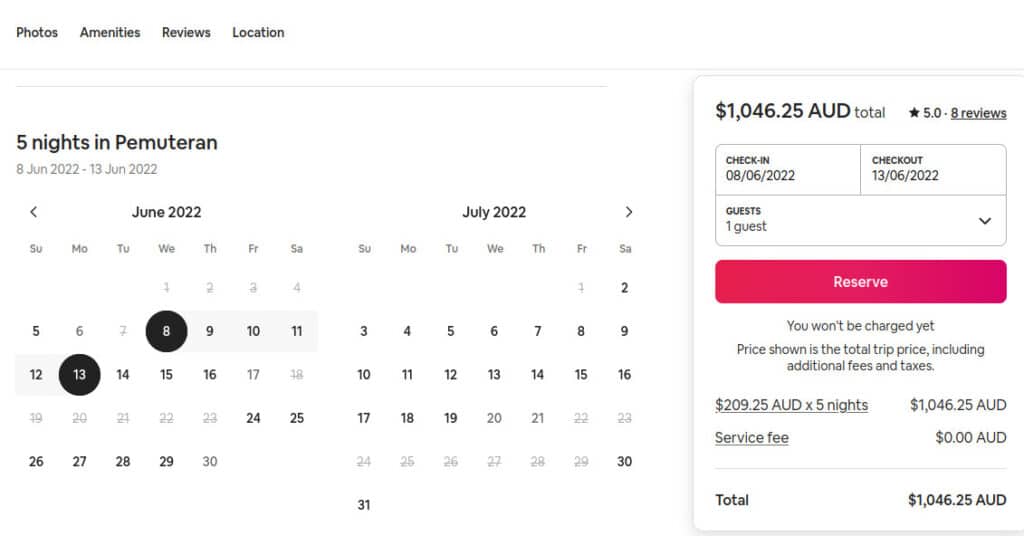

Let’s take AirBnB for example. In many jurisdictions, it lists a nightly price. However, when you click through to book the accommodation, you will see a cleaning fee and a service fee tacked on at the end, which end up adding significantly to the overall cost. This practice is known as drip pricing, which is a dark pattern.

In Australia, AirBnB does not use drip pricing, and instead displays the total cost up front:

The lack of drip pricing on the pricing page on AirBnB.com.au

Guess what? It’s not because AirBnB realized the error of their ways and decided that they need to stop misleading their Australian users. It’s because drip pricing is against Australian regulations.

AirBnB still uses drip pricing in jurisdictions where it can legally get away with it. This is despite the fact that the issues surrounding drip pricing have clearly been brought to the attention of AirBnB executives, and that the company has found a solution for the Australian market that doesn’t involve such deceptive tactics.

Perhaps AirBnB doesn’t care about fracturing the trust between itself and its customers. Or maybe it has just crunched the numbers, and realizes that the amount of money it makes from dark patterns outweighs any negative effects.

While this is just a single example, we could easily come up with countless others. It makes it hard to believe that we can rely on the goodwill of developers to protect us from dark patterns. Instead, a legislative approach may be the only way that we can protect the majority of users.

Legislation

Legislation is challenging, particularly in the tech sector, because laws move slowly, while technology is fast and constantly adapting. When you add in additional factors like lobbying and the fact that many decision-makers lack technological understanding, the path to adequate legislation will be long and difficult.

Despite this, we do have some great examples of where laws have helped to protect users from dark patterns. We just mentioned the Australian regulatory environment that restricts drip pricing. There are a number of other laws that either overlap with dark patterns, or specifically attempt to limit their implementation.

Europe’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR)

Europe’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) is a broad set of rules that include numerous user rights and protections. It doesn’t specifically focus on dark patterns, however, a number of its provisions intersect with them.

Under the regulations, one of the main legal bases for collecting and processing user data is via consent (note that there are other legal bases that do not require consent).

The GDPR defines consent in the following way:

“Consent of the data subject means any freely given, specific, informed and unambiguous indication of the data subject’s wishes by which he or she, by a statement or by a clear affirmative action, signifies agreement to the processing of personal data relating to him or her.”

It goes on to define freely given consent as meaning that:

“…you have not cornered the data subject into agreeing to you using their data. For one thing, that means you cannot require consent to data processing as a condition of using the service”

The definition of freely given consent, plus terms like specific, informed, and unambiguous seem like they should completely outlaw the use of dark patterns for obtaining and processing user data.

Despite this, a 2020 study called Dark Patterns after the GDPR: Scraping Consent Pop-ups and Demonstrating their Influence found flagrant disregard for these aspects of the regulation.

However, there is some hope for better protections against dark patterns for European users. In March 2022, the European Data Protection Board (EDPB) published a draft titled Guidelines 3/2022 on Dark patterns in social media platform interfaces. It aims to help bring social media providers in line with the stipulations set out in the GDPR and limit the use of dark patterns that violate the regulations.

The draft was open for public consultation until the beginning of May, and at the time of writing, we aren’t sure whether it will be finalized or whether the finished version will contain significant changes.

Although the final outcome and any potential impact are still up in the air, the draft includes some promising guidelines:

- It recommends against bombarding users with continuous requests for unnecessary user data like their phone number. Instead, providers need to recognize the GDPR principle of data minimization.

- It recommends against using emotional language to steer users into sharing data like their geolocation, photos or personal data. It gives the following example as a bad practice:

“Hey, a lone wolf, are you? But sharing and connecting with others help make the world a better place! Share your geolocation! Let the places and people around you inspire you!” - It recommends against making the process for opting out of data collection more difficult than the process for opting in.

- It recommends against steering users into handing over data through differences in visual style. As an example, the button to opt out may be gray or harder to read than the button to opt in. Developers should not use practices like this or smaller font sizes to steer users into providing more data.

There are many more similar provisions throughout the guidelines, but again, they are yet to be finalized, and we do not know whether they will actually play a role in diminishing the use of dark patterns.

Other European actions against dark patterns

Although the future of the guidelines is uncertain, there have been some other positive developments. In January 2022, France’s data protection regulator fined Google €150 million and Facebook €50 million. The fines were under France’s Data Protection Act, which implements some aspects of the GDPR.

The two companies were penalized for making it harder for users to opt out of cookies than it is to accept them. In response to the fines, Google is beginning to roll out new cookie permissions that give users a clear “Deny All” button, allowing them to easily opt out. (The link is in French, but in the picture of YouTube’s new cookie settings, you can clearly see a blue button at the bottom which says “TOUT REFUSER”. This translates to “REFUSE EVERYTHING”).

The same regulator also hit Google with a €50 million fine back in 2019 for lack of transparency and valid consent in its ad personalization. In 2020, it was at it again, fining Google €100 million for placing cookies on user computers without first obtaining informed consent.

While these fines may be low for a company as cashed up as Google, they do seem to be steering some change.

California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA) and the California Privacy Rights Act (CPRA)

In 2018, California introduced the California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA), with the aim of boosting privacy rights and consumer protections for Californian’s. In 2020, its provisions were expanded with the California Privacy Rights Act (CPRA).

These laws contain some provisions that legislate against dark patterns. For example:

“A business’s methods for submitting requests to opt-out shall be easy for consumers to execute and shall require minimal steps to allow the consumer to opt-out. A business shall not use a method that is designed with the purpose or has the substantial effect of subverting or impairing a consumer’s choice to opt-out.”

- This explicitly forbids the dark pattern of making it really hard for users to opt out.

“A business shall not use confusing language, such as double-negatives (e.g., “Don’t Not Sell My Personal Information”), when providing consumers the choice to opt-out.”

- This prevents a provider from tricking users into handing over their data.

“Upon clicking the “Do Not Sell My Personal Information” link, the business shall not require the consumer to search or scroll through the text of a privacy policy or similar document or webpage to locate the mechanism for submitting a request to opt-out.”

- This makes it much easier for users to opt out.

“”Consent” means any freely given, specific, informed, and unambiguous indication of the consumer’s wishes by which the consumer … signifies agreement to the processing of personal information relating to the consumer for a narrowly defined particular purpose. Acceptance of a general or broad terms of use… does not constitute consent. Hovering over, muting, pausing, or closing a given piece of content does not constitute consent. Likewise, agreement obtained through use of dark patterns does not constitute consent.”

- This is significant, because it completely invalidates any “consent” that was given through a dark pattern.

Together, these laws are extremely positive for Californians in their fight against dark patterns. Given that many major tech companies are based in California, there is the potential for these regulations to eventually have wider impacts than just in their home state.

The Colorado Privacy Act (CPA)

The Colorado Privacy Act (CPA) is a similar state law that treads much of the same ground that the CCPA, so we will keep our explanation short to avoid too much redundancy.

It follows the CPRA’s definition of consent, including a refusal to acknowledge consent that has been derived through a dark pattern.

There’s also the Virginia Consumer Data Protection Act (VCDPA), but this doesn’t specifically mention dark patterns, so we won’t bother going into it.

How can users avoid dark patterns?

The path toward global, comprehensive legislation against all types of dark patterns will be long and arduous, so we can’t really hold our breath waiting for it. The good news is that there are some things we can do to help us manage and avoid dark patterns.

The bad news is that it may be challenging to get your aunt, your grandparents, and your tech-illiterate friends to jump on board, so they will likely continue to be victims of dark patterns.

Educate yourself on dark patterns

One of the best ways that you can combat dark patterns is to understand them. Websites like the EFF’s Dark Patterns Tip Line and deceptive.design can teach you about the techniques that developers use and show you numerous examples of major websites using them.

Once you are aware of these tactics, you will start to notice them whenever you go online. With awareness, it will be much easier to avoid falling for these tricks.

When you spot a dark pattern, you can also do something good for humanity and report it to either of the above websites. A little bit of pressure may push some of these companies to give up on certain deceptive practices.

Beyond educating yourself, it’s good to always be a little suspicious whenever you are online. If you don’t understand something, try looking it up, or defaulting to “No”. While there have been some minor steps against dark patterns, these sneaky practices are still widespread and pervasive.

Protect yourself with add-ons

When you visit a new website, the dark patterns tend to make it hard to reject unnecessary cookies. Ultimately, this results in many of us being worn down, and simply clicking “accept” so that we can get what we need.

There are a few add-ons that can help to deal with the problem. However, there aren’t really any perfect solutions. On the more privacy preserving end-of the spectrum, add-ons like Ninja-Cookie, Cookie Block and Consent-O-Matic seem to have functionality issues.

On the other side, the more popular I Don’t Care About Cookies blocks or hides most cookies, but it will automatically accept cookies that websites need in order to function. This may not be ideal from a privacy perspective, because it doesn’t give users a clear option to go back instead of accepting these necessary cookies.

Another option is to install uBlock Origin and use the Easylist Cookie List, which blocks many of the requests to accept cookies. uBlock can also be configured to block a lot of ads and popups. Given that dark patterns often begin through these vectors, using uBlock can also help you defend yourself against dark patterns.

NoScript blocks scripts from running in your browser, so it can also be good for avoiding dark patterns for similar reasons. However, blocking scripts also breaks a lot of pages, making your web experience a lot clunkier. NoScript is probably best reserved for power users.

The future of dark patterns

While there are some promising legislative steps in important regions like California and Europe, we still have a long way to go before we completely get rid of dark patterns. We may never even get there, but hopefully as awareness grows, we will at least be able to weed out the most egregious practices.

For now, there’s little that an individual user can do, apart from employ the tactics to protect themselves mentioned above, report badly behaving companies, and vote for candidates who are pro-digital rights.

Apart from that, we just have to sit back and wait, while trying not to get too frustrated whenever we get caught in the grips of dark patterns.