Cryptojacking involves using either malware or a browser-based approach to mine cryptocurrency with the computers or devices of others. Unfortunately, it isn’t done benevolently for the most part. The unsuspecting victims don’t end up with wallets full of coins – instead, the cryptocurrency reaped goes straight back to the person who initiated the cryptojacking campaign.

A single hijacked device won’t make an attacker a whole lot of cash, but if they target thousands or millions of computers, tablets, smartphones and IoT devices, it can be a lucrative moneymaker.

Certain instances of cryptojacking can be viewed as legitimate revenue-makers for websites, however, the vast majority of cases involve deceit or worse, and the practice is generally looked at unfavorably.

If you want to conceptualize the process with a more tangible analogy, imagine a gang siphoning off a liter of gas each from thousands of cars. Many drivers would never have a clue, because it’s a relatively small amount. It probably wouldn’t have too much of an impact on their overall finances, either.

However, when the gang pools each of these single liters together, it ends up with thousands of dollars worth of gas, which it could then sell on the black market. By taking just a small amount of resources from many different victims, they can end up making handsome profits while barely being noticed.

There are a couple of differences in how cryptojacking actually plays out, but the analogy should still give you a rough idea of how it works. While cryptojacking may seem relatively benign, the major problems with the practice are that it is often done without consent, and that it can cause performance issues for those affected.

What is cryptojacking?

Cryptojacking has two major components. The first is the relatively benign cryptocurrency mining software. The other component involves finding some way to leverage resources from the computers or devices of targets, with the end goal of sending the mined cryptocurrencies back to the entity behind the campaign, whether it’s a legitimate business or an attacker.

What is cryptocurrency mining?

Mining is one of the core processes involved in the function of cryptocurrencies. It acts as a validation system, where miners (this can be anyone with the necessary software and equipment who wants to participate) compete to solve mathematical puzzles that involve hashes.

This is called the proof-of-work system, which is used by the cryptocurrencies mentioned in this article. An alternative system known as proof-of-stake system is used in Ethereum and other cryptocurrencies, but it’s outside of the scope of this article.

The mathematical puzzles require large amounts of computational power, which means that miners need to pay for equipment and electricity to compete. To incentivize this output, the first miner to solve the puzzle and have their block added to the chain of previous record-keeping blocks (hence blockchain) wins a set amount of cryptocurrency, which they can then hold on to or sell, ideally making a profit that justifies the equipment purchases and ongoing electricity costs.

For Bitcoin, this reward is currently set at 12.5 coins (valued at a little over US$120,000 at the time of writing). However, this amount halves periodically, after reaching certain milestones in the total number of coins already mined.

The mining process serves to confirm that previous transactions have already taken place, creating an unalterable blockchain that anyone can verify. This prevents malicious users from trying to spend bitcoins twice and creates a permanent record of all transactions on a distributed and decentralized ledger. The validation process of mining is essential to the function of the entire ecosystem.

For established cryptocurrencies, mining is generally done on an industrial scale with ASIC and FPGA machines – these are essentially finely tuned computers that are effective at mining cryptocurrency. Since mining is so energy-intensive, it is mainly done in countries with cheap electricity, such as China, Iceland, or Venezuela.

To give you an idea of just how power-hungry mining can be, in 2019 Bitcoin mining was using about as much electricity as the entire country of Switzerland. And that’s just one coin of many.

How do entities mine cryptocurrency on the computers or devices of their targets?

The first step is to acquire cryptojacking software. This is generally just normal cryptomining software that has been altered to run quietly in the background.

When done in a dubious manner, it’s important for cryptojacking to be stealthy. This is because whenever a victim notices unusual activity, it generally prompts them toward a much quicker discovery, then removing the cryptojacking software.

If attackers can run the cryptojacking software secretly on their targets for months or years, their ventures will be far more profitable than if it is discovered and removed within days or weeks.

In some cases, the cryptojacking software is binary-based and the targets need to download and execute it before it will start mining. Alternatively, cryptojacking can also be done at the browser level. This means that simply visiting certain sites can potentially lead to cryptojacking.

If this is the case, the website, its advertisers or attackers could be using your computer’s resources without your knowledge, and all without you having to download a thing. In certain situations, this may not be so bad – your favorite websites could be using a small proportion of your resources to mine cryptocurrency instead of (or in addition to) showing ads.

Torrent sites were some of the earliest adopters, but it spread to a range of others as well, including the publisher Salon. While cryptojacking isn’t intrinsically bad, the approach often cops criticism because it’s generally done without asking for the user’s permission beforehand.

Doing something without a user’s knowledge or consent already crosses an ethical line, but many of these cryptojacking campaigns take things a step further and abuse significant amounts of their victims’ resources. These power-sucking attacks make it difficult for the targets to accomplish tasks on their computers and sometimes cause more serious problems.

The most famous example of browser-based cryptojacking is Coinhive, which blurred the lines between an innovative funding model and a new technique in the cybercriminal’s playbook. We will cover it in more detail in the Cryptojacking popularity & the rapid rise of Coinhive section, where we discuss how cryptojacking went from an unsuccessful concept to a huge threat within a matter of months.

Other forms of cryptojacking malware aren’t too hard to develop since it’s mainly comprised of the regular, completely above-board cryptomining software. More sophisticated attackers will make their own versions, or tweak previous cryptojacking software so that it suits their mode of attack better. This can involve alterations to help slip it past the latest detection and prevention methods, such as antivirus programs or ad blockers.

Those without any technical skills don’t have to miss out. They can acquire cryptojacking malware quite cheaply on darknet marketplaces.

Finding targets (or willing participants)

Once an attacker has their cryptojacking software, the next step is to spread it. There are a few different ways to do this. The classic way is to treat it like any other malware, and either take advantage of security vulnerabilities or manipulate potential targets into downloading it.

Some of the common techniques include:

- Drive-by download attacks that look for old and outdated versions of software that can be exploited to load malware onto victims’ computers.

- Social engineering attacks that involve tricking users into downloading the cryptojacking software under the presumption that it is something else.

- Bundling it with other desired software in the hope that targets don’t notice.

It’s not just PCs that can fall victim to cryptojacking malware. Smartphones, tablets, routers and poorly secured IoT devices can also be infected. A number of apps have also been found to secretly mine cryptocurrency on the unwitting users’ devices.

When browser-based cryptojacking is used legitimately, all site owners have to do is host the code on their websites and notify the users of the practice. The site visitors who consent will then mine for them, creating an extra source of revenue.

Dodgier sites do this in secret, using their site visitors’ resources without informed consent. Legitimate sites may also be compromised by attackers and have cryptojacking scripts added. This can lead to the site visitors mining cryptocurrency for the attackers, all without the site owner even knowing.

Regardless of whether a cryptojacking campaign is malware or browser-based, consensual or part of an attack, the end goal is essentially the same. The infected systems or the site visitor’s browsers form a pool of their collective resources and work toward solving cryptographic puzzles that yield rewards.

Why do attackers cryptojack?

Cryptocurrencies have real-world value, however unstable they may be. While they haven’t become the mainstream payment method that many were predicting, it’s hard to deny that they have found at least some long-term uses.

Aside from speculation and a lot of blockchain-based business ideas that have yielded little, their decentralized nature has made them useful for making purchases in illicit marketplaces and for money laundering.

There are two ways that one can acquire cryptocurrency. The first is by trading fiat currency – such as the US dollar or the Yen – for bitcoins or one of its many rivals, via a cryptocurrency exchange. The second method is to mine them. In the past, this could be done with the spare processing power on a PC, but it now requires exceptional amounts of computational power and is generally done with special equipment.

This approach is expensive, both in terms of the electricity it uses, and the amount of equipment it requires. A lot of people want to make money through cryptomining, but either don’t have the finances to get started or simply don’t want to pay. However, with a little ingenuity and a skewed moral compass, there is another way – cryptojacking.

If someone is willing to cryptojack, it gives them a way to mine cryptocurrencies without having to use their own computational resources or pay for the machines. If they manage to take over enough devices, they can have a large amount of processing power at their disposal. It can be a very lucrative business – mining thousands or millions in cryptocurrencies, often without the targets ever knowing.

Essentially, cryptojacking transfers the costs of mining cryptocurrency from the attacker to the targets. But if cryptojacking only takes up spare computational power, does that make it a victimless crime?

What are the negative effects of cryptojacking?

The two major issues surrounding cryptojacking are that it is often done without consent and that it can negatively affect its targets.

Cryptojacking without consent

One could compare cryptojacking to guerrilla gardening in urban landscapes. Just as the proponents of guerrilla gardening advocate using someone else’s vacant land to grow vegetables, why not use someone else’s unused PC power to mine cryptocurrency? No one gets hurt, right?

While it seems like cryptojacking is just a way of maximizing efficiency by taking advantage of otherwise unused resources, in reality, it often ends up being more harmful and can have negative effects.

One of the primary issues is that it is often done without the knowledge or consent of those who are affected. If a user consents to cryptojacking, with full knowledge of what it means and what will be happening on their computer, then it’s pretty hard to find any objections to the practice. It actually opens up a new and legitimate opportunity for websites to raise revenue.

However, in reality, most users never even know that it is happening, let alone have an opportunity to consent. But is consent really that important in cases where cryptojacking causes no noticeable harm?

Let’s consider another analogy. What if you had left the lights on in your home before going out, and someone found a way inside so that they could take advantage of the light to read a book. Even if they didn’t break anything and had slipped out before you came home, causing no inconvenience, you would still feel violated if you ever found out.

If we tweak the above situation a little bit, many people would be completely fine with it as long as the renegade reader asked beforehand. After all, they wouldn’t be causing any harm or costing the home occupant anything. At the end of the day, it’s your computer or device, and you should have control over what processes occur on it.

The negative effects of cryptojacking

The above analogies don’t totally encapsulate the issues with cryptojacking, because it actually comes with costs to those who are affected. People may not mind if cryptojacking only gave up their excess processing power when their systems aren’t in use, but in reality, cryptojacking uses more electricity, slows down other tasks that a user may be trying to accomplish, and can cause wear on the equipment.

Whenever a computer or phone is used more intensely, it uses up more electricity. You would have noticed this all the time – if you leave your phone in your bag on airplane mode all day, you’re probably surprised by how much battery it has left, especially compared to those times when you spend all day doing power-hungry activities like browsing or watching YouTube.

Cryptomining can be incredibly intensive, so it can drain your battery much more rapidly than normal and draw a greater amount of electricity from your home. The actual amount of power consumption depends on how many devices in your home are involved in cryptojacking, how intensely they are mining, and how long they are on for.

In more moderate cases, you may not notice a major difference in your home’s total power consumption, but the act of cryptomining certainly does use additional power.

Websites and attackers that engage in cryptojacking will often try to make as much money as they can out of your computational resources, so they may end up hijacking such a large volume of processing power that it slows down your other activities and tasks.

While the amount of resources drawn will vary, cryptojacking malware or browser-based cryptojacking can cause other websites to load slowly and make many processes lag. When an Ars Technica reporter visited a website that hosted a cryptojacking script, they saw a huge spike in their CPU load. When they closed the site, it dropped back down from a whopping 95 percent to just nine percent.

If you were to have multiple tabs in your browser that were all cryptojacking, it could leave your computer essentially unusable. All of this activity can also heat up your device. This puts additional wear on components such as your fan, and can lead to breakages as well as shorter lifespans.

Cryptojacking popularity & the rapid rise of Coinhive

All this talk about the dangers of cryptojacking may come across as another ever-growing online menace that you now have to be terrified of. But we have good news – incidences of cryptojacking have declined steeply in the last year or two.

While it’s much less of a threat than it was previously, there’s always the chance that this is just a momentary downturn and it could be back with a vengeance if various market forces change. To explain why we’ll take you back to the early days.

Cryptojacking has its roots in 2011 when Bitcoin was still in its infancy and mainly used by cypherpunks and on illicit online marketplaces. In May, a service called Bitcoin Plus was launched, and it allowed websites to embed a script on their pages that mined bitcoins for them, using the resources of their site visitors.

Perhaps ahead of its time, Bitcoin Plus did not take the world by storm. At the time, the price of a bitcoin ranged between about $5 and $30, compared to the almost $20,000 it reached at its peak. It wasn’t really profitable due to the low coin values, so the concept didn’t see any widespread adoption.

In 2013, a similar project called Tidbit emerged. It was developed by a group of MIT students but was stymied by legal problems because the script did not obtain consent before using site visitors’ computers for mining. In the end, the developers were left with a $25,000 suspended monetary settlement hanging over their heads.

The New Jersey Division of Consumer Affairs prohibited the group from accessing computers of New Jerseyans’ without explicit consent – otherwise they would have to pay the fine. This order seems to have put a stop to Tidbit’s cryptojacking venture.

As the price of Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies began to rise, ASIC miners moved onto the scene. These are essentially computers that are set up to maximize their cryptocurrency mining abilities, which made it more difficult for cryptojacking malware on PCs, or browser-level cryptojacking services to compete.

Enter Coinhive

This all started to change toward the end of 2017, when the cryptocurrency market was reaching its peak. In September, a new service called Coinhive was launched. Much like Bitcoin Plus and Tidbit, it made it simple for websites to mine cryptocurrencies through their site visitors’ browsers.

One of the main differences between Coinhive and its predecessors is that it mines a privacy-centric coin called Monero rather than Bitcoin. With the launch of Coinhive and the high price of Monero, we saw a huge spike in browser-based cryptojacking in late 2017.

Coinhive made it much easier for websites to integrate browser-based cryptojacking. While the company recommended that websites let their visitors know when their browsers were being used to mine cryptocurrencies, the reality is that many didn’t notify them or ask for consent.

Initially, Coinhive made no attempt to enforce its adopters to notify their site visitors. Not only did this lead to a large number of websites using it secretly, but cyber criminals also integrated Coinhive into their attacks.

It was relatively simple to hack vulnerable sites and insert the Coinhive script onto them, with any Monero mined by the site’s visitors going straight to the wallets of the attackers. Many site owners didn’t have a clue that their website was cryptojacking visitors.

With the price of Monero peaking, Coinhive scripts were found everywhere, including:

- Browser extensions.

- YouTube ads.

- Ad networks.

- Mobile and desktop apps.

- Chatbots.

- Major websites – both government and commercial.

According to security researcher Troy Mursch, both the legitimate, non-consensual and criminal uses of Coinhive led to the company holding 62 percent of the browser-based cryptojacking market share, as of August 2018.

An article by security reporter Brian Krebs illustrates how Coinhive wasn’t doing much to stop the rapid rise of its use by hackers – after all, the company received 30 percent of the mined Monero whenever their script was used by a site, regardless of whether it was the owner or a hacker who put it there.

Krebs highlighted the fact that Coinhive generally didn’t respond to complaints from site visitors who were having their resources hijacked on hacked websites. In cases where it did respond to these complaints, it would invalidate the wallet’s key attached to the cryptojacking endeavor.

What would this do? It didn’t stop the mining. All it did was stop the hackers from receiving their 70 percent. This meant that Coinhive would receive 100 percent instead, essentially tripling its profits. Coinhive stated that this was due to technical issues, and that the company was working on a fix. Given the financial incentives, it’s easy to question just how motivated the company was to change the practice.

To be fair to Coinhive, it did eventually release another version of its script known as AuthedMine, which asked for consent from site visitors. Unsurprisingly, it never took off, with Krebs reporting in March 2018 that 32,000 websites ran the original Coinhive script, but under 1,200 bothered with AuthedMine.

Coinhive blamed the limited success on antivirus software that blocked both the original script and AuthedMine, stating, “Why would anyone use AuthedMine if it’s blocked just as our original implementation?”

The company did kind of have a point. It’s not profitable for a site owner to embed a cryptojacking script that will be blocked by many of its visitors. This left little incentive for websites to use the new version, which left behind cyber criminals as the main cryptojackers – they sure weren’t going to switch to a version that asked for consent and diminished their profits.

The tide begins to turn

In a more general sense, once various cryptojacking scripts became popular, antivirus programs and adblockers began to block them. This meant that a smaller portion of site visitors would lend their resources to cryptojacking scripts, decreasing the pool of targets that either site owners or cybercriminals could make money from.

At around the same time, the value of Monero and other cryptocurrencies began to plummet. From its peak of almost $500 in January of 2018, Monero was worth just one-tenth a year later. This also made cryptojacking the currency far less profitable.

When you add in a bunch of copycat services that were copying Coinhive’s shtick, the competition and the market factors made the business untenable. Coinhive announced that it would be closing, eventually closing shop in March 2019.

Similar factors impacted the industry as a whole, and we began to see instances of cryptojacking drop significantly. It simply stopped being lucrative for both site owners and criminals. The authorities also began to catch on, and various operations began to crack down on illegal cryptojacking enterprises.

A report from the cybersecurity firm SonicWall helps illustrate just how precipitous the drop was. At the start of 2019, they were still registering eight million cryptojacking signature hits per month. By December, the number was down to about a quarter of a million.

While cryptojacking is currently much less of a threat than it was in 2018, it is possible that various factors could lead to its resurgence. You may not have to worry about it too much now, but a spike in cryptocurrency prices could lead to its second coming.

Other examples of cryptojacking

As dominant as Coinhive was, it was far from the only cryptojacking threat:

The Kobe Bryant wallpaper

While many people were mourning the tragic death of the basketball star, cybercriminals were taking advantage of it. They used steganography to hide malicious code inside a Kobe Bryant wallpaper that was being shared around.

The malicious HTML file was a Trojan that led victims to a website that hosted a cryptojacking script. When victims went to the site, the Coinhive-based script would run, using their processing power to mine Monero for the attackers.

In response, the Windows Defender SmartScreen tool was altered to block the website. This prevented those with the latest versions of Windows 10 from accessing the site, which stopped the attack from working against those who installed the update.

The MyKings botnet

The Kobe Bryant wallpaper scheme and the MyKingz botnet had something a little unusual in common – they both used celebrity images to spread their attacks at some stage. Despite this, many of the other elements in the attacks were quite different.

MyKingz is a cryptojacking botnet first discovered in 2017. Various cybersecurity firms call it DarkCloud, Hexmen or Smominru, but it’s all the same botnet under different names. Throughout its history, it used various tactics to spread and infect new devices. These devices would then be used to mine cryptocurrencies with a range of different scripts.

It spread rapidly by scanning for a wide variety of vulnerabilities, including MySQL, MS-SQL, Telnet, SSH, RDP and more. Whenever MyKingz found openings, it pounced and infected the systems.

It was also known to use the EternalBlue exploit at times, although this was just one component in its versatile arsenal that helped it grow to infect over half a million Windows systems within a few months. In September 2019, MyKingz was still causing almost five thousand infections each day.

One of the latest developments from the group behind MyKingz was to use steganography to hide a malicious script inside a picture of Taylor Swift. This helped it to slip past enterprise networks, which would just see a seemingly harmless JPEG, rather than the dangerous EXE.

They used the image as a foothold to install their cryptojacking malware, mining with the victim’s resources and then sending the currency back to the group that commands the attack.

Other versions of the attack didn’t stop at cryptojacking. They would also introduce a remote access Trojan (RAT) and a data harvesting module. This secondary component allowed the theft of credentials and other sensitive information. It’s possible that this innovation was driven by the shrinking profitability of cryptojacking – the attackers may have started looking for other opportunities to make money once it stopped being so lucrative.

The discovery of Vivin

Vivin is a threat actor that was discovered by Cisco’s Talos in late 2019, but it is thought to have been active since at least 2017. Vivin initially spread its malware by disguising it as pirated software, such as games or tools.

The malware was spread through forums and other sites. Many of its iterations included self-extracting RAR files that appear to be installing the real file, while secretly installing the malware. The execution chain involved a number of steps, including contacting a malicious domain, which Talos presumed to act as a command and control center.

It used obfuscated PowerShell commands, eventually leading to the execution of a Monero cryptomining payload. The miner was set to use 80 percent of the target’s CPU resources, which has a significant effect on the usability of the affected systems.

Vivin would switch up its tactics from time to time, altering its delivery chain and obfuscation methods, as well as the wallets that it used for the mined cryptocurrency. Despite these moves, Talos described the threat actor as having “poor operational security”, leaving behind many mistakes that allowed the researchers to connect the dots and build up a profile on it.

Cryptojacking apps found in the Microsoft Store

In 2019, Symantec discovered eight separate apps available in the Microsoft Store that would secretly mine cryptocurrency with the resources of whoever downloaded them. The apps supposedly came from three different developers, although Symantec suspects that the same individual or organization was behind them all.

The apps included browsers, battery-saving tutorials and video apps. Potential targets could encounter the cryptojacking apps through keyword searches within the Microsoft Store, as well as on lists of the top free apps.

When someone downloaded and launched one of the apps, a Google Tag Manager in the domain services would fetch some cryptojacking JavaScript code. The miner would activate and start digging for Monero, using up a significant amount of the device’s resources, slowing it down considerably.

The apps were published throughout 2018, but Microsoft removed them from its app store after it was contacted by Symantec. It’s not known exactly how many people were affected by cryptojacking apps, but the researchers suspect that it was a significant number.

Tesla cryptojacking

One of the most high-profile victims of cryptojacking was the electric car company, Tesla. In 2018, a cybersecurity firm called RedLock posted a report that detailed how cybercriminals had infiltrated Tesla’s AWS cloud infrastructure and used it to mine cryptocurrency.

RedLock came across the scheme during one of its scans for insecure and misconfigured cloud servers. They discovered an open server that was running a Kubernetes console, which is used as an administrative portal in cloud application management.

The Kubernetes console turned out to be mining cryptocurrency, and as the researchers dug deeper, they discovered that it was Tesla’s. It appears that the attackers had come across this Kubernetes console, and realized that there was a huge security lapse – it hadn’t been password protected. Anyone could access it, so of course the hackers did.

Inside was a storage container that held credentials for the Tesla AWS infrastructure. With the login details in hand, the attackers set up their cryptojacking scheme, which was based on the Stratum Bitcoin mining protocol.

RedLock couldn’t say just how many bitcoins the operation may have mined, but there was the potential for it to be substantial. Large organizations like Tesla already use significant amounts of electricity and processing power, so a hefty cryptojacking scheme may be able to continue without any noticeable usage spikes, keeping it undetected.

Once the attack was revealed, Tesla addressed the issues within a day, putting a stop to the cryptojacking venture that was taking advantage of its resources.

The Outlaw botnet

In 2018, Trend Micro discovered a hacking group that it dubbed Outlaw. A host part of its botnet was found attempting to run a script in one of Trend Micro’s IoT honeypots. The bot used a tool named haiduc to find systems that it could attack by taking advantage of a command injection vulnerability.

When it succeeded, it tried to run a cryptojacking script. The script checked for other miners on the system, and if it discovered any, it stopped them from running, then ran its own binaries. Not only could it mine a larger amount of currency if it wasn’t sharing a system’s resources with one or more other cryptominers, but Outlaw’s process allowed it to take over mining activities from other botnets.

Once it had put a stop to any other miners, the bot checked whether its own Monero miner was operating. If not, it downloaded the files again and restarted the process, once more checking for other miners. This design meant that Outlaw could expand its reach significantly by taking over from competitors.

By the end of 2018, Outlaw had already achieved significant success, with more than 180,000 compromised hosts, including Windows servers, websites, IoT systems and Android devices.

Cryptojacking for good

Much of this article has been pretty negative, because cryptojacking is mostly done without permission and has consequences for the victims – all to satisfy the instigator’s greed. Despite this, we do have some good news, so you don’t have to give up your hope for humanity just yet.

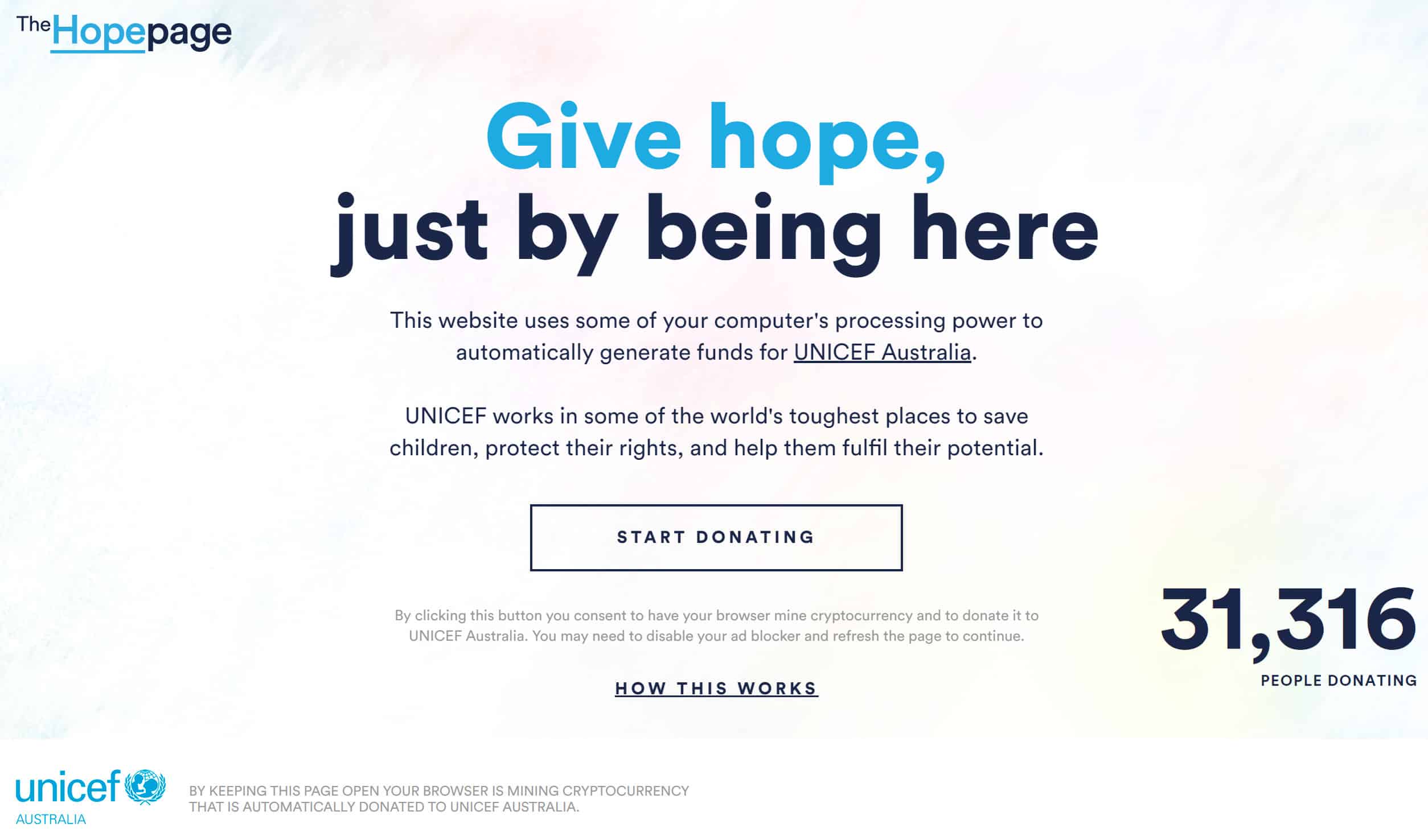

In 2018, UNICEF Australia launched the Hopepage as an innovative way to raise funds. By going to the website and clicking on the Start Donating button, you could use your computer to help a good cause.

At the time of writing, the website doesn’t seem to actually be mining, and it’s not known whether this is just a temporary issue. UNICEF Australia hasn’t made any announcements regarding its current status. If it does resume and you would like to contribute, those of you that run adblockers or scriptblockers may need to disable them or add an exception for the site.

You could use your computer to mine and help out a good cause, all just by leaving the page open in your browser. The longer it runs, the more you contribute. The page used the computing power of its visitors to mine cryptocurrency, which was then automatically donated to UNICEF Australia and converted to real money. The organization then used the funds as part of its charitable endeavors.

One of the good things about the page was that it allowed site visitors to choose how much of their processing power they were donating. If it slowed down their computer too much, they could cut it back to a more manageable level. Alternatively, they could just let it run whenever their computer was idling.

The Hopepage originally used Coinhive’s AuthedMine script, the one that actually asked for consent. However, after Coinhive shut down, UNICEF Australia may have switched to an alternative, or the site has just been sitting in purgatory since then.

You don’t have to worry about ventures like the Hopepage, because they aren’t like all of the other cryptojacking schemes that we mentioned. Not only is the Hopepage for a good cause, but it clearly asks for consent, and you can easily control when and how much of your resources it uses. All you have to do is close the page when you want it to stop.

How to detect cryptojacking

If this article has filled you with fear of a new threat, you may be wondering, “What if I’m being cryptojacked right now?” One of the major signs is if your computer or device had suddenly become much slower for no apparent reason.

In more extreme cases, you may notice the fan kicking in or the device overheating. However, there can be a bunch of other causes for this, such as different types of malware, so the diagnosis isn’t so straightforward.

Unless you have a house packed with devices that are actively cryptojacking, you might not notice a spike in your electricity bill, but it’s still possible. Another option for cryptojacking detection is to run an antivirus scan and see if anything pops up. Although some legitimate cryptojacking code may be whitelisted by certain antivirus software, the more common ones that cryptojack in secret are likely to be flagged.

When it comes to apps, Apple is pretty good at keeping cryptojacking out of its stores, and the Play Store tries to stay on top of the threat as well. If you do suspect that one of your apps is cryptojacking, the best way to detect it is to go into your settings and check your mobile or wifi data usage. If you notice any apps using an excessive amount of data, there is a chance that it is cryptojacking (or sending off an excessive amount of your personal data).

If you think that a website might be cryptojacking through your browser, it’s easy to check it with Cryptojacking Test. This tool was developed by Opera, and all you have to do is visit the site and click the Start button. The test will then check whether any of the other sites open in your browser are currently cryptojacking.

Obviously, you will need to have any suspected pages open while you run the test. If the test comes back affirmative and a website is cryptojacking your resources, all you have to do is close the site to make it stop.

How can you remove cryptojacking malware?

If you have inadvertently downloaded cryptojacking malware, it’s important to get it off your computer or device so that it can return to its normal state. If your antivirus picked it up the malware, it should be easy to follow the prompts and either quarantine it or remove it completely.

If you are sure that you have cryptojacking malware, but your antivirus hasn’t been able to find it, you can also try to restore your computer to a previous point, or completely reformat your hard drive.

If you suspect that one of your mobile apps is cryptojacking, all you have to do is delete the app. If it truly was cryptojacking your resources, you should notice that your battery lasts longer and the speed returns to normal.

How can you prevent cryptojacking?

Cryptojacking prevention methods vary according to whether it’s browser-based or malware-based, however, they generally align with many security best practices. To stop cryptojacking in your browser, it’s a good idea to use an adblocker like uBlock Origin. You can also use a script blocker like NoScript, or just disable JavaScript in your browser.

Alternatively, you can just stick to reputable websites. Most of these won’t use cryptojacking as a funding model, and if they do, they are likely to notify you and ask for consent beforehand – the negative publicity that comes from secretly using cryptojacking just isn’t worth it for most reputable sites.

Of course, there is still the possibility for attackers to compromise the site and insert cryptojacking scripts. While reputable sites tend to have better security, their vulnerabilities can still be taken advantage of occasionally. Due to this threat, using adblockers and automatically blocking scripts from running is a more universally secure option.

As for cryptojacking malware, you can avoid it in essentially the same way you avoid other malware. Important practices include:

- Staying away from dodgy websites.

- Keeping your software updated.

- Educating yourself on social engineering so that you can recognize and avoid phishing attacks.

- Not pirating files.

- Only downloading software from the original source. Watch out for bundles, because sometimes cryptojacking files could be included in the package.

- Using a good antivirus.

- Only download trusted apps from the App Store or the Play Store.

What if your website has been compromised with cryptojacking code?

If you run a website, it’s possible for hackers to infiltrate it and insert cryptojacking code. You may notice your site loading slowly, or receive notifications from your security tools or site visitors. You can also confirm whether cryptojacking is taking place by running Cryptojacking Test while your site is open in another tab.

If this is the case, it’s a very serious issue – not only has your site been draining the resources of its guests, but it also means that your site has been compromised and attackers could be causing other damage.

You can try to find the cryptojacking code by opening your website in a browser, right-clicking on the page, then clicking View Source. Scan the page looking for any unusual domains or file names, especially anything related to coins, mining or cryptocurrency.

You should also try scanning for malware through your website’s dashboard. If you find the code, remove it. While you’re at it, search for any other changes the attackers may have made and reverse any that you find. You will also need to harden your security. This includes the basics like changing your passwords, updating all of your software and setting up two-factor authentication.

To prevent your site from being used for cryptojacking in the future, you should also set up regular file integrity monitoring, create a content security policy (CSP) and only include JavaScript from trusted sources.

Can cryptojacking be legitimate?

While much of this article has taken a negative tone toward cryptojacking, the technique itself isn’t inherently bad. If websites ask for explicit consent before conducting it at the browser level – or give their users the opportunity to choose between it and ad displays – the process doesn’t have to be wholly negative.

If websites want to pursue this strategy, then they should also adopt authentication protections to restrict cybercriminal activity, and also put caps on just how much of a user’s resources they draw. If they get too greedy, it makes the user’s experience noticeably slower and can have other negative impacts.

Not only could caps reduce the negative effects, but in turn, they would also reduce the animosity that many people have toward cryptojacking. This could lead to users whitelisting the activity on their adblockers, allowing websites to cryptojack from a larger pool of users.

As we saw above in our UNICEF Australia example, cryptojacking can be used for good, and if it is done following the appropriate guidelines, it has the potential to be a viable and legitimate funding model. However, it may not always make financial sense, especially when the values of various cryptocurrencies are low.