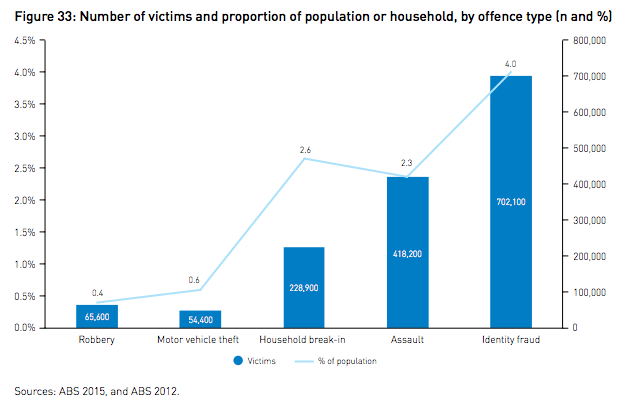

Credit card fraud is big business. The United States accounted for almost half (47%) of the world’s credit card fraud in 2015 probably due to the slow adoption of Chip and PIN cards in the U.S. This type of fraud in the U.K. reached £567 million in 2015 and Canada landed somewhere in the middle at almost $1 billion dollars in 2015. In Australia, credit card theft is considered a type of identity fraud which affected four percent of the population in 2013.

Identity crime and misuse in Australia 2013-14 https://aic.gov.au/publications/rpp/rpp130

The stage was carefully set to enable these massive levels of fraud over the past several decades. When credit cards were first issued they were annoying to use. Store clerks had to manually refer to printed books or make time-consuming phone calls to verify each credit card sale, which did little to impress card holders. More problems arose with liability. Card holders weren’t keen on carrying around a card that, if lost or stolen, could leave them on the hook for thousands of dollars of fraudulent charges. In order to drive credit card adoption, the issuers had to make credit cards as easy as possible to use and remove liability.

So, they did.

Those efforts to drive credit card adoption at all costs have created a world where the card owner is not usually held responsible for fraudulent charges, so there is little impetus to obsessively safeguard credit cards. On the other hand, the card issuers now make billions in profit each year. Even though they sustain what seems like staggering losses due to fraud, it’s frequently less trouble to just write it off and move on. This creates a situation where few but the largest fraudsters are ever pursued, seeding fertile ground for a huge number of low-level criminals.

- Why do they do it?

- How is it done?

- What is the industry doing to address this problem?

- How can I protect myself?

- What do I do if my card has been stolen?

Why do they do it?

It’s tempting to think that you’re just up against a guy who wants to steal your card to put some gas in his car, but the reality is much different. The guy trying to steal your credit card is most likely just the point man for a much larger criminal organization. The internet is rife with carding

sites where buyers and sellers can exchange packs of stolen credit cards and those transactions start with individual credit cards like yours. Many of these sites exist on darkweb marketplaces such as Tor hidden services, but there are many so-called “carding” sites on the regular internet as well.

At a minimum, the thief is going to need your credit card number, expiry date and CVV (Card Verification Value) number. Those are the minimal three requirements to use a credit card. However, there are ways thieves can up the resale value of your credit card data.

In order to get the best price for his batch of credit cards, a thief will run all the stolen credit cards through ‘checker’ systems that verify if the card is still active. These systems make what seem like small, innocuous purchases that don’t eat too much out of its remaining credit limit, but also confirm that the card has not been cancelled.

Taking it one step further, packages of full personal data is worth more than just a working credit card number. If a thief is able to steal detailed personal information about you in order to allow the buyer to steal your identity, it’s worth even more. The most valuable batches of credit card data usually include enough information for the buyer to completely assume the identities of the rightful owners, or at least enough information to do things like redirect the owner’s mail as the first step in stealing their identity.

It’s worth noting that there is a significant difference in how fraudulent charges are handled when a credit card is used versus when a bank debit card is used. In the latter case, the customer is usually liable for any fraudulent activity and has little or no recourse to recoup their money since it is already spent when the transaction occurs. Credit cards, on the other hand, have the credit card company as an intermediary so the credit card company tends to be liable for the fraudulent activity. The laws in your country and the practices of your bank may vary.

How is it done?

As with any operation, methods that provide the highest rate of return are preferred. In order of importance, the main criteria that determines the value of stolen credit card data is:

- validity: cards must not be cancelled and have some clearance

- volume: a single credit card is not worth that much. The more the merrier

- credit limit: higher-value cards are worth more. Card data stolen from places where higher-income people congregate are likely worth more

The preferred theft methods will focus on the best combination of these three criteria. Some of the more common methods of stealing credit cards follows.

Website data breaches

Successful data breaches on websites start with volume. Poorly secured websites can allow thousands, perhaps tens of thousands of credit cards to be stolen at a time. From there, the other two criteria can be established: how many are valid and how many belong to high-worth owners.

Website breaches from high-profile websites are typically harder than stealing from one-off, smaller vendor sites, but most website breaches have one thing in common. It can take time for the website to know it has been breached if it ever finds out at all. If the website owners do discover the sites has been breached, there is typically a delay while the scope of the breach is discovered and notifications sent out to the affected customers. When all those delays are put together, website breaches are attractive because they can afford the thief a long lead time to sell the cards before they’re even known to have been stolen.

Card Skimming

Credit card skimming is not the same as the old skimming the cash drawer

technique. This type of skimming refers to affixing some kind of mechanical device over a legitimate card reader to record the credit card data. In countries with Chip and PIN

technology, a camera is also usually set up to record the PIN entry.

Aaron Poffenberger,

Aaron Poffenberger,

https://www.flickr.com/photos/27047834@N02/5562783372

Once a card is skimmed

there are a few ways it can be used. Enough information has already been collected so that the card can be used online or in other non-PIN situations. If the PIN is also collected, then the cards can be cloned

and legitimate looking credit cards programmed with working credit card data can be created and sold.

Thieves that use skimmers usually remove their devices after a short period of time. If the skimmer is discovered, then it is usually possible to determine a time frame of when it was deployed. From there, the credit card company can cancel and replace the cards that were used at that site during that time frame. This would make the entire batch of cards worthless.

Skimmers are usually deployed on machines in areas with little human oversight. Gas pumps, isolated vending machines, and car washes are ripe targets for skimmers. Highly attractive areas known to be monitored with cameras or security personnel such as bank machines are less likely to be used for skimming operations.

Manually copying cc info

The goal of manually copying credit card data is the same as skimming, but there is no machine involved. The best environment for manual copying are places where you expect your credit card to be taken from your view for a short period of time such as when paying the bill in a restaurant. In those few moments, the server can copy your credit card number, expiry, and CVV before returning the card back to you.

Manual copying does not work very well in countries that have wide deployment of Chip and PIN cards because the server would not have ready access to your PIN at the time of copying. The best case scenario is to try to watch the customer enter their PIN and record it after the fact.

Telephone and Email scams

Sometimes, lower-tech scams can work, especially against people who do not tend to use the internet as much. A typical telephone scam will have the same hallmarks as an email scam. The scammer will paint a picture that some bad thing is about to happen unless you pay some amount of money immediately, using your credit card, of course.

Most scams will work over either phone or email and can include promises of things such as:

- Inexpensive vacations that require immediate payment to secure your spot

- A charity pulling at your heart strings to stop some terrible atrocity

- Offers to purchase normally unavailable medicines or medicines at a deeply discounted rate

- Legal or arrest threats from government agencies

Telephone scams will attempt to get your credit card information on the call. Email phishing scams are a little more in-depth in that they will contain a link to a realistic looking payment page in the hopes you’ll go there and enter your sensitive credit card information.

What is the industry doing to address this problem?

The biggest advancement in card security to date is EMV, or Chip and PIN

.

Originally, merchants only needed to capture the customer’s signature in order to process the sale. This laughable measure of security existed for many decades and still exists in some countries today. Modern payment processors issue cards with encrypted chips in them and can require the card owner to enter a PIN to make a purchase. The integrated chip on the card generates one-time codes for each transaction. Even if the chip contents were able to be copied, the copied transaction code the chip generated would not be valid for successive sales.

These types of credit cards are called EMV cards which refers to Europay, Mastercard and Visa; the three founding partners of the standard. Colloquially, these cards are known as Chip and PIN cards, although Chip and Signature cards exist for areas with less technology. EMV cards still currently have a magnetic strip on the back as pre-EMV cards did for backwards compatibility. There are machines that cannot process EMV and machines sometimes break down, so the magnetic strip will probably be around for some time to come.

Vendors that have fully implemented EMV cards will only be able to process credit card sales after the customer has entered their PIN. In those cases EMV cards are inherently protected against historical theft methods such as being stolen from the postal mail. Even initial PINs sent with new cards are sent in a different mailing, thus requiring a thief to maintain control over a victim’s postal mail for several days. However, not all vendors have fully implemented the “PIN” part of “Chip and PIN”. Most notably, the United States still does not have widespread adoption of PIN entry for EMV cards and still uses signatures for most transactions.

The EMV chip, coupled with the proliferation of wireless payment terminals in restaurants, has also reduced the number of instances where the card leaves the sight of the card owner, which helps reduce the opportunity for manual copying.

EMV cards are also resistant to mechanical skimming. The credit card data is encoded on the magnetic strip and can be copied by a skimmer, but the encrypted chip data cannot be copied. This increases the complexity of a skimming attack because the attacker not only has to affix an inconspicuous skimmer, they also have to deploy a camera or some other method to trap the PIN. Each additional piece of equipment heightens the risk of detection.

Having said that, there is a huge market for Card Not Present (CNP) transactions. These are credit card transactions of any type where the card is not at the point of sale. Internet and telephone sales are the most common examples of CNP transactions. Because the card is not present, there is no possible way to input a PIN so the transaction is processed using just the card number, the expiry date, and the CVV. Some vendors that process CNP sales try to lessen the risk by collecting additional information such as a shipping address, which they then match to the billing address of the card. Some card issuers have created Verified

programs in which a card holder must complete a separate step online by going to the card issuers site. But these programs are as clunky as the original credit card verification methods of yesteryear and have not gained much traction. This means that EMV cards can still be used virtually unfettered online.

How can I protect myself?

Most of us probably do not spend much time worrying about our credit card being stolen. As of October 2015, if credit card fraud occurs in the U.S., the party that is the least EMV compliant will be liable for the loss and that party would never be the card holder. A card issuer would have to prove negligence or complicity in order to transfer the liability to a card holder, which is very difficult to do. Therefore, it may seem like the worst outcome is having to go a few days without a credit card while it is replaced. In reality, your credit card data can be more valuable as a foothold into your life as an initial step to stealing your identity.

The first step is to try to prevent the theft in the first place. When using your credit card on the internet, ensure you only enter it over an HTTPS encrypted connection in your web browser. While not all HTTPS connections vouch for the trustworthiness of the site, it will at least protect your data from being stolen in transit over the internet enroute to the web site. Off the internet, keep a vigilant eye out for skimmers. When inserting your card into any machine, look at it to see if it looks odd. While none of us know exactly what every credit card machine on the planet looks like, there can be some tell-tale signs that a machine has been tampered with. Card slots with ill-fitting frames, loose tape, and sloppily made instruction plates are all signs of potential skimming.

Aaron Poffenberger, https://www.flickr.com/photos/dabdiputs/5713351185

Aaron Poffenberger, https://www.flickr.com/photos/dabdiputs/5713351185

Even if your card information has been skimmed unbeknownst to you, there are still steps you can take to protect yourself.

The most effective methods of gathering large numbers of credit cards do not telegraph that your card has been stolen. Website breaches and mechanical skimmers stealthily steal your credit card information and you likely will not know it has even happened. However, the thief will want to validate your card to increase its value on the resale market. That is typically done by putting a small charge on your card which is a warning sign. If you see a small charge you don’t recognize, that could be a validation hit. In that case, you will want to contact your credit card company and report it.

It can be time consuming to continually check your credit card balance and transactions. Some credit card companies offer the ability to set up transaction alerts. There is no standard to the types of alerts a credit card company can offer, but if you’re able to set up transaction notifications, that can give you advance warning of a problem. Remember that validation charges are usually small, so set your alerts to trigger on all transactions instead of just higher value transactions. Some credit card issuers are starting to offer two-factor authentication on all transactions. This means that after your transaction is completed at the terminal, you will receive a text message to confirm the transaction is valid before it is posted to your account. This can help combat CNP fraud where a PIN is not a feasible security measure and you should enable it if your card offers it.

Lastly, be aware that no legitimate bank or government authority will phone you and ask for your credit card information over the phone. Be extremely wary of providing that type of information over the phone and only do so when you are 100 percent sure of the identity of the person you are speaking with. A good tactic is to ask for a number to call the person back. A scammer will typically be unwilling to provide such a number in which case you can be almost certain this is a scam. If they do provide a number, hang up and search for that phone number using an internet search engine like Google. You will likely be able to find out very quickly if that number belongs to the organization the person purported to be from, and may also find out that the number has been used in scams previously. If you’re unable to find any information on the number at all, that is a red flag that it is a scam.

What do I do if my card has been stolen?

Report any suspected or actual credit card fraud to the card issuer as soon as possible. They will usually cancel your card immediately and replace it. This will prevent any further fraudulent charges. In most cases, the credit card issuer will also reverse the fraudulent charges after an investigation.

The next step is to contact the applicable credit bureau or bureaus in your country to report your card stolen. While the credit bureaus can’t do much to replace your card or refund fraudulent purchases, they can place a fraud alert on your file. This may help if there is further identity fraud perpetrated against you stemming from the credit card theft.

Once you’ve taken care of the immediate issue, report the fraud to your respective country’s authorities. This can help authenticate the theft and your credit card issuer may require a police report as part of their investigation.

In all countries, report the credit card fraud to your local police force. Credit card theft and fraud are crimes and your local police force will take a report and any applicable future actions.

In the United Kingdom, Action Fraud will also take your fraud report, but it is not clear what they do with this information. You may wish to report it to your local police as well.