A database of more than 115,000 Argentinians who applied for COVID-19 circulation permits was exposed on the web without a password or any other authentication required to access it. The data included names, DNI numbers, tax ID numbers, and other information about applicants.

Essential workers in Argentina can apply for these permits to be exempt from certain COVID-19 quarantine restrictions. Based on the evidence at hand, we believe the data belongs to the San Juan, Argentina government and the country’s Ministry of Public Health.

Comparitech lead security researcher Bob Diachenko discovered the unprotected database on July 25 and immediately alerted the Ministry.

We have not received a response from government officials as of time of writing, but will update this article if we hear back.

Timeline of the exposure

The database was exposed for at least two weeks. Here’s what we know happened:

- July 12, 2020: The database was indexed by search engine BinaryEdge.

- July 25, 2020: Diachenko discovered the database and alerted the Ministry of Health.

- July 28, 2020: The database was taken down, but then inexplicably came back online. Diachenko sent another alert, this time to Argentina’s National Cybersecurity Directorate, who acknowledged the incident and passed on our disclosure to those responsible.

- July 29, 2020: The database was taken down.

We do not know whether any unauthorized parties accessed the database while it was exposed, but given that our research shows unprotected databases start receiving attacks within a few hours of exposure, it seems likely.

By the time Diachenko found it, the database had already been infiltrated by a “meow bot”, an automated bot responsible for destroying hundreds of exposed databases in recent weeks. In this case, however, the bot left the data intact.

What data was exposed?

The Elasticsearch cluster contained 115,281 patient records, each of which included some or all of the following information:

- Full name

- DNI number (Argentina national ID number) or DNI number

- CUIL number (Argentina tax ID number)

- Gender

- Date of birth

- Photo

- Phone number

- Email address

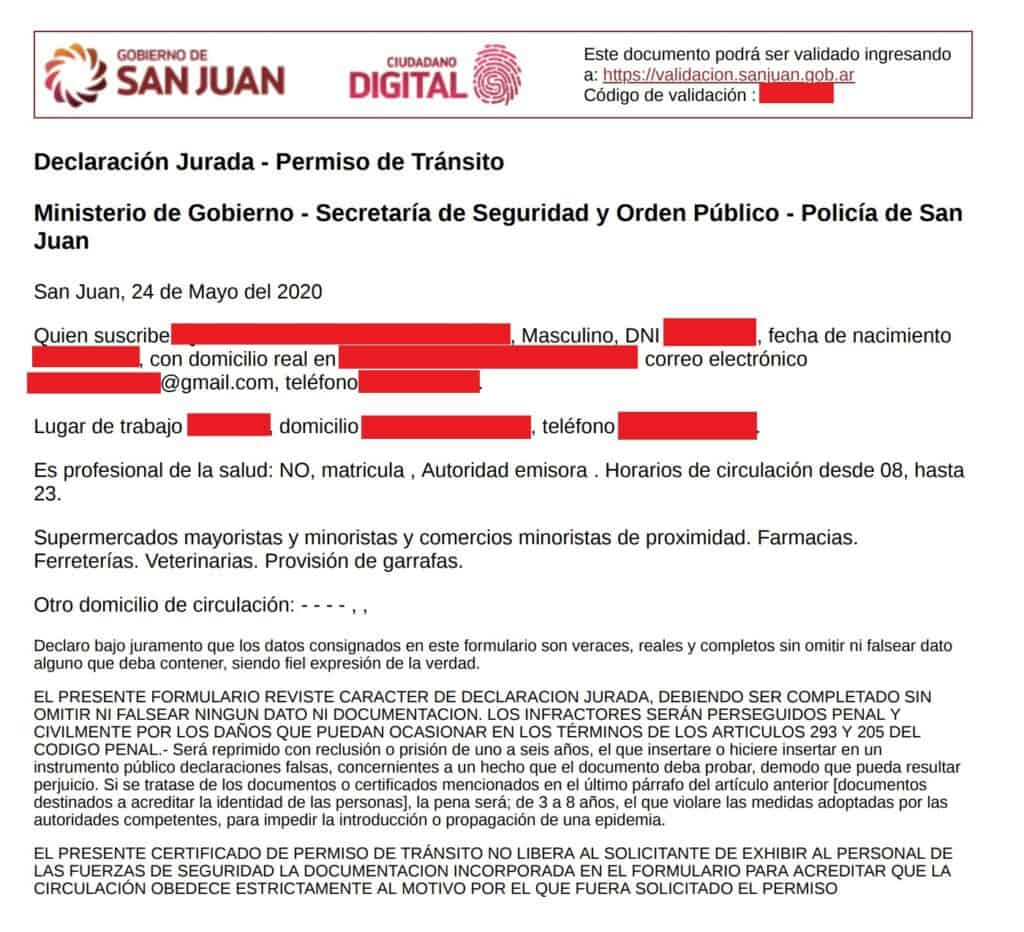

33,790 of the records contained a phone number. We were able to use the DNI, gender, and phone number to email ourselves copies of applicants’ circulation permits using the San Juan government’s online application status checker (shown in top image). Any email address works; it doesn’t have to match what’s in the database.

The permits included even more personal information, including:

- Employer

- Employer location

- Employer phone number

- A list of types of businesses where the applicant is allowed to go under quarantine restrictions

- Curfew times

- Whether or not the applicant is a medical professional

- Document validation code

We determined the data belonged to the San Juan Ministry of Health based on a cookie issued at the same IP address at the database. The cookie is labeled “certificados_covid_19_ministerio_de_salud_publica”, or, in English: “ministry of public health COVID-19 certificates. The IP address also hosted a page that looks similar to others on the San Juan government’s official website.

Dangers of exposed data

We’re not experts on Argentina, but the information contained in this exposure looks ripe for identity theft and tax fraud. The CUIL and DNI numbers in particular could be valuable to cybercriminals.

As we demonstrated, the circulation permit application system is vulnerable to abuse. Criminals could obtain permits in someone else’s name and use them to circumvent quarantine restrictions.

Applicants should also be on the lookout for targeted phishing attempts and scams. Criminals could use information in the database to craft convincing messages that trick victims into clicking on phishing links and handing over even more sensitive personal or financial information.

Argentina’s Ministry of Health falls short on privacy

Argentina’s Ministry of Health manages the country’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic. In addition to circulation permits, the Ministry also published a symptom checking app where users can enter their personal information and health status to determine whether they might be infected.

Despite just being a symptom checker, the app collects a lot of private information from users, much of which mirrors what we found in the exposed database: DNI or passport numbers, symptoms, age, email address, telephone number, and location. The app has more than 5 million downloads on Google Play alone.

Coronavirus apps and contact tracing methods have been a cause for concern among privacy advocates, and this data incident validates those concerns.

How and why we discovered this incident

Comparitech researchers routinely scan the web for unsecured databases of personal information. Upon discovering a vulnerable database, we immediately begin an investigation to determine who owns it, who might be affected, and what the potential consequences could be if a malicious attacker obtains the data.

Once we determine who is responsible for the data, we send an alert so it can be secured. After that, we publish a report like this one to raise awareness and limit harm to end users.

Previous data incident reports

Comparitech has published several data incident reports like this one, including:

- UFO VPN exposes millions of logs including user passwords

- French Civic Service exposes 1.4 million user records

- 42 million Iranian “Telegram” phone numbers and user IDs were breached

- Details of nearly 8 million UK online purchases leaked

- 250 million Microsoft customer support records were exposed online

- More than 260 million Facebook credentials were posted to a hacker forum

- Almost 3 billion email address leaked, many with corresponding passwords

- Detailed information on 188 million people was held in an unsecured database

- K12.com exposed 7 million student records

- MedicareSupplement.com made 5 million personal records publicly available

- Over 2.5 million CenturyLink customer records leaked

- Choice Hotels leaks records of 700,000 customers