An advanced persistent threat (APT) is a sophisticated, long-term and multi-staged attack, usually orchestrated by nation-state groups, or well-organized criminal enterprises. The term was initially used to describe the groups behind these attacks, but its common usage has evolved to also refer to the attack styles we see from these types of threat actors.

Most of these groups are numbered and given corresponding names. They often end up with multiple monikers, because major cybersecurity organizations often come up with their own names for APT actors.

For example, APT 1 is a Chinese threat actor that’s also known as PLA Unit 61938, Comment Crew, Byzantine Panda and a few other aliases. Another is APT 29, a Russian group called Cozy Bear, Cozy Duke, Office Monkeys and several other names. North Korean group APT 38 is often called the Lazarus Group, Guardians of Peace, or HIDDEN COBRA, among other things.

There are many more numbered and named APTs, and new ones are frequently discovered. Due to the complexity and cost of mounting APT attacks, the groups behind them generally use their advanced techniques against high-value targets such as government agencies or large enterprises. Their aims often include espionage, theft of critical data, and sabotage.

What differentiates advanced persistent threats (APTs) from other cyber threats?

Advanced persistent threats tend to be complex and many-faceted, which makes them more deliberate than the opportunistic threats that plague the digital world on a wider scale. According to a NETSCOUT report, only 16 percent of enterprise, government, or education organizations faced APTs in 2017.

This makes them one of the least common threats, although their impacts can be truly devastating. The reasons behind the smaller number of APTs, and what separates them from other attacks, include:

Targets

Would you build a fortress with 20-foot walls, armed guards and attack dogs to protect a child’s piggy bank? Of course not – it would cost you more in security than the piggy bank is worth. But what if you had to protect an entire nation’s treasury worth of gold?

The point is that to keep things safe, we need to increase the protection measures in proportion with the value or importance of whatever it is we are securing. It’s impossible to make something absolutely impenetrable – all we can do is make it hard enough to break in, that attempts to do so aren’t fiscally viable.

This applies to gold, jewelry, paintings and a range of other physical treasures. But it’s also valid in the world of information, systems and digital assets. Certain entities, such as governments and major enterprises, have extremely valuable information that many would love to steal.

But the organizations that control this data aren’t stupid (for the most part). They know the value of the information, that many parties would love to get their hands on it, and that they need to have strong protection measures in place in order to safeguard it.

But what if you still wanted this information anyway? When such robust defense mechanisms are in place, a sophisticated attack is needed to even have a hope of breaking in and stealing the data or achieving other goals. These are the scenarios that require advanced persistent threat attacks.

When data and systems aren’t protected to this degree, there’s simply no need for such an elaborate, expensive and time-consuming attack. If a cybercriminal can steal the data they are chasing with a simple phishing email, why would they go to any extra effort?

Therefore, we only really see advanced persistent threats in situations where there is extremely valuable data or systems, and when a lot of effort has gone into protecting them. This overlap of APT targets include:

- Government agencies – such as departments of defense, spy bureaus, tax departments, etc..

- Universities, colleges and research programs.

- Large enterprises and institutions – covering sectors such as finance, manufacturing, tech, arms, etc..

- Essential infrastructure – such as electric grids, transportation, nuclear programs, telecommunications, utilities, etc..

Aims

If an APT is a complicated, highly-organized and well-funded attack that’s designed to get around rigorous defenses, then the objectives of the attack need to be extremely valuable to make it worthwhile for the attacker. If they can’t get anything substantial out of such a significant commitment, why would they bother mounting the attack?

For the most part, threat actors that use APT tactics aim for valuable information or systems, including:

- Databases of personal information – Such as financial details, health records and other data that can be used in a range of crime.

- Intellectual property – Industrial espionage often involves targeting IP, plans, trade secrets, and other key information that may be useful to competitors, nation-states and other interested parties.

- Classified information, including government documents, military plans and financial records.

- Ongoing communication between high-value targets – This could involve plans, personal information that could be used in extortion, and much more.

- Sabotage – Such as taking down a website and deleting critical data.

- Hijacking a website – This can be done for reasons such as political activism, cyberterrorism, or financial gain.

In some of these situations, the main goal may simply be making money, such as in cases where attackers steal and sell databases of personal information. In other circumstances, the APT campaign may serve as a way to actively harm competitors, for nation-states to jostle for power, and as shows of force. Ultimately, APTs are techniques that allow those behind them to complete objectives that wouldn’t be possible with simpler types of cyber attacks.

Sophistication

Many of the more common threats we face are automated and behave consistently, searching for the same weaknesses to take advantage of. While they are often repurposed to penetrate new organizations and systems, they tend to lack the careful analysis, planning and orchestration that go into APTs.

As we have discussed, APTs are generally reserved for situations where simpler attacks are insufficient for meeting the goals, and something more advanced is required. APT attacks often involve spending large amounts of time investigating a target and probing for weaknesses, before developing a customized plan to surmount security measures, evade detection mechanisms and succeed in the ultimate objective.

The operatives behind APTs are highly knowledgeable, with broad sets of skills. They also leverage a variety of advanced tools and strategies in their attacks. Their sophistication includes:

- Cutting-edge surveillance and intelligence-gathering techniques.

- Mastery of both open-source and proprietary intrusion tools. These can include commercial penetration testing software, as well as software obtained from darknet marketplaces. They also often develop their own code from scratch or modify existing code as the need arrives. This tailoring can be critical for penetrating organizations with strong defenses.

- Targeting multiple points in an organization in both the initial penetration and the elevation of their attacks. One example involves gaining access by successfully spear phishing a number of key people within a company. Another is to target a range of separate internal and external systems as the threat actor ramps up its attack. Attacking from so many different points can also serve to distract security teams.

- Evading detection tools. Threat actors use obfuscation techniques and sneaky tactics like fileless malware. These help to bypass the monitoring and detection mechanisms deployed by target organizations. These often rely on signatures to recognize malicious activity, which means that attack methods that can hide signatures or have previously unseen signatures can often slip past. Remaining hidden for a long period of time is crucial in APTs, so attackers put significant effort into evasion.

As an example of the complexities involved in APTs, these attacks often involve a combination of social engineering, taking advantage of software vulnerabilities, deploying rootkits, DNS tunneling, and a wide range of other approaches. Some of the individual strategies used in an APT may not seem overly advanced, but the planning, scale and cohesion of the attack as a whole is what makes them sophisticated.

A critical part of an APT may involve the simple duping of an executive with a phishing message. Almost anyone with a bit of free time, half-way decent grammar and Google can do this. But it’s all of the other elements working together that make an attack an APT. It’s this overall sophistication that is out of reach for your garden-variety hackers.

Timeline

Many cybercriminals are only interested in easy targets, aiming to get in and out as soon as possible, without much concern over whether their attack is noticed quickly once they’ve gotten what they were after.

In contrast, APTs tend to occur over an extended period of time, because the systems they target are simply too complex and well-guarded to penetrate with simple or automated techniques. As we discussed above, they involve observation, planning and many stages before the ultimate goal is achieved.

Doing each of these steps properly takes time, especially when an attacker aims to stay undetected. After such a significant outlay of resources and effort, they have to be careful about every move they make if they want to avoid setting off any alarms and having their attack blocked.

Even once a plan has been initiated, it might involve multiple rounds of phishing emails, setting up fake websites, loading malware onto targets, elevating privileges, exfiltrating data and many other tactics before the threat actor comes close to reaching its objective.

In many situations, it makes sense for the attacker to maintain access to the victim’s systems for as long as possible. This may have been the original goal, otherwise, once all of the expensive and time-consuming legwork has been done to meet the main objective, it simply makes sense to stay in there and pick up whatever other scraps may be valuable.

Long-term monitoring can yield the attacker information on the target’s latest developments and plans, grant them access to more valuable databases, and allow them to sit in on communications between key people.

The time between an APT’s initial penetration and its discovery is known as the dwell time. The length of time a threat actor can keep its presence hidden depends on a wide variety of factors, including its own skill and the target’s defenses.

Over time, many organizations have gotten much better at discovering APTs. However, some still trail behind significantly. FireEye found in 2019 the average dwell time for internal detection was 30 days, down from 50 in 2018. This contrasts with the average dwell time for external detection, which was 141 days in 2019 and 184 the year before.

The report states that 41 percent of the compromises investigated were detected within 30 days, however an alarming 12 percent weren’t discovered until 700 days or longer had passed. While almost two years is an exceptional amount of time for an attacker to have access to a company’s network, Mandiant reported on an APT that had compromised an organization for four years and 10 months.

In certain situations, threat actors can steal incredibly valuable data or cause vast amounts of damage in minutes. Imagine the trouble an APT can cause if it retains its access, not for just one or two months, but nearly five years. With such lengthy periods of access, threat actors could steal everything a target organization has to offer, or destroy it in other ways.

Resources

The sophistication and length of time involved in advanced persistent threat attacks make them incredibly costly to mount. To start, they require large teams of highly skilled hackers. People with the experience and know-how to launch these attacks can make huge sums as penetration testers and engineers working for legitimate businesses, so the entities behind these attacks may need significant labor budgets if they want to lure them into illicit activity.

But APTs require more than just people and time. The threat actors may have to pay for offices, infrastructure, hosting and much more. The price for tools alone can be dizzying. Positive Technologies created a great rundown of just how much various elements of APT campaigns can cost, some or all of which could be part of a single, sophisticated attack plan:

- Phishing

- $300+ – Tool to create malicious files

- $2500/month – Subscription fee for a service that creates documents with malicious content

- $1,500+ – Loader source code

- $10,000 – Exploit builder

- Watering hole attack

- $10,000+ – Hacking a website and installing malware

- Zero-day vulnerabilities

- $30,000-$70,000 – Windows LPE

- $1m+ – Windows One Click RCE

- $100,000-$500,000 – Chrome RCE + LPE

- Penetration testing tools (essentially legitimate hacking tools, when used with permission)

- $30,000-$40,000/year – Black market price for Cobalt Strike

- $15,000/year – Metasploit Pro

- Remote administration tools

- $100 – Modified version of TeamViewer from the darknet

- $3,000 – Hidden VNS from the darknet

- Banking malware

- $1,750 – Smoke Bot from the darknet

- Exploits

- $10,000 – For escalating OS privileges

- $130,000 – For a tool to take advantage of a zero-day vulnerability in Adobe Acrobat

- Spying malware

- $1.6 million – FinSpy spyware framework

- Certificates

- $1,700 – Fake extended validation certificate

- Self-made tools

- $30,000-$35,000 – Customized software for entrenchment and lateral movement

Many of these prices are for high-end tools and services that haven’t been previously used en mass by hackers. This makes them more likely to be able to circumvent antivirus solutions and detection methods, leading to a greater likelihood of success.

All up, one APT attack attempt could easily run into the hundreds of thousands of dollars. Not everyone has the kind of money needed to break into government entities or enterprises, so it narrows down who can actually launch these types of attacks.

The perpetrator

While your run-of-the-mill, basement hacker may dream of pulling off a sophisticated APT attack, it’s simply out of their reach. They need a team behind them, and a significant amount of resources.

Historically, the term advanced persistent threat has mainly been used for groups linked to nation-states. Few others had the necessary financial backing, the organizational capacity and the impunity of working on behalf of their government (and thus under its protection), except those linked to nation-states.

The earliest named APTs were the Chinese state-backed groups PLA 61398 (APT 1) and PLA 61486 (APT 2). Their activities often focused on industrial espionage, targeting the likes of nuclear and aerospace firms.

Groups linked to other countries were soon named as well, including Fancy Bear (APT 28), Helix Kitten (APT 34), the Lazarus Group (APT 38), and the Equation Group. These have ties to Russia, Iran, North Korea and the USA, respectively.

While groups linked to nation-states dominate the APT scene, there are also some sophisticated threat actors that seem to act solely for financial gain and don’t appear to have state ties.

These include Silence, which has targeted banks all over the world, stealing millions of dollars. Another example is the Carbanak Group, which Kaspersky claims has stolen more than $1 billion.

Advanced persistent threat (APT) attack stages

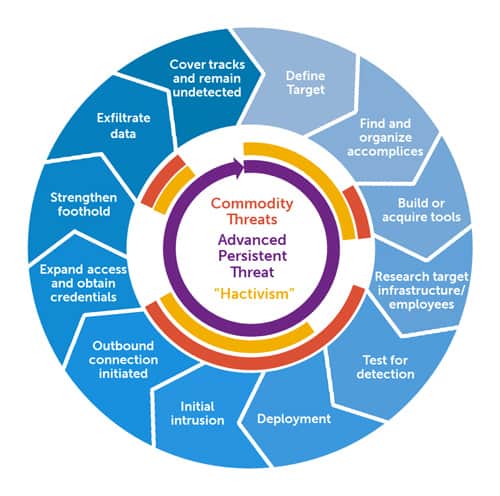

Advanced persistent threats generally follow the same patterns. Once the threat actor has chosen its target, it starts by engaging in careful reconnaissance, figuring out the best ways to penetrate the systems, expand its access, and complete its objective, all while evading detection.

The steps of an advanced persistent threat. Advanced Persistent Threat Lifecycle by Secureworks licensed under CC0.

Defining the target

The target of an APT generally depends on the nature of the group behind it. If it’s a threat actor that is solely financially motivated, the group may begin the process by scanning financial institutions, large businesses and other organizations for weaknesses that it can leverage, then choosing a target based on whichever looks easiest, has the greatest potential reward, or is the most likely to result in a hefty return on investment.

Groups linked to nation-states may be given a specific goal, such as ‘steal the plans for the next-generation aircraft, so that we can reverse engineer it,’ or ‘infiltrate the defense department and monitor the communications between high-level individuals.’ In such situations, the threat actor would have to closely examine the target, looking for even the slightest weaknesses, and figure out whichever tactics will help it succeed in the mission.

Alternatively, APTs may be given broader objectives, such as ‘sabotage critical government websites in response to the sanctions that country X has just announced against us,’ or ‘infiltrate government agencies and large enterprises and steal any information that we can use for blackmail.’

This approach gives the group a little more freedom, because they could look at several targets and then focus on whichever looked the most viable, or send out spear-phishing messages to people from a range of entities, and then target whichever are successful.

Reconnaissance, planning & testing

Once the target has been defined, the next step is to seek out information that will help in planning the attack. The more a threat actor knows about the target, its systems, defenses, detection methods, assets, employees and other key factors, the better it can plan the future stages.

If threat actors know specifics about system weaknesses, security measures, monitoring tools and even things like which employees may be disgruntled, it gives them an edge that they can use to evade detection and succeed in their objectives.

These initial investigations can involve basic research like looking through company websites, news articles, and LinkedIn pages; through to scanning the target for vulnerabilities. They could also involve inserting agents into the target organization to extract information, or flipping those who already hold key positions inside. Those with internal knowledge of an organization’s systems and weaknesses can be an extremely valuable resource at this stage.

Once the threat actor has sufficient knowledge about its target, it can begin planning its attack. It can use the information it has gathered to plot out the best ways to infiltrate the target, expand its access and complete its objective, all while remaining undetected.

The planning process can include:

- Deciding on the initial attack vector and how it will proceed toward the main aim.

- Building a team with the necessary skills.

- Setting up any required infrastructure.

- Acquiring any necessary tools, developing custom software if needed, buying zero-day vulnerabilities from other groups if necessary.

Before the attack begins, the APT will generally test its tools and techniques to make sure that they are effective. They may also attempt to circumvent the target’s detection methods to see if the various stages of their attack will be able to slip by unnoticed.

Infiltrating the target

Once a threat actor has developed a plan and laid the groundwork, it’s time for it to begin the next stages of the attack. It’s worth noting that, sometimes, the initial infiltration may not even be against the main target.

The threat actor may choose to first infiltrate suppliers, business partners or other entities close to their target, and use this access to work their way toward their overall objective.

Regardless of whether it’s the final target or an intermediary that is first attacked, the infiltration process often begins with any of the following techniques, which can give the threat actor a foothold:

- Phishing and other social engineering campaigns against key individuals to gain their credentials.

- Exploiting security vulnerabilities in networks, applications or files to plant malware on target systems. Targets will often have strong defenses in place, so the APT may need to use zero-day vulnerabilities.

- Luring employees to a website that hosts malware. If they visit the website, it can trigger malware downloads within the target’s network.

- Leaving USBs loaded with malware around the office. If an employee plugs one in out of curiosity, the USB can automatically load the malicious files.

One of the most common starting points is through spear phishing attacks that target important people within the organization. These are generally a far cry from the phishing emails you sometimes see in your spam folder.

Remember, these are expensive attacks that aim to slip by undetected. The threat actor isn’t going to blast out a poorly worded, grammatically questionable message to everyone and put the target on high alert. Instead, these phishing emails will target specific individuals whose access may be useful in further stages of the attack.

The messages are tailored to the individual, using information gained in the reconnaissance phase to make the phishing attempt far more believable. The goal is often to trick the person to hand over their credentials, and one of the most common tactics is to send them a fraudulent security alert that urges them to change their password.

When the target goes to change their password, they will be prompted to type in their details. However, they’ll really just be sending their credentials straight to the threat actor. Once the APT has the credentials for one or multiple people on hand, they have points of access through which they can infiltrate the target.

Expanding the attack

Establishing a foothold through malware or phishing is just the first step. It allows the attacker to set up a communication channel from within the target network to the command and control server, through which it can send further instructions and additional malware that elevates the attack.

After initial access, the threat actor will generally install remote access software inside the target’s network. This gives the APT a backdoor that allows it to come and go as it pleases.

At this stage, the APT will only have limited access, and still won’t be able to go where it needs to be to complete its mission. To get there, it needs to expand the attack. This involves a couple of different tactics:

- Escalating privileges – The initial infiltration may only give the threat actor low-level access. If it needs access to other specific accounts or administrator privileges, it can start by gathering whatever data is available to it, including logins and passwords. If the passwords are hashed, the attacker can attempt to crack them by brute-forcing them, or using rainbow tables. Alternatively, the APT may use exploits to obtain the higher levels of access that it needs. These techniques allow the threat actor to penetrate further into the network, slowly working its way toward the ultimate goal.

- Investigating the internal network – Once the APT has made it inside the network, it will also move laterally, collecting data and information on the surrounding infrastructure. It will take control of servers, computers and other infrastructure and collect any data that may be useful. It probes the network for more vulnerabilities, and installs other backdoors to give it easy access to various parts of the network. These tunnels also allow it to exfiltrate data as necessary, and ensure that the attacker can maintain access, even if its other entry points are closed off by the target.

Evading detection

From the earliest stages of probing a target, through to an attack’s completion, one of an APT’s primary concerns is to evade detection. If the target becomes suspicious, it may harden its security, making the penetration much more difficult. Alternatively, it may discover the threat actor in the middle of the attack and manage to put a stop to it, potentially wiping out months of work.

Attackers develop their evasion techniques by studying the network and its detection tools, then testing ways to get around them without raising the alarm. Some of the most common ways that they hide various aspects of their attack include:

- Fragmenting packets – Threat actors can transmit data packets by splicing them into packet protocols that are less suspicious, allowing them to bypass firewalls and intrusion detection systems. The packets are reconstructed after they have passed through the security mechanisms.

- Steganography – Hiding data or malware in pictures and other seemingly mundane files.

- PHP evasion – Reordering characters to embed backdoors in the code of websites or web applications.

- Examining mouse activity – By looking for clicks or other activity, malware can determine whether it has been opened in the targeted operating environment, or in virtualized systems. This can tell the malware whether it is being executed in a malware analysis system, antivirus sandbox, or by a human operator, and allows it to act accordingly.

- Obfuscating the attack origins – By hiding the origins of an attack, or making it appear as though it originates from a false location, the attacker can help to hide its identity and intentions.

- Using other attacks as smokescreens – It’s much easier for an APT to slip various parts of its attack past the target’s security team if the team is distracted by something else. Threat actors will often launch DDoS attacks and other onslaughts at their targets, purely to stop the security team from noticing what they are actually doing.

Completing the initial objective

Once an attacker has probed throughout the network and obtained the access it needs, the next step is to complete its goal. At this stage, it may damage or take over websites, destroy data, or sabotage other critical infrastructure and assets.

In many cases, the goal is data theft, so the APT will collect each of the valuable databases it identified when it explored the network, and then transfer them to a secure place inside the network. This data will typically be compressed and encrypted, ready to be exfiltrated. The data is then secretly sent to a server under the control of the APT, often while a smokescreen attack is going on to distract the security team.

Once the data has been transferred outside of the network, the target can no longer keep it out of the hands of the APT. The threat actor will generally scrub any evidence of the attack, making it more difficult for the target to detect the compromise, or determine who the attacker was. Upon completion, threat actors will often keep their access to the network, so that they can continue monitoring the target, and possibly launch new attacks in the future.

Examples of advanced persistent threats (APTs)

Advanced persistent threats are mainly aligned with nation-states, but there are some well-organized criminal groups that also have similar capabilities. There are dozens of named APTs, but we’ll stick to just a couple of nation-state examples.

While it may seem like these kinds of threats only come from countries that are perceived as adversarial to the West – Iran, China, North Korea, Russia – that isn’t exactly true. These are just the threat actors that we tend to hear about in Western media. There are also APTs in Israel, France and many other countries.

To keep things relatively balanced, we will discuss China’s PLA Unit 61398 and the US-linked Equation Group.

PLA Unit 61398

The first numbered advanced persistent threat group was PLA Unit 61398, known as APT 1 and Comment Crew, among its other monikers. The APT is linked to the Chinese Government, and in 2012, the cybersecurity company FireEye estimated that it had already attacked more than 1,000 organizations.

Its victims include those in the tech, finance, mining, telecommunications, manufacturing, shipping, arms, energy, and other industries. It also targeted critical infrastructure in the US, including waterworks and power grids. Some of its bigger name victims include Coca Cola, security firm RSA, Lockheed Martin and Telvent.

PLA Unit 61398 has been active since at least 2002. While most of its victims were from the US, its targets also included government agencies in Vietnam, South Korea, Taiwan and Canada. According to Mandiant, it often stole information on manufacturing processes, test results for clinical trials, negotiation strategies, technology blueprints, pricing documents and other proprietary information.

One example of the group’s modus operandi was discussed by the New York Times. Coca-Cola was in the midst of an acquisition bid for the China Huiyuan Juice Group, worth $2.4 billion. During the negotiation process, PLA Unit 61398 was rifling through the computers of Coca-Cola executives to try and find out the company’s strategy.

The attack started with a spear phishing attempt, which led one of Coca-Cola’s executives to click on a malicious link. This gave the group its entry point into Coca-Cola’s network. Once it was in, it managed to collect and send confidential files back to China each week, all without being noticed.

It can be complex to attribute attacks to a particular threat actor. Despite this, there is near certainty that PLA Unit 61398 is behind the Coca-Cola attack and many of the others that have been linked to it. After following the attacks for more than six years, Mandiant found that the IP addresses and other evidence pointed to the Pudong district of Shanghai, where the headquarters of the PLA Unit 61398 is located.

The firm’s report left little doubt in its conclusions about who the responsible party was. Although it did admit ‘one other unlikely possibility’:

A secret, resourced organization full of mainland Chinese speakers with direct access to Shanghai-based telecommunications infrastructure is engaged in a multi-year, enterprise scale computer espionage campaign right outside of Unit 61398’s gates, performing tasks similar to Unit 61398’s known mission.

Of course, such an idea is fanciful, and numerous others back up Mandiant’s conclusions:

- Senator Mike Rogers, former Chairman of the House Intelligence Committee stated that the Mandiant report was “completely consistent with the type of activity the Intelligence Committee has been seeing for some time.”

- The Project 2049 Institute, an NGO that focuses on Asian security and policy issues described PLA Unit 61398 as the “Third Department’s [a branch of the Chinese military responsible for monitoring foreign communications] premier entity targeting the United States and Canada, most likely focusing on political, economic, and military-related intelligence.”

Nation-states tend to be a little shy when admitting to their cyber antics, and Chinese officials initially brushed off the accusations, with statements such as, ‘‘China resolutely opposes hacking actions and has established relevant laws and regulations and taken strict law enforcement measures to defend against online hacking activities.’’

F BI — Five Chinese Military Hackers Charged with Cyber Espionage Against U.S. by the FBI licensed under CC0.

Although the Chinese Government still hasn’t admitted to any individual attacks, in 2015 it did acknowledge the existence of cyberwarfare units. Of course, this was no surprise to US authorities, who had already indicted five PLA Unit 61398 officers in relation to the attacks.

Equation Group

If you ever doubt how secretive APTs can be, look no further than the fact that the Equation Group lurked in the shadows for more than 14 years before it was publicly revealed. No, this wasn’t some small, rag-tag outfit stealing a few thousand credit card numbers at a time, it was a threat actor described by Kaspersky as surpassing “anything known in terms of complexity and sophistication of techniques.”

According to Kaspersky’s report, the group may have infected tens of thousands of victims throughout the world, having operated since at least 2001. Its targets have included government agencies and institutions, Islamic activists and scholars, companies that develop encryption technologies, telecoms, oil and gas companies, mass media, transportation infrastructure, the military, financial institutions and others.

While the security firm withheld a lot of detail to protect the victims, it did reveal just how powerful the group was. The Equation Group had access to several zero-day vulnerabilities before the threat actors behind Stuxnet and Flame.

Not only does this imply that the Equation Group collaborates with some of the most powerful hacking organizations in the world, but it also suggests that the Equation Group is superior.

As one of the premier hacking organizations, the Equation Group had a wide variety of techniques up its sleeve. Some of its more interesting tricks have included:

- Intercepting CDs sent out by organizers of a science conference and installing malware on them. When the attendees received their CDs, they presumed they were simply pictures of the conference. However, once they ran the seemingly harmless CDs on their computers, they installed the Equation Group’s DoubleFantasy implant, giving the threat actor an opening into the target’s systems.

- The Fanny worm used two zero-day exploits to map air-gapped networks, such as those in highly sensitive environments like financial and military computer systems. When an infected USB stick was plugged into an interconnected PC that had been infected by Fanny, the Equation Group could save commands on the USB’s hidden storage area. When the same USB stick was plugged back into an air-gapped computer, Fanny would execute the commands.

- The nls_933w.dll module allowed the Equation Group to reprogram hard drive firmware in more than a dozen common brands. These included Toshiba, IBM, Seagate, Maxtor and Western Digital.

The Equation Group is thought to be linked to the United States National Security Agency (NSA). More specifically, F-Secure believes that it’s associated with the agency’s Office of Tailored Access Operations (TAO), which has since been renamed Computer Network Operations.

This is because Der Spiegel published NSA excerpts that asserted the TAO had access to a tool known as IRATEMONK. Equation Group’s hard drive firmware module has many similar components, leading F-Secure to conclude the link between the two entities.

More evidence of association is the link between the Equation Group’s attacks and Stuxnet, which is widely attributed to the US. There are also timestamps analyzed by Kaspersky that imply that the group behind the attacks had Monday-to-Friday working hours that were in-line with the Eastern coast of the US. There are several other indicators of links between the two, but politics often stops cybersecurity firms from outright naming those responsible.

How can you tell if your organization is being attacked by an advanced persistent threat (APT)?

APTs are complex attacks that are carefully designed to achieve their goals without being detected. This makes it incredibly difficult to notice when these attacks are actually happening. However, there are some common occurrences that may tip you off about an APT’s presence. These include:

Sophisticated spear phishing emails

APTs often start their attacks with spear phishing emails, so an uptick of these messages may be a sign. If the spear phishing emails target employees with high-level access to your organization’s systems, it may be an even stronger indicator.

More generic phishing emails aren’t necessarily a good sign of an advanced persistent threat. If the email just says “Hey, watch this cool video!” and links you to a malicious website, your organization probably doesn’t have too much to worry about. Emails like this are too obvious and have a low chance of success, which is a big risk for an attacker that is trying to keep their penetration attempts discreet.

Instead, you should be on the lookout for more sophisticated messages. Pay extra attention to those that are individualized to the targeted recipient. If they contain internal company information that isn’t available to the public, it indicates that whoever is sending them has invested significant time and money into investigating your organization and its weaknesses. This can be a sign that an APT may be trying to penetrate your network.

You should be especially wary whenever you come across spear phishing messages addressed to systems administrators, CEOs, CISOs and other key individuals. If your organization notices messages like this, you should be on the lookout for other signs of an APT either already inside or attempting to breach your network.

Late-night logins

APTs often target far away countries that lie in different time zones. Despite this, many of the hackers involved in these campaigns work relatively normal hours in their own country. The discrepancy in time between the targeted country and the APT’s origins can lead to hackers trying to gain access at strange times, often late at night or early in the morning.

If your company begins to notice an unusual increase in login attempts at these hours, it could be another clue that an APT is trying to infiltrate your network. Of course, these same signs could just be employees working late to meet deadlines or an attacker of more modest means trying to wrangle their way in. Nonetheless, organizations should still be wary, especially if late-night logins are combined with some of the other indicators.

Trojans

APTs often install multiple Trojans in different parts of an organization’s network to make it easy to access various parts. They also use them as redundancies, just in case other forms of network access are blocked. If they only had one entry point, months of their work could be easily undone if the target’s security team comes across it.

While a single Trojan certainly doesn’t mean you are under attack from an APT – after all, most of us have probably experienced a couple when we were less internet-savvy – multiple entry points in disparate parts of your network could be yet another indicator.

Unexpected data flows & aggregates

APTs often transfer large amounts of data within a targeted network, and also externally so that they can steal it. Organizations need to look out for these unexpected flows of data, and put a stop to them if they notice anything nefarious. These large volumes of data may be traveling between clients, servers or networks, and they should be distinguishable from your organization’s baseline data transfers.

If organizations want to be able to notice these unauthorized data transfers, they need to know how their data transfers look under normal circumstances.

Before an APT steals data from your organization’s network, it often aggregates it internally into bundles. They will place gigabytes of data where it isn’t normally supposed to be in preparation for exfiltration. If you notice these large stores of data in strange places, you may have an APT on your hands.

How to defend against advanced persistent threats (APTs)

Defending against advanced persistent threats is as difficult as it gets. They are well-funded, have sophisticated skills, tremendous organizational capabilities, and the latest tools. You have to be incredibly diligent to keep your organization safe from these threats.

Like all cybersecurity defense plans, protecting your organization against an APT begins with analysis. You should take stock of your company’s assets, its current defenses, key weaknesses and the most likely targets.

You should also examine past APT incidents, particularly those in your industry and those that target organizations with similar setups to your own. Understanding some of the most common techniques and threats from the past can help you figure out a more appropriate defense system for the future.

Once you have taken stock of your company’s current situation and the most likely threats, you can begin implementing a comprehensive plan that protects against them. A lot of the most basic cybersecurity concepts are still critical for defending against these attacks.

Here’s how to defend against APTs:

- Update all software as soon as possible.

- Implement two-factor authentication everywhere. Physical tokens and authentication apps are much more secure than SMS verification.

- Use the principle of least privilege when setting up employee access. Only authorize them to access the resources they actually need for their daily tasks and no more. Increase or decrease their access as their roles change, and take away access from contractors and former employees as soon as it is no longer necessary.

- Enforce strong and unique passwords for each of your employee’s accounts. Password managers are probably the best way for your employees to securely keep track of them all.

- Implement intrusion detection systems or intrusion prevention systems.

- Securely configure your firewall.

- Run appropriate antivirus solutions.

- Keep secure backups of data off-site.

- Use a logging system that sends out alerts when it detects suspicious behavior.

- Educate your employees on the biggest threats and their roles in defending against them. One of the most important ones is to train them against social engineering attacks, including the advanced phishing scams that we mentioned in the previous section.

These basics will go a long way toward protecting your organization from less-sophisticated threats, and they will certainly hinder APTs. However, they aren’t enough to completely safeguard you from such advanced attacks.

APTs have strong OPSec abilities, and alongside techniques like previously unseen forms of malware and zero-day exploits, these threat actors can be incredibly difficult to detect and stop.

However, the traffic between their malware and command and control server tends to remain consistent. This means that one of the best ways to catch and defend against APTs is through network detection. Picking up on the network indicators from APTs requires prior threat intelligence, but by extrapolating on the characteristics and methods of known threat actors it can help to also protect against unknown threats.

Minimizing breakout time

Ultimately, organizations want to be able to detect APTs as soon as possible. The longer they linger, the more damage they can inflict, and the more the attack will end up costing your company. The length of time between when an attacker makes its network intrusion and when an attack is stopped is known as the breakout time.

Once the APT has made its way in, it moves laterally and escalates its privileges until it reaches its objective, so every moment is critical. If your organization wants to protect itself from APTs, then it needs to limit the breakout time as much as possible.

This means that it needs systems in place for early warning, such as the network detection we mentioned above, and a range of other monitoring tools. It needs to have highly trained and coordinated teams that can rapidly investigate and respond to threats as soon as they are picked up.

While it’s impossible for your organization to be 100 percent secure against APTs, comprehensive security practices, advanced detection methods and a rapid threat response team will go a long way toward reducing risks.