There is much debate as to whether Linux needs antivirus. Proponents of Linux state that its heritage as a multi-user, networked operating systems means that it was built from the ground up with superior malware defense. Others take the stance that while some operating systems can be more resistant to malware, there’s simply no such thing as a virus-resistant operating system. The second group is correct – Linux is not impervious to viruses, but does that mean you need to run an antivirus application? To answer that, we have to dig a little bit into how antivirus programs work.

How do antivirus programs work?

This may seem like a silly question, but it’s important to understand what malware and antivirus applications actually do. There are hundreds, if not thousands, of malware prevention apps on the market. If hunting and detecting malware is well understood, then why are there so many apps doing the same thing in different ways?

The truth is that there is a large population of well-funded bad guys out there that spend all their time thinking up ways to get malware onto your system.

They’ve been doing this for decades and there is now a very large pool of known attack vectors, plus a never-ending stream of new attack vectors emerging every day. It’s therefore not possible to detect every variation of attack, so antivirus apps must try to outwit the bad guys. Different vendors have different schools of thought on how best to do this, hence the many variations of antivirus that all attempt to the same job—protect your computer—but in many different ways.

Signature-based antivirus

The most common type of antivirus is signature-based. This means the antivirus program knows what previously seen attacks look like and examines your system for the tell-tale signs — called signatures — of those known attacks. This is a reactive method of antivirus protection because it requires the antivirus vendor to know what an attack looks like, which infers that the attack is already in use in “the wild”. If your machine already has this virus, then the application can remove it for you, but it may not be able to do much about the damage the malware has already caused.

The recent “Wannacry” malware attack first surfaced in hospitals in the UK. It then spread to 150 countries over the next few days.

Despite this shortcoming, signature-based antivirus is still a very important part of malware detection. Viruses do not instantly appear in all corners of the internet at once. They are deployed from some central attack location and make their way across the internet over time. Antivirus companies monitor known attack deployment locations and detect new malware early on. For that reason, machines protected by signature-based antivirus still enjoy a good degree of protection as long as the signatures are updated before the virus spreads to their neck of the woods.

Heuristic-based antivirus

To combat the shortcomings of signature-based protection, many vendors also incorporate a heuristic-based detection component into their products. Heuristics is an interesting field of study which seeks to detect programs that act like viruses, even though they may not match a known virus signature. Unlike signature-based protection, heuristics can protect a machine from a virus that nobody knows exists yet. It can detect new, unknown, viruses based on behavior that looks to be malicious, rather than requiring 100% certainty that this program is a known virus that has been seen before in the wild.

The numbers game

Bad guys write malware for a purpose. That purpose is usually to exfiltrate (steal) important data from your computer such as banking and personal information in order to steal money, or steal identities. Another very popular reason for deploying malware is to recruit your computer into a botnet that can be rented out at a later date for profit.

Botnets are roBOT NETworks that can be commanded to do something. Some malware will infect your machine quietly and lay dormant until it is summoned to work by the malware author. In the past, this was the main way in which large DDoS attacks were carried out. Now, “internet of things” devices are usually pressed into service for this type of attack.

Related: What is a botnet?

Bad guys are subject to economics just like the rest of us and therefore want to get the biggest bang for their buck. Just like every other software vendor, bad guys want to write their code once and deploy it as many times as possible in order to reap the largest possible reward. With that in mind, it makes sense to write code targeting the largest user-base possible. That usually means writing for the Windows desktop operating system because, by pretty much all measurements, Windows is the most popular operating system in use today.

Another very attractive platform is the mobile platform, which essentially means Apple’s iOS and Alphabet’s Android mobile operating systems. Of those two, Android has been known to be deployed with malware directly into its operating system by malicious vendors such as Blu, ZTE, and Huawei.. In addition, the Google Play Store, which is the only official place to get apps for the Android platform, is routinely discovered to have malware apps masquerading as legitimate programs in it. The Apple App Store fares a little better due to more rigorous gate-keeping, but it is not impervious to malware either.

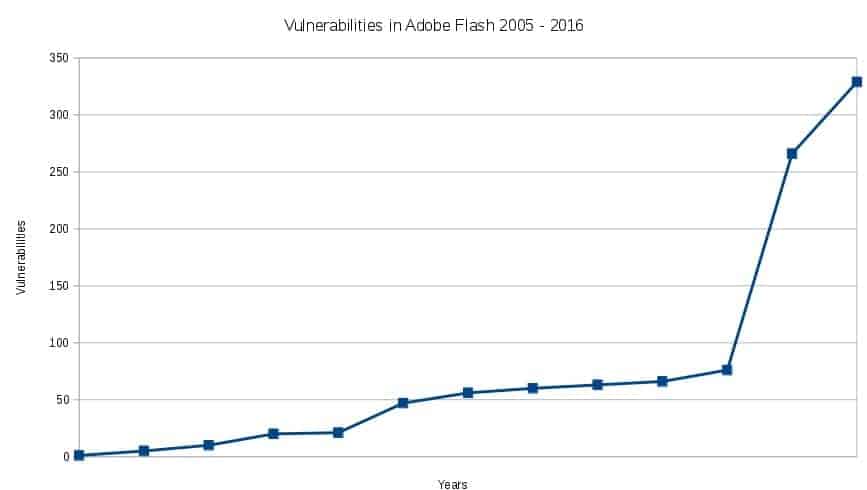

A third lucrative attack vector is software that runs on all operating systems because that allows malware authors to potentially infect every computer. These types of cross-platform viruses are generally aimed at browsers and operating system-agnostic technologies such as Java. Adobe Flash is an excellent example of a cross-platform application that is attacked relentlessly and simply cannot defend itself properly. Given its inability to fend off very serious remote execution attacks, allowing Flash to run in your browser is basically a negligent security stance.

Based on this information, if I were a malware author I would write my malware to target these platforms in this priority:

- Microsoft Windows

- Android

- Flash

Why you need antivirus on your Linux machines

If a malware author is going to follow the priorities I listed in the previous section, why does a Linux user have to worry about antivirus at all? Linux is not even on the priority list and it has an absolutely abysmal desktop market share. Who would bother to write a virus targeting Linux?

Just because Linux systems have a lower risk of malware infection does not mean there is no risk. Bad guys will try to infect all computers and only have to win sometimes. Defenders have to win every time.

At face value, there’s merit to that argument, but in fact, all three top-priority operating systems are tied to Linux. In industry, one of the main uses of Linux is to act as a file server or mail server for a large population of desktop Windows users. Therefore, deploying a Windows virus onto a Linux file or mail server is a good attack vector to get at the connected Windows desktops. Android is Linux, it’s just been modified to run on mobile devices rather than desktops, but the basic Linux-ness of it survives and the relatively lax gate-keeping of the Google Play store makes it an attractive target. Flash runs in browsers and is therefore cross-platform. An exploit or malware in Flash has an equal chance of affecting all operating systems, Linux included.

Even if you chose not to pay attention to the peripheral relationships here, it’s hard to ignore that there is indeed a fair amount of malware targeted specifically at Linux.

Lastly, some highly respected antivirus programs for Linux are free, both as in “no cost” and as in “open source”. There’s simply no reason to not install antivirus on your Linux desktop other than hubris.

Where do you get Linux antivirus?

In The ultimate guide to desktop Linux security, I write about this very topic. The best choice for any Linux application is one that is available in that distribution’s application repository. While your distro’s repository may not have the most current version of an application, the application has at least been vetted and possibly modified to run properly on your system. Sometimes that stability is worth the loss of a version or two. In the case of malware, keeping the virus signatures up to date is usually a bigger concern than the version of the antivirus application itself.

ClamAV is a mature and well-supported antivirus solution for both Linux desktops and servers. Both Ubuntu and Fedora—the two main Debian and RPM based distros, respectively—have a nice graphical front end for ClamAV that makes it easy to use.

A quick look at the Ubuntu repositories shows there are also many antivirus programs and ClamAV plugins that help protect mail servers, web servers, and compressed files. In addition, ClamAV can detect viruses in cross-platform file types such as PDF, Flash, and file archives such as ZIP and RAR, as well as Unix-based ELF executable files.

I’ve written fairly detailed instructions on how to install and configure ClamAV for Ubuntu here.

Other antivirus programs are available for Linux. F-Prot, Comodo, and Avast all provide desktop Linux antivirus programs as well. I’m not aware of any reason to choose a commercial antivirus over an easily available open source one, but everyone’s situation is slightly different so you may want to consider the feature set of each and make your own decision.

Image: TuxDroid by Sunny Ripert licenced CC BY-SA 2.0